It was time to drive south. We decided to break up the drive to Lisbon by stopping in Aveiro.

Aveiro, also known as the “Venice of Portugal,” is a popular tourist destination located along Portugal’s Silver Coast. It is famed for its canals, Nouveau architecture and colorfully painted Moliceiros boats. Of course we took a boat ride through the canals! We had a tour guide, but I had trouble hearing him, so I just enjoyed the views.

The first thing we saw when crossing the pedestrian bridge into town were the tour boats.

Then what we would call “main street.”

We made a reservation and were assigned to this pretty boat:

And we’re off!

That was a short, fun and relaxing stop! We arrived in Lisbon that evening.

We started our visit in Lisbon the next day by just walking around. We saw statues right away.

The statue on the left-hand side below is João Baptista da Silva Leitão de Almeida Garrett, viscount de Almeida Garrett (born Feb. 4, 1799, Porto, Port. —died Dec. 9, 1854, Lisbon). He was a writer, orator, and statesman who was one of Portugal’s finest prose writers, an important playwright, and chief of the country’s Romantic poets. For more, read a piece from Livraria Lello, the beautiful bookstore I visited and wrote about in a previous post: https://www.livrarialello.pt/en/almeida-garrett-

The statue on the right-hand side below is António Feliciano de Castilho (born Jan. 28, 1800, Lisbon—died June 18, 1875, Lisbon). He lost his sight at the age of six, but the devotion of his brother Augusto, and aided by a retentive memory, enabled him to go through his school and university course with success; and he acquired an almost complete mastery of the Latin language and literature. He became a classical scholar and at the age of 16 published a series of poems, translations, and pedagogical works. He was a poet and translator, a central figure in the Portuguese Romantic movement.

Then there was this substantial monument honoring the Marquis of Pombal. He is standing next to a lion. He is another “complex” figure, who did some good things for Portugal and some really bad things. The good things included (among others):

— instituting domestic administrative reforms and succeeding in elevating Portugal’s prestige in external politics

— granting civil rights to the “New Christians” (Jews – and others? – who had been more or less forcibly converted to Christianity)

— leading Portugal’s recovery from the 1755 Lisbon earthquake

On the down side, Pombal governed autocratically, curtailing individual liberties and suppressing political opposition, and fostered the black slaves trade to Brazil.

In 1777, Pombal was stripped of his offices and ultimately exiled to his estates, where he died in 1782. His legacy was only partially rehabilitated about a century after his death, due to efforts by his descendants, and remains highly controversial.

Articles, if you are interested in learning more about him:

https://www.algarvehistoryassociation.com/en/portuguese-history/portugal/126-the-marquis-of-pombal

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Marquis-de-Pombal

https://www.historytoday.com/archive/months-past/pombal-and-inquisition-portugal

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sebasti%C3%A3o_Jos%C3%A9_de_Carvalho_e_Melo,_1st_Marquis_of_Pombal

The next monument (pictures below) is the Monument to the Fallen of the Great War (a.k.a. the Monument to the Combatants of the Great War). It is dedicated to the soldiers of the Portuguese Army who died during the First World War. It features a personification of the Fatherland, in the form of a man in robes and bearing a flag, crowning a soldier of the Portuguese Army. On the sides are two large stone figures of men, bent under the main part of the monument, symbolizing their strive to keep the Fatherland standing. At the base of the pedestal is a bronze sculpture of military equipment, such as gas masks, helmets, ammunition belts, bags, etc.

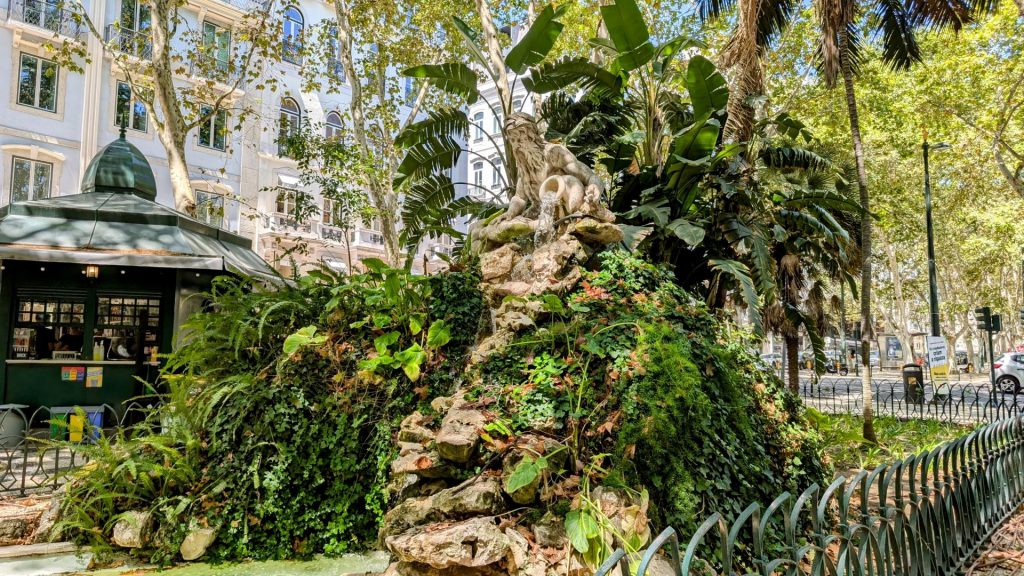

I don’t know if the guy (below) holding the tipped pot (from which water is actually flowing) is supposed to represent something, but it was a pretty.

The Monumento dos Restauradores (Monument to the Restorers) memorializes the victory of the Portuguese Restoration War. The Restoration War (Portuguese: Guerra da Restauração), historically known as the Acclamation War (Guerra da Aclamação), was the war between Portugal and Spain that began with the Portuguese revolution of 1640 and ended with the Treaty of Lisbon in 1668, bringing a formal end to the Iberian Union.

The monument is 30 meters high. Above the base stand two bronze allegorical figures: the one on the southern face, a winged male draped in a flag and holding the broken chains of foreign domain, is Independence; the one on the northern face, a winged classically-dressed female figure holding a palm on one hand and a laurel wreath on the other, is Victory. The remaining two signs show stone panoplies.

As you may know by now, I like pretty and interesting buildings. In my opinion, these fit the bill:

This is the Lisboa Rossio, the train station:

The fountain pictured below is the south fountain at Rossio Square. (The official name of the square is Praça Dom Pedro IV, but the locals prefer to use its old name, “Rossio.”)

This fountain contains an elaborate sculptural set, composed of a central body topped by four fish that squirt water into a small basin under which four children can be observed. The children, back to back, are connected to each other through their hands. Each has the right palm facing down in a gesture of receiving and the left palm facing up in a gesture of giving.

From there, water overflows into an octagonal-shaped and large basin, which in turn pours water into a circular stone lake.

Under the second basin there are four seated figures grouped in pairs: Acis and Galatea, and Poseidon and Aphrodite.

Inside the lake are four mermaids carrying conch shells that project water in the direction of the second basin.

The bronze sculptures were created by sculptors Mathurin Moreau and Michel Lienard, and were installed with the fountains in 1889.

There are actually two identical fountains in the square. In between the two fountains, in the center of the plaza, on a 23 meter-high pedestal, stands an imposing bronze statue: Monumento a Dom Pedro IV. It is dedicated to King Peter IV whose reign in Portugal was brief but significant. He is depicted holding the Portuguese Constitution that he fought to protect, and at his feet are four female figures representing Justice, Wisdom, Strength and Moderation – virtues attributed to Peter IV.

Here is a picture that includes one of the fountains, the monument to King Peter IV and one other piece of art about which I have no information.

We were now headed to the Castelo de São Jorge. On the way, we passed this lift which supposedly provides a great view of Lisbon. However, after standing in line for 15 minutes without moving or seeing any activity at all, we skipped it. But it is kinda cool looking.

Castelo de São Jorge (Castle of Saint George)

Human occupation of the castle hill dates to at least the 8th century B.C., while the oldest fortifications on the site date from the 2nd century B.C. The hill on which Saint George’s Castle stands has played an important part in the history of Lisbon, having served as the location of fortifications occupied successively by Phoenicians, Carthaginians, Romans, and Moors, before its conquest by the Portuguese in the 1147 Siege of Lisbon. Since the 12th century, the castle has variously served as a royal palace, a military barracks, home of the Torre do Tombo National Archive, and now as a national monument and museum. The grounds are lovely and the views spectacular.

The statue below is of Olisipona. In the Ancient World, Lisbon was known as Olisipo. Lisbon’s name was written “Ulyssippo” in Latin by the geographer Pomponius Mela, as “Olisippo” by Pliny the Elder, and by the Greeks as “Olissipo.”

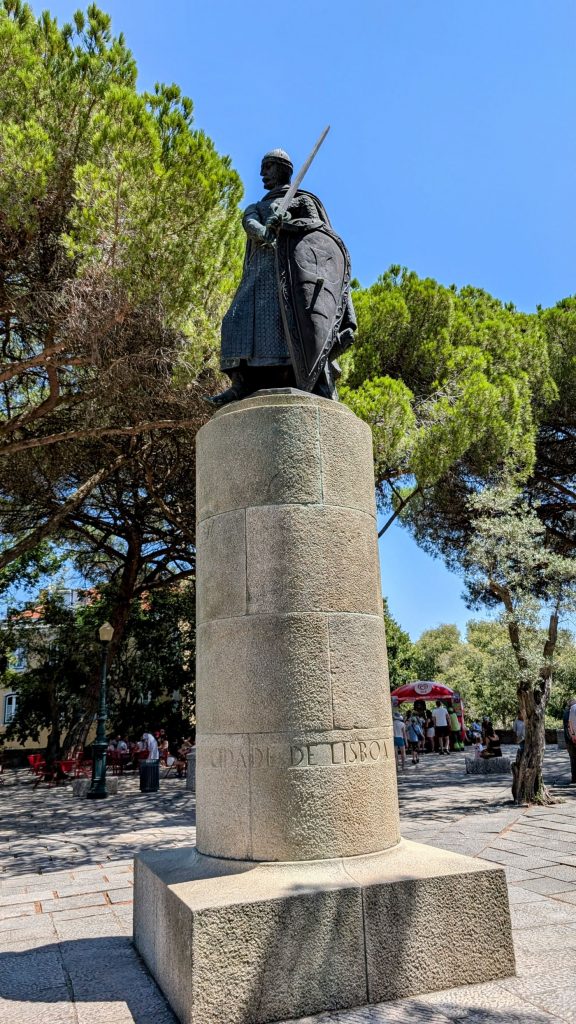

The sculpture of Afonso Henriques, first king of Portugal, is situated in the middle of the Place-of-Arms and is a bronze replica of the original, by Soares dos Reis (1847-1889), which can be found in Guimarães. This sculpture was a gift from the city of Porto to the city of Lisbon, during the commemorations marking the 700th anniversary of the conquest of the city on October 25, 1947.

There is a huge flat area on the grounds. I don’t know what it was used for, but gatherings and group yoga come to mind.

Pictured below is King Manuel I of Portugal. Also known as “the Fortunate,” he was the fifth king of the second dynasty and reigned from 1495 until his death. He is best known for overseeing the formation of the Portuguese empire with several Portuguese “discoveries” made during his reign. He sponsored Vasco da Gama which led to the discovery of the sea route to India in 1498 and began the Portuguese colonization of the Americas, as well as the establishment of a trade empire across Africa and Asia.

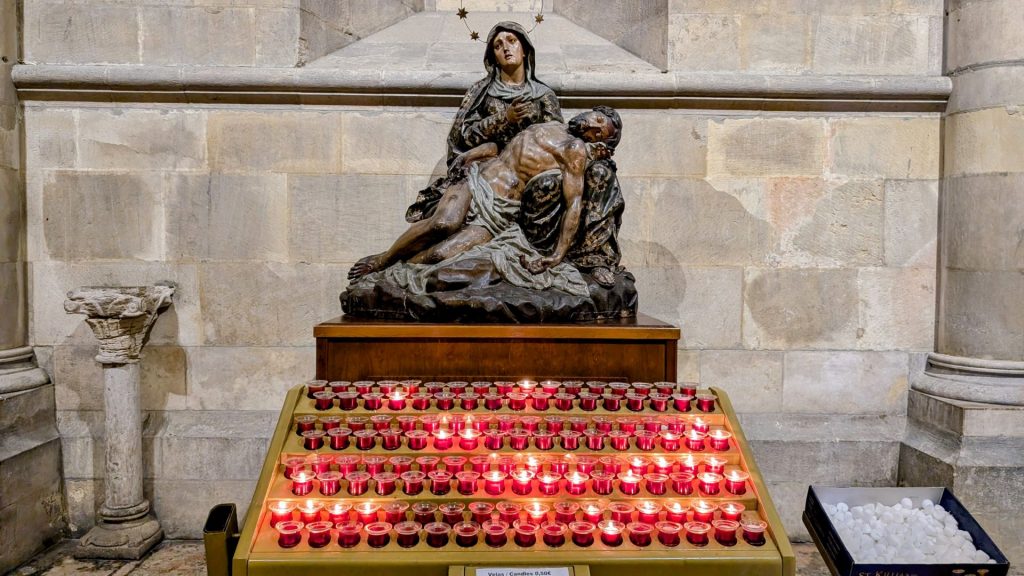

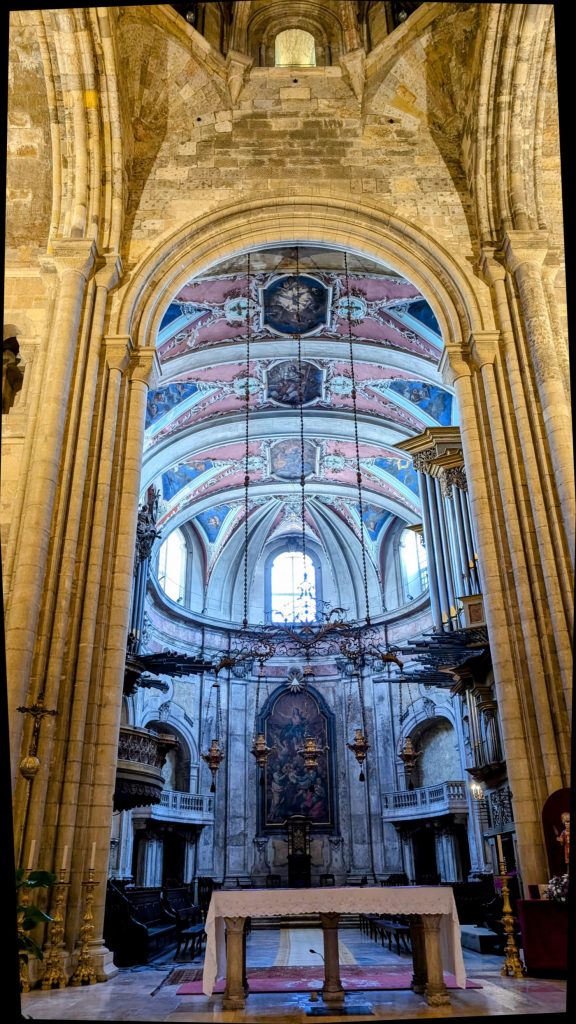

Our next stop was the Lisbon Cathedral, better known as Sé de Lisboa. It is the oldest and most important church in the city. Its construction dates back to the 12th century and is predominantly Romanesque in style. From the outside, the cathedral is protected by thick walls framed by two bell towers, which give it an appearance more typical of a medieval fortress than of a church. The façade’s centerpiece is a central rose window.

Amid its austere character, the interior has some decorative elements and a striking 14th-century Gothic chapel.

Our last visits before heading to the marina for our evening boat ride, included Praça do Comércio (Commerce Square), the Rua Augusta Arch, and Cais das Colunas.

Lisbon’s most important square, the Praça do Comércio, was built on the site where the old Royal Palace used to exist before it was destroyed by the earthquake of 1755. It was for decades Lisbon’s main entrepôt, and crucial for its maritime trade.

The southern end of the plaza is open and looks out onto the Tagus River. The other three sides have yellow-colored buildings with arches all along the façade. When the square was first built, the commercial ships would unload their goods directly onto this square, as it was considered the “door” to Lisbon.

The bronze equestrian statue of Joseph I of Portugal (1750 – 1777) was designed by Machado de Castro in 1775. Joseph I was King of Portugal during the Great Earthquake.

Located on the northside of Commerce Square is the Rua Augusta Arch which gives way to the boulevard Rua Augusta, the most prominent boulevard in Baixa.

This triumphal arch was designed by the Portuguese architect Santos de Carvalho to celebrate the reconstruction of Lisbon after the 1755 earthquake. It was completed in 1873. On top of its several pillars, it’s adorned with numerous statues that represent important Portuguese figures like Vasco da Gama and the Marquis of Pombal.

Cais das Colunas is located at Praça do Comércio. Its marble steps used to be the noble entrance into the city, through which heads of state and other prominent figures have arrived. It used to give access to ferry boats and other vessels connecting Praça do Comércio to the Tagus’ south bank.

The pier was named after the two columns (colunas) that can be seen on the side of the main steps. These simple yet elegant pillars were designed by architect Eugénio dos Santos and were part of the city reconstruction plan after the 1755 earthquake nearly destroyed it. The two columns are replicas of those thought to have been in Solomon’s temple. They’re representative of wisdom and devotion.

Sights we happened to see on the way to the marina:

The Jerónimos Monastery is a National Monument and was classified a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1983. King Manuel I built a large monastery near the location where the Infante D. Henrique ordered a church to be built in the mid-15th century by invocation of St. Mary of Belém. To immortalize the memory of the Infante, for his intense devotion to Our Lady and faith in St. Jerome, in 1496 King Manuel I decided to found the Monastery of St. Mary of Belém, near the city of Lisbon, next to the Tagus River. Donated to the monks of the Order of St. Jerome, today it is commonly known as the Jerónimos Monastery.

At 52 meters (170 feet) tall, Lisbon’s Monument to the Discoveries (below) commemorates the 500th anniversary of the death of Henry the Navigator, who discovered the Azores, Madeira, and Cape Verde.

The Monument to the Discoveries is made up of a group of sculptures that represent the prow of a caravel (a small sailing ship constructed by the Portuguese to explore the Atlantic Ocean). Leading the ship is Prince Henry the Navigator, followed by many other great Portuguese explorers who played key roles in the major discoveries of Portugal’s history.

Cruise time! We will get to see some of these and more from the water now.

One of the first things we passed was the Belém Tower (Torre de Belém). The tower was built between 1514 and 1520 in a Manuelino style by the Portuguese architect and sculptor Francisco de Arruda. This tower symbolizes Portugal’s maritime and colonial power in early modern Europe. It was built during the height of the Portuguese Renaissance. It is a prominent example of the Portuguese Manueline style, but it also incorporates other architectural styles, such as the minarets, which are inspired by Moorish architecture. This tower was used to defend the city. Years later, it was transformed into a lighthouse and customs house. The structure was built from lioz limestone and is composed of a bastion and a 30-meters (100 ft), four-story tower.

It was classified as a World Heritage Site in 1983 by UNESCO.

I’ve been noting that this isn’t the Golden Gate Bridge (pictured below), and, of course it isn’t. It is the 25 de Abril Bridge. That said, both bridges were designed by the American Bridge Company. This is why the 25 de Abril Bridge looks a bit like the Golden Gate and why they are often compared.

At 1.4 miles (2,277 meters) long, the 25 de Abril Bridge holds the record for the longest suspension bridge in Europe and was the first bridge to be built in Lisbon. It has two levels, the top level is for cars, and the lower, which was added in 1999 is for trains.

At the time of its inauguration in 1966, the bridge was named Salazar Bridge (Ponte Salazar), after Portuguese Prime Minister António de Oliveira Salazar, who ordered its construction. After the bloodless Carnation Revolution in 1974, which overthrew the remnants of Salazar’s Estado Novo regime, the bridge was renamed for April 25, the date of the revolution.

Off in the distance, you can see a tower with a cross on top. It is Cristo Rei. It dates from the 1950s, and its construction represents Portugal’s religious gratitude for avoiding the horrors of World War Two. Since its consecration in 1959, Cristo Rei has been an important Portuguese pilgrim destination, and today is a major religious center for the diocese of Setubal.

The sun was getting low in the sky as the sail and our fabulous day in and near Lisbon drew to a close.