Days 1-6: In previous posts

Day 7: Tirana (overnight one night)

Day 8: Kruje, Shkodër (overnight in Shkodër)

Day 9: Shkodër (this was supposed to have been Theth National Park – it wasn’t) (overnight in Shkodër)

Days 10, 11: Valbonë a.k.a. Valbona (overnight on day 10). Returned to Shkodër and drove to Golem (overnight in Golem)

Day 12: Return to Orikum by 8:00 a.m. to return rental car (we aren’t counting this day in our road trip)

Today’s post covers day seven.

Do you remember the story we told about losing the shift handle for our dinghy’s outboard motor? We have not been able to find a new handle anywhere. We’ve even looked for something other than an actual handle that we could use as a proxy. Well, Michael Googled “outboard motor” in Durrës and found a store. We decided that this was the day to go there since: 1) they would be open, 2) it was close to our next actual designation (Tirana), and 3) it was the only place we’d found when Googling outboard motors.

Durrës is both a big city and a tourist destination. It apparently has super good beaches. That meant that traffic was crazy! Plus, the Google Navigation Lady kept telling us to go the wrong way on a one-way street to get to the store. So I dropped Michael off on a street corner so he could walk to the store and I drove around. It took me at least five minutes of ignoring the Google Navigation Lady’s bad directions before I got near the store. By that time, Michael had found out that they didn’t have a handle, but the guy who worked there suggested a store that might. We went to that store and struck copper. (Not gold, but copper.) This is what we bought:

We also bought a metric tape measure and some gloves that will protect my hands when managing “slime lines” (mooring lines). We had to use the head while we were there. We see this type from time to time. I think I first saw one when I was in my twenties. I remember wondering how I was supposed to use it. 🙂

Having sort of successfully completed our shopping spree, we gladly left the congested traffic of Durrës behind and headed to Tirana. We’d read that one should try to avoid driving in Tirana, so we stayed in the Granda Hotel, a bit away from the town center. I will say that I don’t think the traffic was worse than any other I’ve driven in before or during this trip, but it was nice not to manage it and try to find a parking space (the latter can be problematic in the tourist spots).

We had wanted to spend an entire day in Tirana – the capital of Albania – but our shopping spree and the detour ate up nearly two hours. That meant we didn’t have time to do all that we wanted to do. We had to skip Bunk’Art 2 and the Natural History museum (I am including these since you will want to visit them if you go to Tirana), but we went to Bunt’Art 1 and rode the Dajti Ekspres.

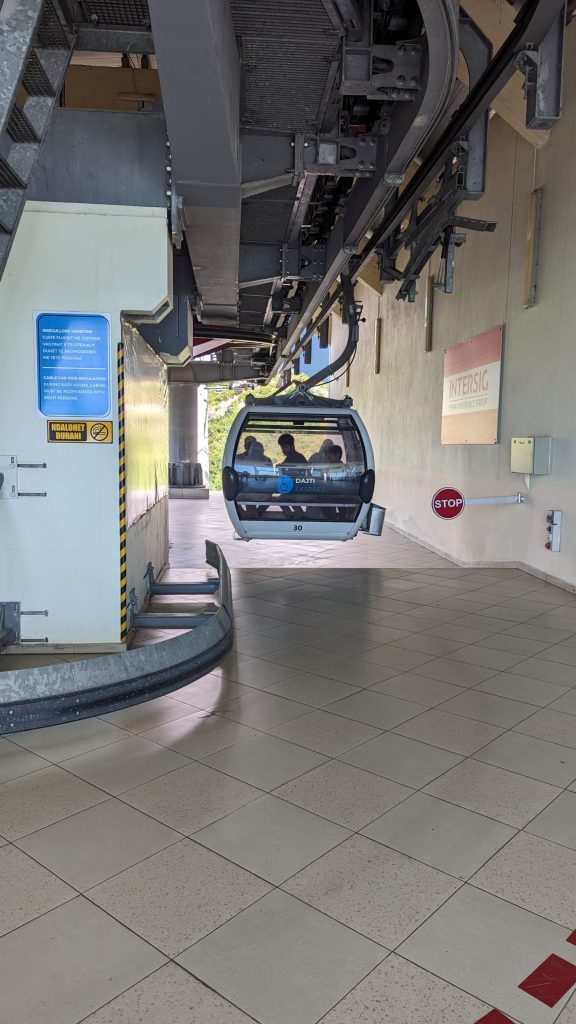

We rode the Dajti Ekspres first. (I should note that “ks” in Albania – and elsewhere we’ve been – is the usual spelling for what we think of as the “x” sound. We occasionally see an “x” – as in “taxi” instead of “taksi,” but “ks” is more ubiquitous.) Anywho, The Dajti Ekspres ascends more than 800 meters from the city center to Mount Dajti. The one-kilometer-long ride takes about 15 minutes, making this the longest cable car ride in the Balkans. The views are absolutely spectacular. I took lots and lots of pictures but will try to limit the number I share for your sake. Ride it with us!

And what did we do at the top? Exactly what you’d expect! We played mini-golf!

It was a fun 18-hole course. I know you want to know who won. I did. 🙂

It was time for Bunk’Art 1, which is conveniently located just around the corner from the lower Dajti Ekspres station.

As noted above, there are two Bunk’Art museums: Bunk’Art 1 and Bunk’Art 2. Bunk’Art 1 (which we visited) focuses more on the general history regarding Albania’s communist past, while Bunk’Art 2 takes a closer look at the different institutions used by the regime to spy, persecute, and control its own people. Described by another source, Bunk’Art 2 is “reflects Tirana’s initiative to use culture to celebrate the birth of a new era, whilst remembering its solemn past.”

Here is some more background information about Bunk’Art 1:

In November 1944, the Nazi occupation of Albania ended. However, instead of breaking the cycle of suffering, the victorious National Liberation Movement (NLC), led by Enver Hoxha, turned into the evil they vowed to vanquish. In a sick twist of fate, the liberator had become the oppressor.

The NLC, also translated as National Liberation Front, was an Albanian communist resistance organization that fought in World War II. It was created on 16 September 1942, in a conference held in Pezë, a village near Tirana. In May 1944, the Albanian NLC was transformed into the government of Albania and its leaders became government members, and in August 1945, it was replaced by the Democratic Front. The Albanian National Liberation Army was the army created by the National Liberation Movement.

Enver Hoxha: When Nikita Khrushchev became the most powerful man of the Soviet Union in 1961, Enver Hoxha, the communist dictator who ruled Albania from 1944 until his death in 1985, was furious. Labeling the nascent de-Stalinization process as outright treachery against the communist ideals, all ties between the countries were cut immediately, leaving Albania completely isolated on the international stage (Albania turned to China for a decade but the story repeated itself after Nixon’s visit to the country in 1972).

Over the following decades, Enver Hoxha and his communist comrades went on to establish one of the most horrific dictatorships in post-war Europe. Any resistance was brutally quenched, human rights replaced by torture, abuse, and murder. Those who were deemed “enemies of the state” either slaved away in the labor camps and mines or carved out a miserable existence in the darkness of a cell.

At the same time, the country was transformed into a fortress. A fortress no one should be able to enter nor leave. Isolated from the world, fear and paranoia reigned within the hearts of the Albanian people.

To compensate for the sudden lack of allies, Hoxha ordered the “bunkerisation” of the country. In his paranoid mind thousands of bunkers should transform his homeland into an impenetrable fortress able to withstand an imminent onslaught from all sides. Soon, Albania’s coast and countryside were littered with concrete domes, while her mountains were penetrated and permeated by underground fortifications.

The most impressive of these subterranean shelters was built in the 1970s at the outskirts of the country’s capital Tirana. The complex, designed to survive a nuclear attack, was constructed to guarantee the smooth function of the political and military leadership in time of crisis and featured an assembly hall for the parliament and over 100 offices across five floors, including Enver Hoxha’s personal apartment. The bunker was for the political elites only. Therefore, the bunker remained secret for much of its existence. Hoxha died before the bunker was complete and the bunker was never actually used. This former shelter is now Bunk’Art 1, a museum and art center.

Bunk’Art 1 contains hundreds (thousands?) of documents and pictures, a plethora of historical information, and sound effects that make the experience more eerie and “real.” It is overwhelming. We were there for about an hour and a half and would have stayed longer had they not been closing. We had to speed-walk through the end. Two hours is a better time allotment. I have chosen a handful of things to share with you. I can’t say that they are the most important or even the most interesting things we saw because we were – and still are – on information overload. But here they are, for what they are worth. We strongly encourage you to visit this yourself if you find yourself in Tirana, Albania.

The first room you encounter is the decontamination room. It was to be used by everyone who came from outside who could be contaminated by chemical weapons or radioactivity. In the same room, above in the right is a handle which blocks outside air from getting into the bunker.

The supreme commander of the armed forces during the time when the bunker was built (1972-1978) was, as you know by now, Enver Hoxha. His office was the biggest and most luxurious one inside the bunker and was meant for him and his wife. The office is composed of an anteroom where his personal secretary stood, a working office, a bedroom, and a bathroom. This room, the one dedicated to the Prime Minister, and the one for the chief of staff were the only rooms with carpet. Only this room has fiber walls (which were considered expensively huge when this was built).

Enver Hoxha never slept in this room even though he participated in two military drills after the official inauguration of the bunker on June 24, 1978.

Office. There is a seating area to the left of this.

This gray container, located in Hoxha’s office, is a mobile system for oxygen production. It was present in every room in case of a long stay in the bunker. Inside of the canister are five “tabs” that contained a chemical substance which on contact with the air released oxygen. The “tabs” were stored in a sealed metal case which completed the kit. The military had to handle the “tabs” using gloves, which suggests that this system would offer no real guarantees of healthfulness. These units were produced in China.

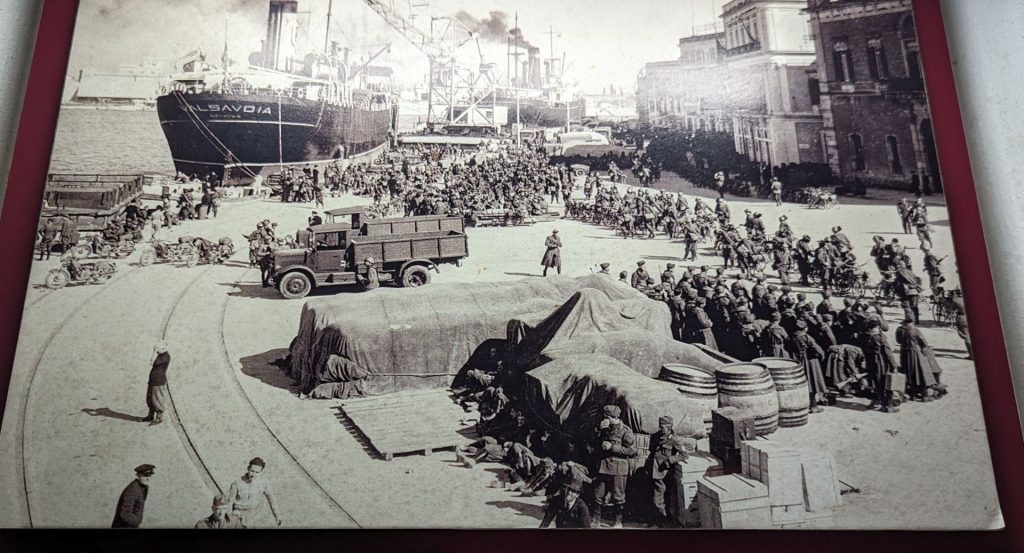

As Germany annexed Austria and moved against Czechoslovakia, Italy saw itself becoming a second-rate member of the Axis. After Hitler invaded Czechoslovakia without notifying Mussolini in advance, the Italian dictator decided in early 1939 to proceed with his own annexation of Albania. Thus, World War II began in Albania. Hence this picture in Bunk’Art 1.

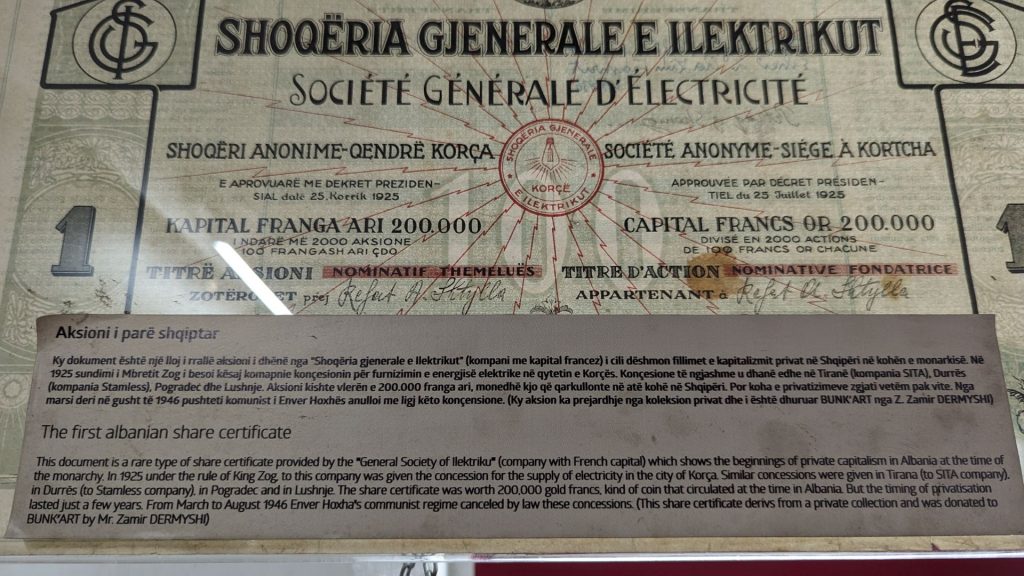

This is what the small print beneath this document says:

“This document is a rare type of share certificate provided by the “General Society of Ilektriku” (company with French capital) which shows the beginnings of private capitalism in Albania at the time of the monarchy. In 1925, under the rule of King Zog, to this company was given the concession for the supply of electricity in the city of Korça. Similar concessions were given in Tirana (to SITA company), in Durrës (to Stamless company), in Pogradec and in Lushnje. The share certificate was worth 200,000 gold francs, the kind of coin that circulated at the time in Albania. But the timing of privatisation lasted just a few years. From March to August 1946 Enver Hoxha’s communist regime canceled by law these concessions. (This share certificate derives from a private collection and was donated to BUNK’ART by Mr. Zamir DERMYSHI)

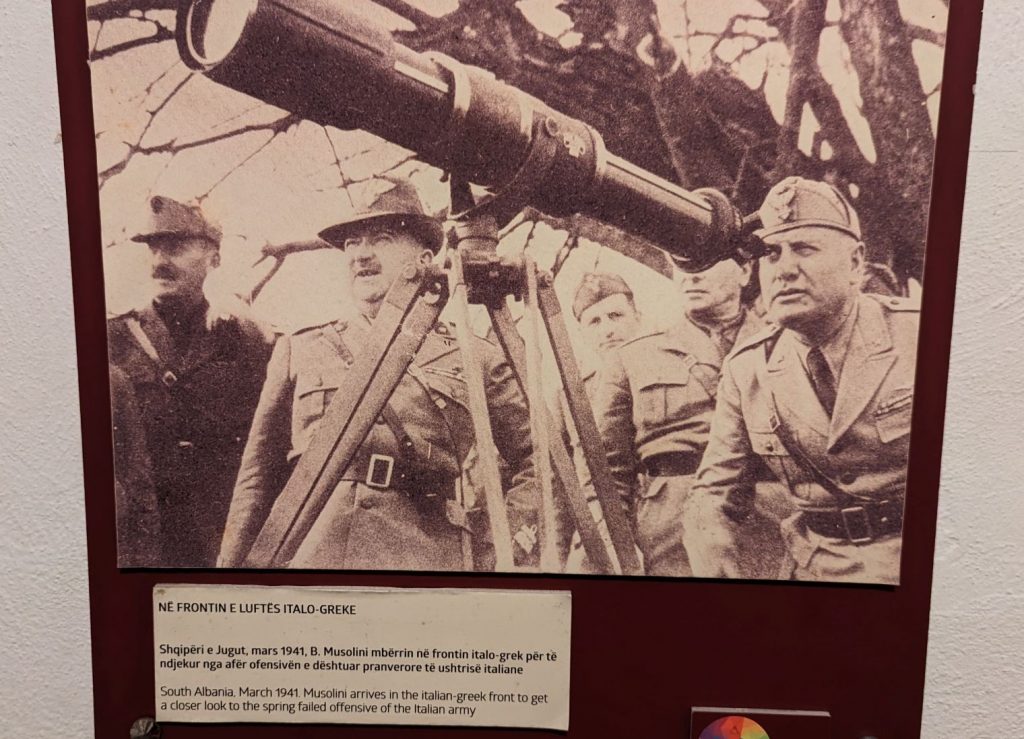

Next up: Background for the Mussolini picture

Hill 731 was the scene of the most ferocious battle of the Greek-Italian War in Albania. Watched by Mussolini himself, on March 9, 1941, the Italians launched their Spring Offensive, designed to stem four months of humiliating reverses. The objective was a pair of parallel valleys dominated by the Greek-held Hill 731 that had to be taken at all costs.

For 17 days, after a massive artillery barrage, the Italians threw themselves with great courage against the Evzones on the hill, to be repeatedly smashed with appalling losses. It was an Iwo Jima-type merciless fight at close quarters, but the battered Greeks held.

Mussolini had wanted a spring victory to impress the Führer. Instead, the bloody debacle of Hill 731 could well have contributed to Hitler’s decision to postpone his invasion of Russia by at least four weeks, a costly delay.

I had not heard this next story. It is tragic and true and I plan to tell it in some detail. This is the story of Kostaq Stefa, the hero of 30 Americans, who was a martyr of democracy. Here’s what happened:

November 8, 1943. War raged on the Italian peninsula. An American transport plane set out from Sicily for Bari, Italy. The sky was sunny and clear on take off. The plane carried an Army medical air evacuation team of 13 nurses and 13 medics and a flight crew of four men. The youngest medic was 19 and the oldest was 36. The nurses ranged in age from 23 to 33 years old. They were all part of the 807th Medical Air Evacuation Transport Squadron. The medical team had been ordered to Bari to attend to a growing population of wounded GIs. But the weather changed that day, and fierce storms over eastern Italy and the Adriatic blew the flight off course and forced a crash landing that left the Americans stranded for months in Nazi-occupied Albania.

Kostaq Stefa, a patriot and intellectual from Berat, was 39 years old when the partisan command entrusted him with the task of leading the Americans on a long and dangerous journey to the southern coast of Vlora, Albania from where they had to depart for Italy. Kostaq Stefa’s family sheltered, fed and protected three of the 13 nurses, while the rest of the survivors had been sheltered by other residents of Berat. The Americans were lucky that so many of the Albanian people risked their own lives by giving them food and shelter. There were days when the Americans only had a bite of cornbread, so every little bit helped. If the villagers had been caught helping the Americans, the village likely would have been burned and many of its residents killed.

The arrival of German patrols in search of them forced the Americans to leave as soon as possible and Kostaq was put in charge of the group. Kostaq knew English very well after studying at the American Harry Fultz Technical School in Tirana, where he later taught. The first Albania boy scout organization was created in the school, and Kostaq was nominated as its president. Because of his language and skills as an explorer, partisan commanders entrusted him with the lives of 30 Americans, who at the time were allies in the fight against the Nazi occupiers.

The journey through the snowy mountains lasted 63 days. On January 30, 1944, Kostaq finally returned home, after three months away. The first 27 Americans had already escaped and were in Italy.

On November 17, 1944, the Germans withdrew from Tirana, and on November 28, the first communist government led by Enver Hoxha was formed. The first “special” trials started in Tirana. Hundreds of Albanians were arrested by the communists on charges of collaborating with the Germans or the National Front and many were sentenced to death. Kostaq felt that he was far away from these reprisals, not only because he had never had any contact with the Nazis, but also because he had offered his help to the partisans by rescuing 30 American allies. But he was mistaken.

He was arrested on September 8, 1947, because of his relations with the Americans and the Harry Fultz school, which the communists already considered a “conspiracy center.” After being tortured for three months, the investigator in charge of his case explained that Kostaq, “had conspired with the Anglo-American enemy together with other students of the Harry Fultz school by organizing clandestine meetings in his house in which Harry Fultz himself had participated.” A totally fabricated allegation. A trial took place behind closed doors in January 1948 by a military court, without the presence of a defense lawyer, and there he was sentenced to death.

It is too late to make a long story short, but there is one more cruel piece to this story. Kostaq’s wife was told that his death sentence had been converted to a sentence of 101 years of imprisonment. She was allowed to visit Kostaq for four minutes before he was to be transferred to Burrel to serve his time, during which time Kostaq asked about their five children and asked his wife to, “Promise me that you will always dedicate yourself to their teaching.”

The next morning, Alfredo, Kostaq’s 14-year-old eldest son, happy for his father whose life had been spared, asked permission at school to take a packet of sweets to the prison guards and ask at what time his father would be transferred to Burrel. The guard took the sweets from his hands and without any sign of regret told him: “Do you have these for Kostaq Stefa? Long live the Party, because he was killed by firing squad this morning.” It was March 4, 1948.

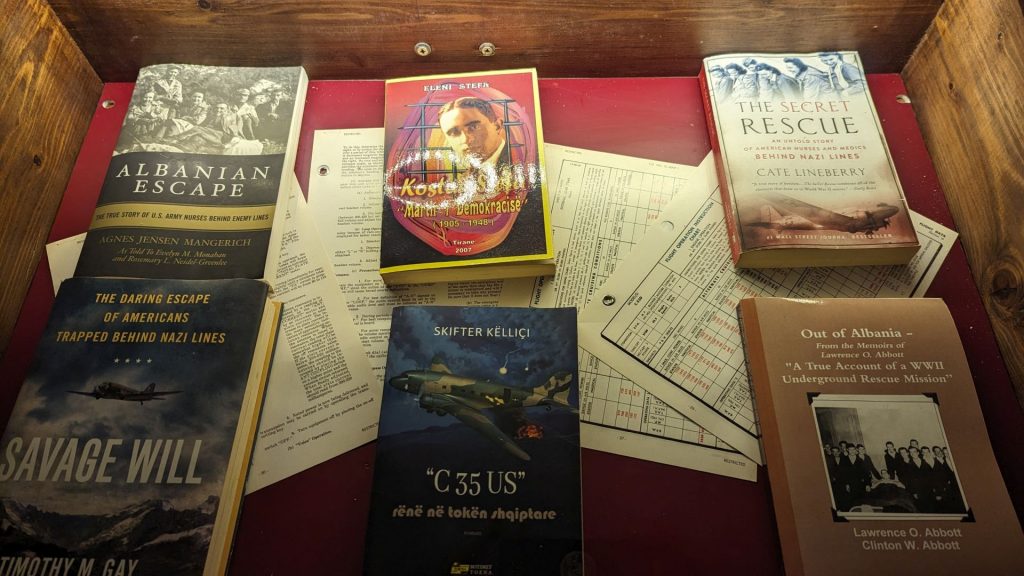

This extraordinary story of 13 American nurses and 13 American medics rescued by the Albanian people in the middle of the Second World War, was covered by military secret until 1992, the year of the fall of the communist regime in Albania.

I read a piece by Robin Lindley, who interviewed Cate Lineberry, author of The Secret Rescue: The Untold Story of American Nurses and Medics Behind Nazi Lines (Little, Brown and Company). She had interviewed the children of the Americans to gather information for her book. She was able to track down the families of almost all of the Americans. In the interview, Ms. Lineberry said, “Some of the children knew a little bit of their parents’ stories but several expressed the wish that they had asked more questions while their parents were alive. Some of them only knew that their father or mother had been in Albania briefly. A few asked more questions of their parents after Agnes Jensen Mangerich’s book came out in the 1990s.

But most of [the children of the Americans] didn’t know the specifics. The thirty Americans took their oath of keeping the details of the experience secret during the war and even afterward. As the years went by and Albania remained under communism, the Americans still didn’t talk about it because they wanted to protect the Albanians who had helped them.”

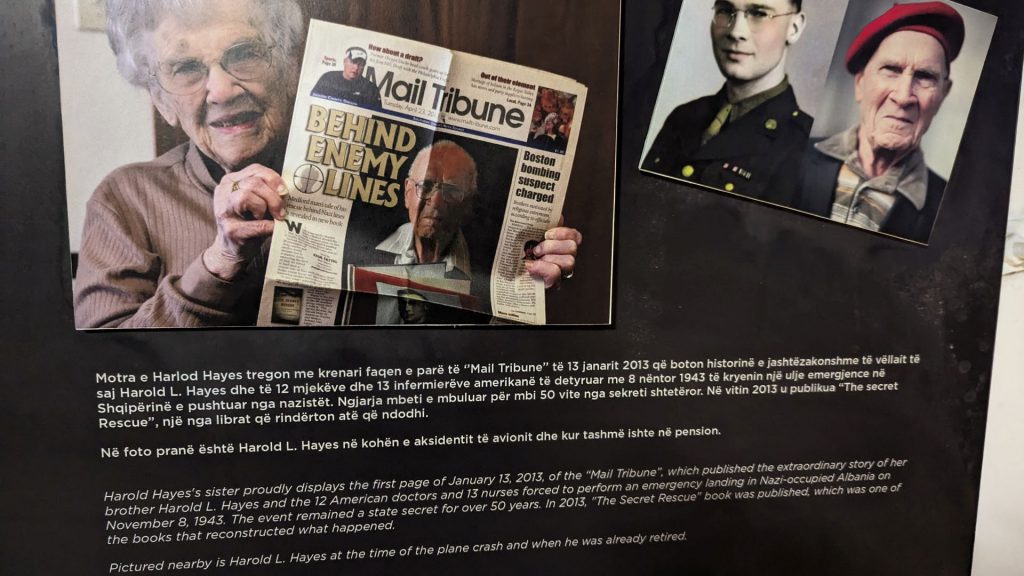

In fact, most members of the 807th kept mum until 2011 when Ms. Lineberry interviewed the only living survivor, eighty-nine-year old Harold Hayes, at a retirement home in Oregon, who was only 21 when the plane crashed.

Since then, the event has been revealed in six books published in the United States, whilst in Albania, it has been completely forgotten. The only ones who have written about it are the family members of Kostaq Stefa in the book of memoirs dedicated to their beloved man, now proclaimed “Martyr of Democracy.”

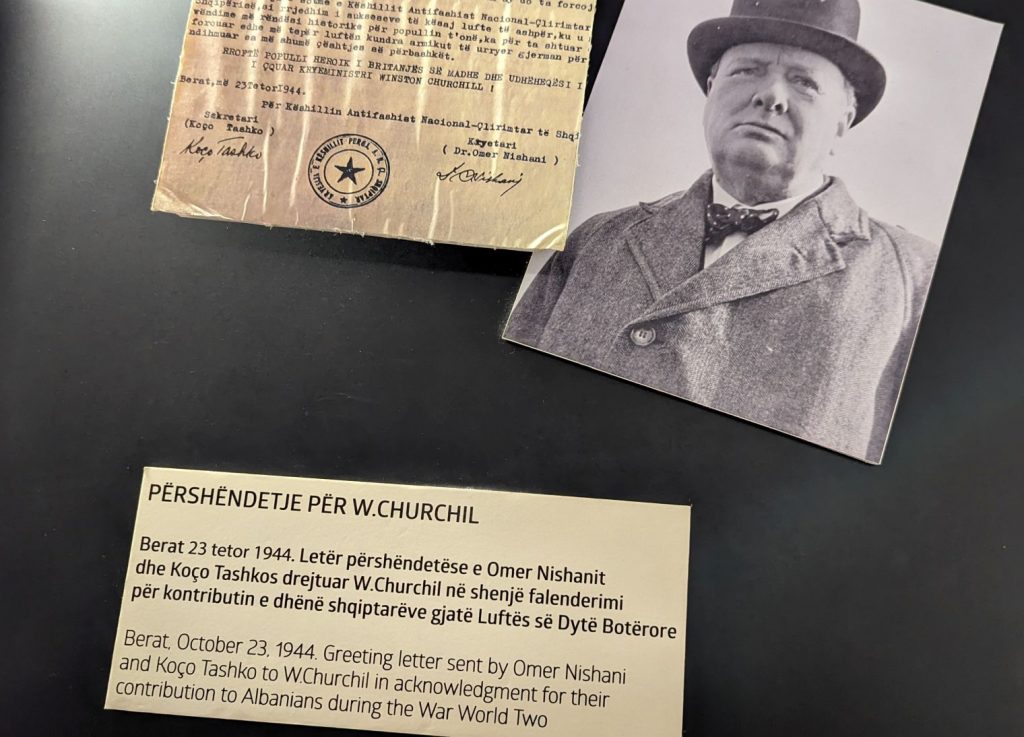

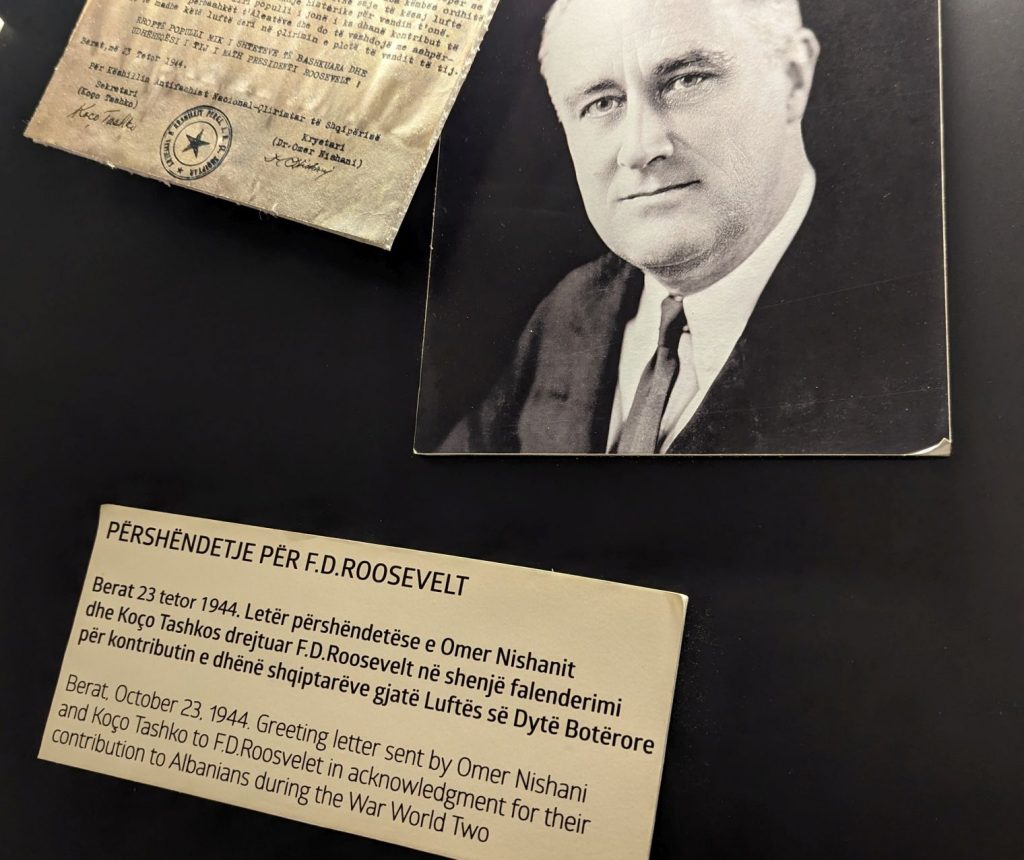

This is displayed in Bunk’Art 1. For those who can’t read the small print here (including me), this is what it says: “Harold Hayes’s sister proudly displays the first page of January 13, 2013, of the “Mail Tribune,” which published the extraordinary story of her brother Harold L Hayes and the 12 American doctors and 13 nurses forced to perform an emergency landing in Nazi-occupied Albania on November 8, 1943. The event remained a state secret for over 50 years. In 2013, “The Secret Rescue” book was published, which was one of the books that reconstructed what happened.

Pictured nearby is Harold L. Hayes at the time of the plane crash and when he was already retired.”

I don’t know why it says 12 doctors instead of 13. Maybe he meant himself and 12 others?

The Inter-Communication Room

The slogan of the communist regime, used even today by all world armies is: “Without inter-communication, there is no command and without command, there is no victory.” A part of the bunker that for secret reasons is separated even today from the rest of the tunnel was meant for the inter-communication plant. Some of the original devices used over the years by the Albanian army are exposed in this room. Those who look more modern were installed in the inter-communication unit of this bunker inaugurated by Enver Hoxha on June 28, 1968.

Immediately after the liberation from the Nazi and Fascist occupation (November 1944) Albania received another siege. The communist regime isolated the border areas with barbed wire with a system, which was called CLONI. The purpose of the electrical signaling barrier was to avoid any escape from inside, and any infiltration from the outside. Anyone who stepped into the electrical signaling barrier without authorization, could be executed on the spot accused of treason against the homeland.

The museum displays a sample of the fence. The strobe lights flash white or blue, which combined with the soundtrack, create a dark and eerie mood. It fits the subject matter.

This is the last piece of art you see before you exit Bunk’Art 1. Titled, “Promenade” this was made of ceramic and iron by Nicola Genco in 2019.

This is what the plaque reads, in its entirety:

“The strange and endless figures, which irregularly traverse the space, are figures of people coming from afar or going far away, leaving traces in seas and rivers, climbing to steep heights, walking in the lowlands and forests, crossing bridges, overcoming walls.

They are the shadows of those people who have turned a foreign country into their home, who have met the different and they have become different. White ceramic head and body, fragile and precious at the same time, to say that the mind and heart are the seat of consciousness and feelings; as well as the slender and long legs and rusty iron rods sunk into the ground to symbolize the length and ferocity of the journey, but also the perseverance and courage with which they faced it.

Nicole wanted to gather this variety of creatures on the land of no one, in a kind of basin between two shores to shed light on the invaluable value of the meeting of cultures, the undoubted importance of human relations, the important weight of ideas circulation, the undeniable usefulness of sharing experiences. The faces of travelers, synthetically modeled, prevent you from distinguishing gender, age, ethnicity. They are just people who go in front of each other, even to get to know themselves better.

It is clear, needless to say, that such a walk of theirs is not a promenade. (Lia De Venere)”

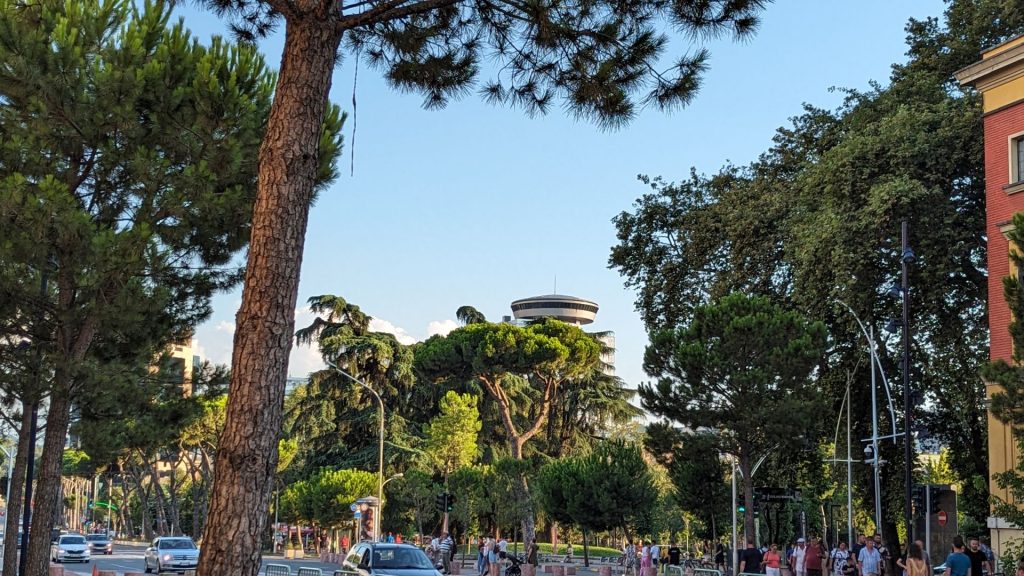

We will leave you today with just one more picture, of a UFO:

That is either a UFO (more likely) or the Sky Tower Restaurant, a revolving restaurant that revolves a full 360 degrees every hour. We wanted to eat there, but it was closed for renovations. Darn.

We will see you in the next blog when we share day eight with you.