Starting and ending point: Orikum

Days 1-2: In previous post

Day 3: Butrint Archaeological Park, Ksamil (for the beach), and the Sarandë Blue Eye. Drove to Gjirokaster in the evening (overnight in Gjirokaster)

Day 4: Gjirokaster (second overnight in Gjirokaster)

Days 5 and 6: Berat (overnight two nights)

Day 7: Tirana (overnight one night)

Day 8: Kruje, Shkodër (overnight in Shkodër)

Day 9: Shkodër (this was supposed to have been Theth National Park – it wasn’t) (overnight in Shkodër)

Days 10, 11: Valbonë a.k.a. Valbona (overnight on day 10). Returned to Shkodër and drove to Golem (overnight in Golem)

Day 12: Return to Orikum by 8:00 a.m. to return rental car (we aren’t counting this day in our road trip)

Today’s post covers day three.

Day three consisted of Butrint Archaeoloigcal Park, Pulëbardha Beach (near Ksamil), a quick stop at the Sarandë Blue Eye, and a drive to Gjorikaster to spend the night.

The Google navigation lady took us to Butrint from a direction that proved to be advantageous. It took us first to a Venetian Castle. It is possible we would have skipped it entirely had it not been the first stop. Well, that and the fact that the small ferry that only carries four cars at a time across the lake to Butrint was already full when we got there. Michael suggested that we see the castle first.

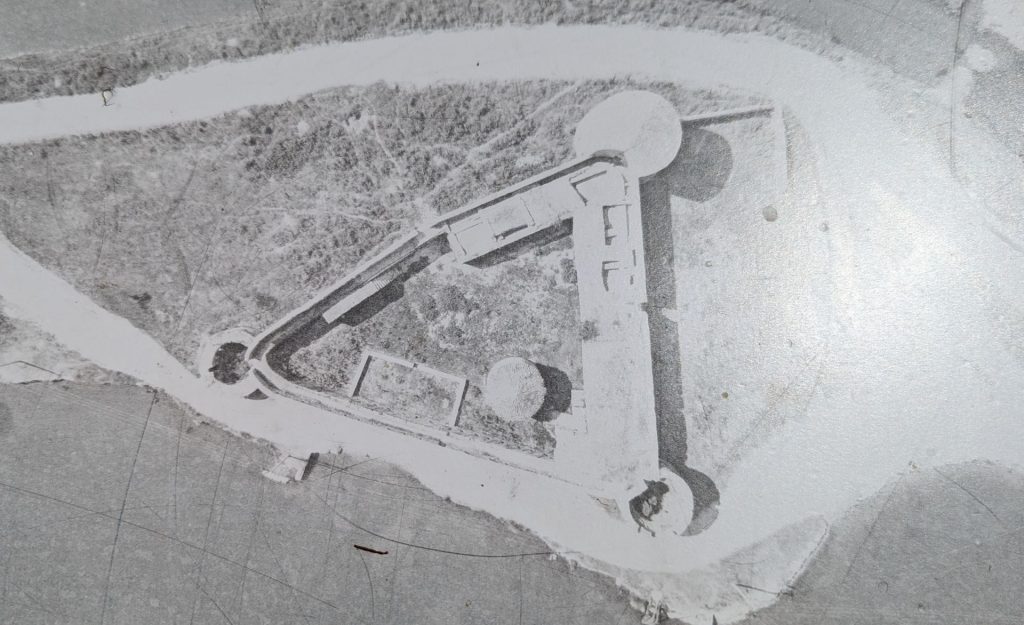

If you read farther up in this blog post, you will see a reference to Porto Palermo having “the same triangular plan with round towers found on the Venetian fort at Butrint.” This is the fort to which they are referring. This is a picture of the Venetian Castle (or fort) at Butrint from above. Look familiar?

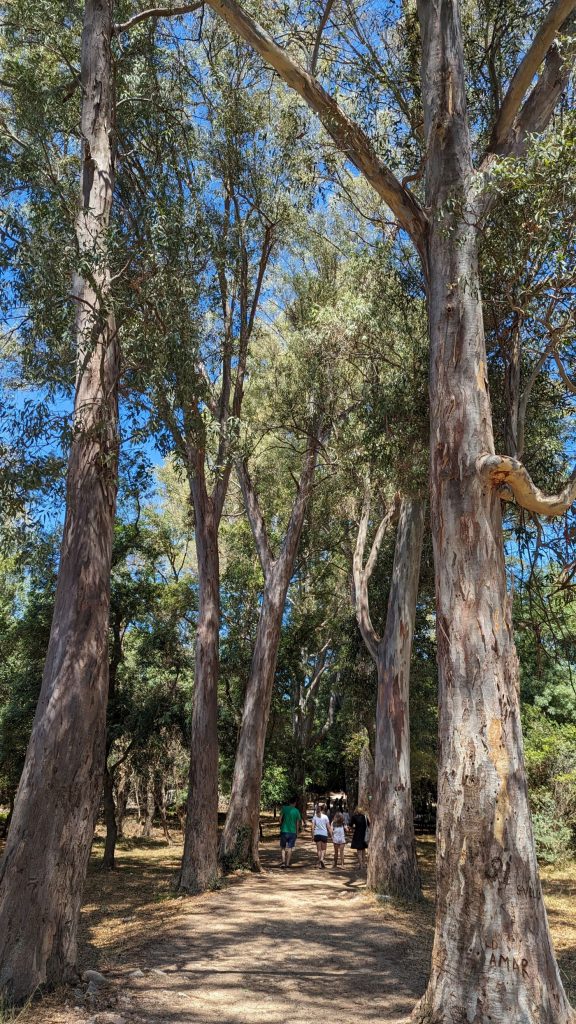

And here are the pictures we took from inside the walls:

And now it was time to take the long ferry ride (about 60 seconds) across the lake to Butrint.

You know the drill: history first.

Butrint’s name (originally Buthrotum in Latin) was derived from the word buthrotos, which means “wounded bull.” This is based on a Greek mythological legend, in which the offering of a bull failed on the island of Corfu. The bull escaped and swam to the mainland, which was considered a sign of the gods and the Greek decided to build a settlement at this place.

According to classical mythology, the ancient city known as Buthrotum, was founded by the exiles who left the city after the fall of Troy. In the epic poem “Aeneid,” the Latin poet Virgil narrates to Aeneas, who visited Butrint on his way to Italy.

Mythology aside, Butrint was an ancient port city. The old city and its heritage retain a unique testimony of Hellenistic, Roman, Byzantine, Venetian, and Ottoman cultures and civilizations. Most of the monuments tourists can visit today were discovered by the Italian Archaeological Mission, guided by Luigi Maria Ugolini, who worked in Butrint from 1928 to 1939.

The property is a microcosm of Mediterranean history, with occupation dating from 50,000 B.C., at its earliest evidence, up to the 19th century A.D. Prehistoric sites have been identified within the nucleus of Butrint, the small hill surrounded by the waters of Lake Butrint and Vivari Channel, as well as in its wider territory.

In the 4th century B.C. a chapel sanctuary dedicated to Asclepius, god of medicine, was built on the southern slope of the Acropolis hill. This was enabled by donations of religionists to the chapel. Worshippers came to the Sanctuary in order to be healed, leaving symbolic objects and money to the god and his attendant priests. The Sanctuary was the making of Butrint, and the sacred powers of Butrint’s water were to be revered as long as the town lasted. As the Sanctuary grew in fame a circuit wall of finely hewn stone blocks, fitted together without mortar, was constructed around the 10 hectare site in order to protect it.

From 800 B.C. until the arrival of the Romans, Butrint was influenced by Greek culture, bearing elements of a “polis” and being settled by Chaonian tribes. The fortifications bear testimony to the different stages of their construction from the time of the Greek colony until the Middle Ages.

In 228 B.C. Butrint fell under Roman Rule. Julius Caesar arrived in 44 B.C. and recognized its potential as a town. He designated Butrint a Roman city: Colonia Iulia Buthrotum. Augustus further developed the colony after defeating Anthony and Cleopatra at nearby Actium in 31 B.C. Augustua, his family, and private sponsors funded a major building program. The city expanded on reclaimed marshland, primarily to the south across the Vivari Channel, where an aqueduct was built. The developments included temples, forums, a theater arranged according to the Roman style, fountains, baths (thermae), an villas (private residences).

In the 5th century A.D. Butrint became an Episcopal center; it was fortified and substantial early Christian structures were built. The city retains evidence of this early Christian art and agriculture such as the large baptistery and basilica. The major ruin from the paleo-Christian era is the baptistery, an ancient Roman monument adapted to the cultural needs of Christianity. Its floor has a beautiful mosaic decoration. The baptistery’s ruins are sufficiently well preserved to permit analysis of the structure (three naves with a transept and an exterior polygonal apse). After a period of abandonment, Butrint was reconstructed under Byzantine control in the 9th century.

Butrint and its territory came under Angevin and then Venetian control in the 14th century. Several attacks by despots of Epirus and then later by Ottomans led to the strengthening and extension of the defensive works of Butrint. In 1807, a new fortress was added to the defensive system of Butrint at the mouth of the Vivari Channel. It was built by Ali Pasha, an Albanian Ottoman ruler who controlled Butrint and the area until its final abandonment.

The ancient city became a “World Heritage” of UNESCO in 1992. It is located within the National Park of Butrint. The park has a total area of 9424.04 hectares and counts about 800 kinds of plants, among which 16 are considered as endangered and 12 as rare. In the wetland complex of Butrint, there have been identified up to 246 species of birds, 105 species of fish, and 39 species of mammals, among them, many species of special conservation status.

Okay, for those who don’t like history, that was probably as dry and boring as it gets. But I hope those who like history appreciate it. 🙂

Picture time!

A measure of Butrint’s prosperity in the mid Roman period can be seen in its townscape. The plan of the new Roman town was very different to the earlier 10 ha. fortified site associated with the Sanctuary of Asclepius. The new town was laid out using a regular system of streets which divided the town into insulae (equal-size units of land within the urban area).

The excavated area in the following picture is part of one insula. The building forms a suite of rooms with mosaic pavements separated from a stone-paved courtyard by a large fountain. Its exact function is unknown but it might have been a gymnasium or possibly a private house. It was modified and re-built over four centuries and was finally converted into a church (constructed around the fountain) with a cloister located in the original courtyard in the Late Roman period.

The picture seen below is of the “Gateway to Butrint.” This was the main entrance into Butrint between the 3rd century B.C. and the 14th century A.D. In the later 3rd century B.C. an imposing entrance, the Tower Gate was constructed. It was flanked by a round tower on one side and a rectangular tower on the other, both with arrow slits. Wooden gates sealed each end of the long passageway between the two towers, which was wide enough for a cart to pass.

In the Roman period a bridge and aqueduct were constructed and crossed the Vivari Channel at this point. The water would have been distributed within the city by branch aqueducts, although none survive today.

Between the Tower Gate and the bridge lay two monumental fountains forming a symbolic gateway into the city. Only one fountain survives. Statues of Dionysius and Apollo were found in two of the three niches.

By the medieval period the bridge and aqueduct had long since collapsed Nevertheless the “Water Gate” built here in the 13th century shows how the gate remained Butrint’s most important entrance.

We walked the .6 mile back to the car and took off for the beach. We were heading to Ksamil – that’s all we knew. We didn’t know which beach we would visit. The first try was an epic fail. Waaaaaaay too busy. So we went to Pulëbardha Beach, which is a bit out of town. This is a pebble beach. It had wonderful surf!! Of course it was beautiful.

We stayed here for quite some time. The only plans left in our day were to see the Blue Eye and drive to Gjirokaster (the latter just to get to the hotel before it was too late). Since we didn’t feel rushed, we maybe stayed a tad longer than ideal in terms of seeing the Blue Eye.

We figured we would just drive to the Blue Eye, look at it, and leave. What we didn’t know is that there is a 1.2 mile walk from the parking lot to the Blue Eye. (This is why I was saying we stayed a tad too long at the beach.) The Blue Eye was pretty, but I think it would have been a bit more awe-inspiring if the sun had been shining on it.

I suppose I should tell you what the Blue Eye is. There are two in Albania. We were looking at the Sarandë Blue Eye. There is another one in Theth National Park. The Sarandë Blue Eye is a water spring and initial water source of the Bistricë, a 25 km long river which ends in the Ionian Seat just south of Sarandë. The source is a natural phenomenon with a depth of at least 50 meters, the deepest any diver has been able to go, so the actual depth is unknown. The dark center of the cave creates the deep blue color of the eye. The spring pumps water from the cave at high pressure, creating this wonder of Albanian nature.

One quick word about Hotel Fantasy and then I am going to end this blog. I will share more of our trip in other posts.

We liked Hotel Fantasy a lot. We were a bit confused when the Google Navigation Lady took us to a parking garage instead of a hotel, though. I talked to a guy on the street and he pointed across the way to Hotel Fantasy and indicated that the parking ramp was definitely the place to go. You gotta walk to the hotel from there. Thus began our adventure in Gjirokaster, to be shared next time.