Our next stop was Lagos. We first walked by the fortress. It was built in the 17th century, as one of the main components of a system of maritime fortifications to defend the city, then headquarters of the military government of the Algarve. Significant restoration work has been carried out over the years and the fort is considered to be one of the best-preserved 17th century fortifications in the Algarve region.

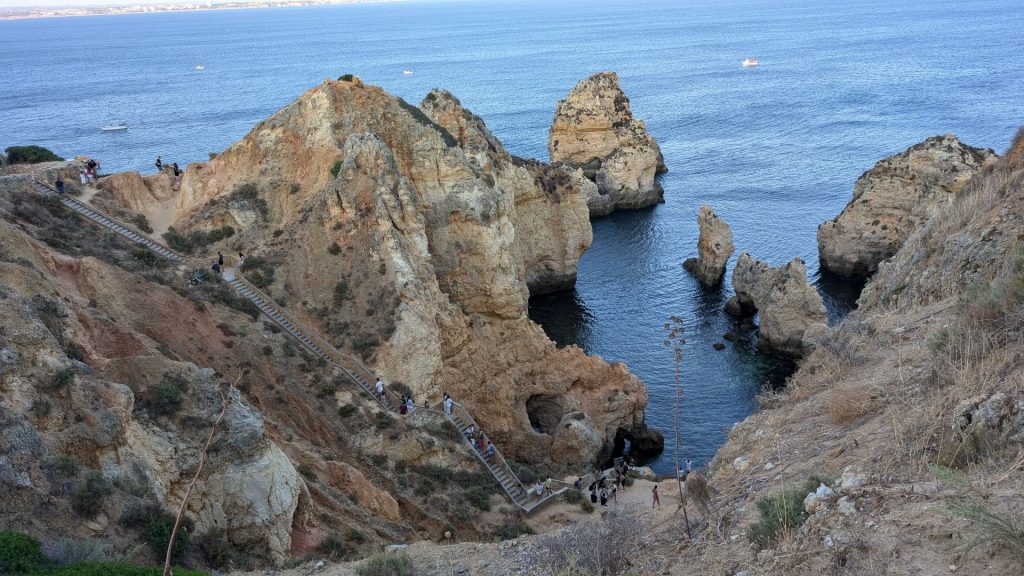

To the coast! The coastal path is nice because it takes various forms (dirt, boardwalk) and provides numerous opportunities to get a birds eye view or go down to the water. And the rock formations all along the way . . . stupendous!

At one point, you have to use city streets for a short time. I stopped to shop (not).

Back to the coast:

We walked around town a bit the next day. The square has a a couple of interesting statues and this cool bike that includes a flower pot.

Statue of King Sebastian I or Estátua de El-Rei D. Sebastião

Standing in Praça Gil Eanes (Gil Eanes Square), this statue (pictured below) by João Cutileiro has been described by the art historian José Augusto França as one of the most beautiful examples of sculpture to be found to the south of the River Tagus.

Inaugurated in 1972, it perpetuates the memory of Sebastian I, the king who raised Lagos to the category of a city in 1573 and later set sail from here in 1578 in a failed attempt to conquer Alcácer Quibir, in what turned out to be a fatal military expedition to Morocco. Two years after this defeat, King Philip II of Spain took over the Portuguese Crown and brought about the dynastic union that was to last until 1640.

The disappearance of King Sebastian led to the formation of the “Myth of Sebastianism,” which has endured in the memory of the people, being perpetuated in Portuguese literature and philosophy until the 20th century. The people refused to accept the king’s tragic and fatal destiny and believed that one day he could come back to them, walking towards them out of the fog.

The statue that is lying down is appropriately called Venus Recumbent. Designed by João Cutileiro, this marble piece was created in the eighties.

We left the square and walked a short distance to see the caravel Boa Esperança, a replica of the ship Bartolomé Díaz used when he passed the Cape of Good Hope in 1488. The vessel was constructed in Portugal by skilled shipbuilders using traditional techniques from that era. Launched in 1990, it immediately began ocean sailing and was acquired by the Algarve Tourism Board to showcase the region’s history. Since then, the ship has traveled many nautical miles on important missions and participated in regattas. It has also been featured in documentaries and films, offering guided tours to tourists and students about the Age of Discovery and the lives of seafarers from the 15th–17th centuries.

Michael suggested we stop to view the Cavaleiro Medieval sculpture in Castro Marim, Portugal, on our way to Seville, Spain. So we did!

Seville

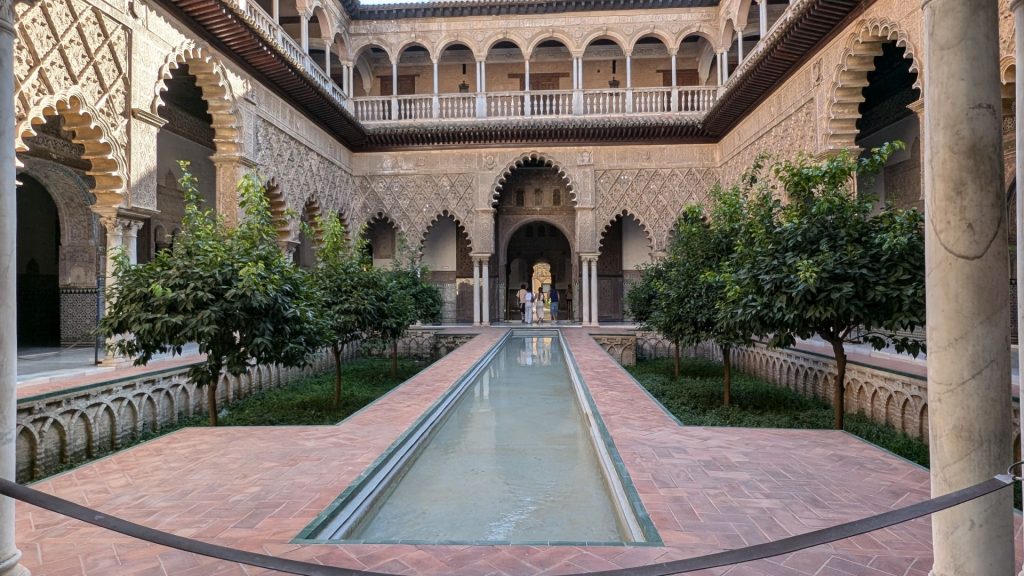

We spent a fair amount of the first afternoon at The Royal Alcázar of Seville.

Here’s some info from combined sources:

The Royal Alcázar of Seville is a group of palaces surrounded by a wall. Designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site, the Alcázar is the oldest royal palace in Europe that is still in use today.

History time!

Since the city was founded, Seville’s evolution has been closely linked to the River Guadalquivir. Its political and demographic supremacy in many periods of history was largely due to its being on the last navigable point of the river for ships of a certain draft.

Thus, the Iberians’ Seville, called Ispal, which was home to the flourishing civilization of Tartessos around 700 B.C., became the Hispalis of the Romans in 200 B.C. and it was later named Isbiliya by the Muslims following the Arab invasion of the Iberian Peninsula in 711 A.D.

In the 11th century, the city’s fate was forever tied to the Alcazar of Seville, a fortress designed to protect the plaza on the banks of the Guadalquivir and to accommodate the Muslim king’s residence and the offices of the state administration.

From then on, Seville and its Royal Alcazar evolved in unison, sensitive to the intervention of each one of the monarchs who ruled within its walls and who in the majority of cases greatly admired what their predecessors had constructed. That is why its architecture is so varied, combining Islamic, Gothic, Renaissance, Baroque, and Romantic elements, as well as some of the finest examples of Mudéjar art, which is the product of both Islamic and Christian cultures. It is because of the admiration for all that has come before that the Royal Alcazar of Seville has been so well preserved. Numerous books on architecture have studied its rich, ornate structure.

Sadly, we didn’t get to visit the Upper Rooms. Tickets to those were limited to times that did not overlap with our entrance tickets. I guess we didn’t read enough in advance. And I guess we have to go back!

We entered here:

This lead us directly into the main courtyard. The Monteria (Hunting) Courtyard is the organizer of the palace buildings: The Mudéjar Palace, the Gothic Palace and the Admiral’s Hall.

The current configuration as architectural space and anteroom of the Palaces, comes from the period of the Palace of King Peter I construction, in 1364. Under the slabs of this courtyard were found the ruins of different 12th century Almohad palaces. (The Almohad Empire was a North African Berber Muslim empire founded in the 12th century.)

This space soon became the meeting point for the nobility that participated in hunts organized by the Spanish kings (hence its name). In the early 16th century, with the founding of the House of Trade for the Americas (La Casa de Contratación de Indias) by the Catholic Kings, the courtyard soon became the Alcazar of Seville’s real center of gravity. The House of Trade, which in the year 1504 took up the southern side of the Hunting Courtyard, was created in order to control trade with the Americas, whose colonization had started just eleven years prior.

Thus, these installations within the Royal Alcazar were transformed, over a period of two centuries, into the logistics center of the first global empire in the history of humankind, an immense task that included the control and the monopoly of American goods coming into the Sevillian port, the drafting of new laws that regulated such trade, the training of navigators who would be able to guide the sailing vessels through the oceans as well as the formation of cartographers.

The Monteria (Hunting) Courtyard

The House of Trade:

The painting in the center of the first picture is Virgin of the Navigators. It was painted by Spanish painter Alejo Fernandez sometime between 1531 and 5136.

Admiral’s Hall

This beautiful hall was part of the first headquarters of the House of Trade, established in 1503 by Queen Isabella I of Castile to regulate trade in the Americas after the discovery of the new world. Although this hall was part of the House of Trade, it got its name for a different reason. It was the headquarters of the Tribunal del Almirantazgo de Castilla (Admiralty of Court of Castile). Many famous (and infamous) explorers from Spain and neighboring countries visited this hall for a variety of reasons.

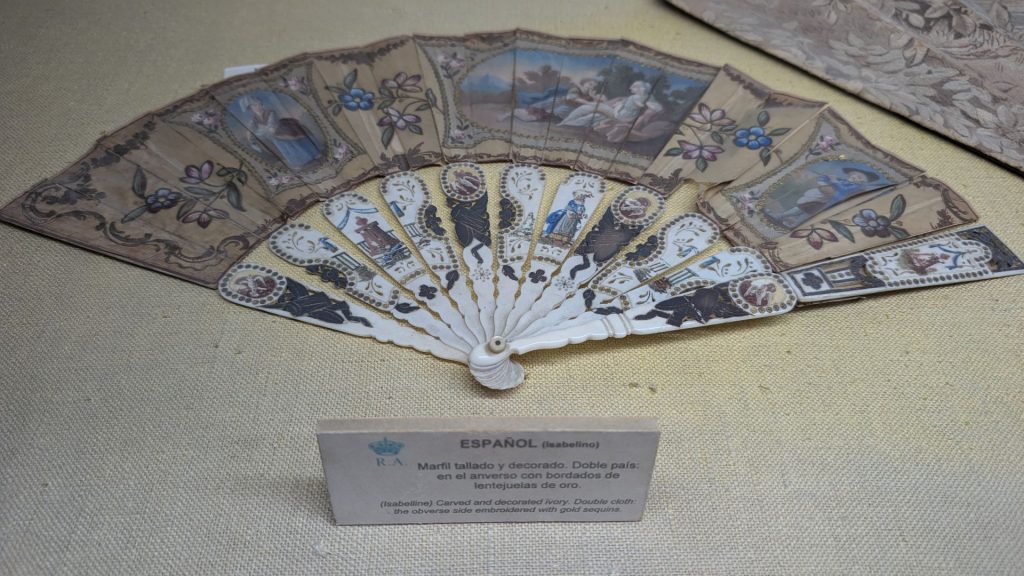

I bet you can’t guess where else went. The Fan Room. Yep. The fans were quite varied, beautiful, and often exotic. I took a picture of four of them. Here are the descriptions printed on those little cards:

Top left: Ostrich feathers with amber ribs and frame

Top right: Richly carved seashell ribs with cloth showing a typical scene

Bottom left: Carved and decorated ivory. Double cloth: the obverse side embroidered with gold sequins

Bottom right: Ostrich feather fan. Tortoiseshell ribs and frame

The staircase leading to the Upper Palace is the most important of the whole palace. It was built during the reign of Philip II in the 16th century. The ceramic plinth that decorates its walls is a copy of the originals which are at “Madre de Dios” Convent in Seville. The front wall tapestry was created in Brussels during the 17th century and represents a mythological scene, “Dido and Aeneas,” in which Virgil was inspired to compose his famous Aeneid.

Let’s talk ceramics. Seville and Triana, the city’s pottery district, were once an important center of ceramic production. Maritime traffic was the best means for the commercial distribution of ceramics; this material could also serve as a container for other produce (oil, wine, mercury, etc.) and its weight made it ideal ballast for ships. Consequently, the ceramics reached all the overseas destinations of ships sailing from Seville, or for which Seville was a port of call.

Here are a few examples of their ceramic tile handiwork and when and how the tiles were used.

Arista tiles served to fill early Renaissance 16th-century Andalusian architecture with color during the reigns of the Catholic Monarchs and Emperor Charles V. Some motifs were formed with a single tile and others with four tiles. Walls were protected and decorated with them to form panels resembling vertical or horizontal carpets. The conventional structure was transformed by tiles of different motifs, sizes and shapes, depending on their placement.

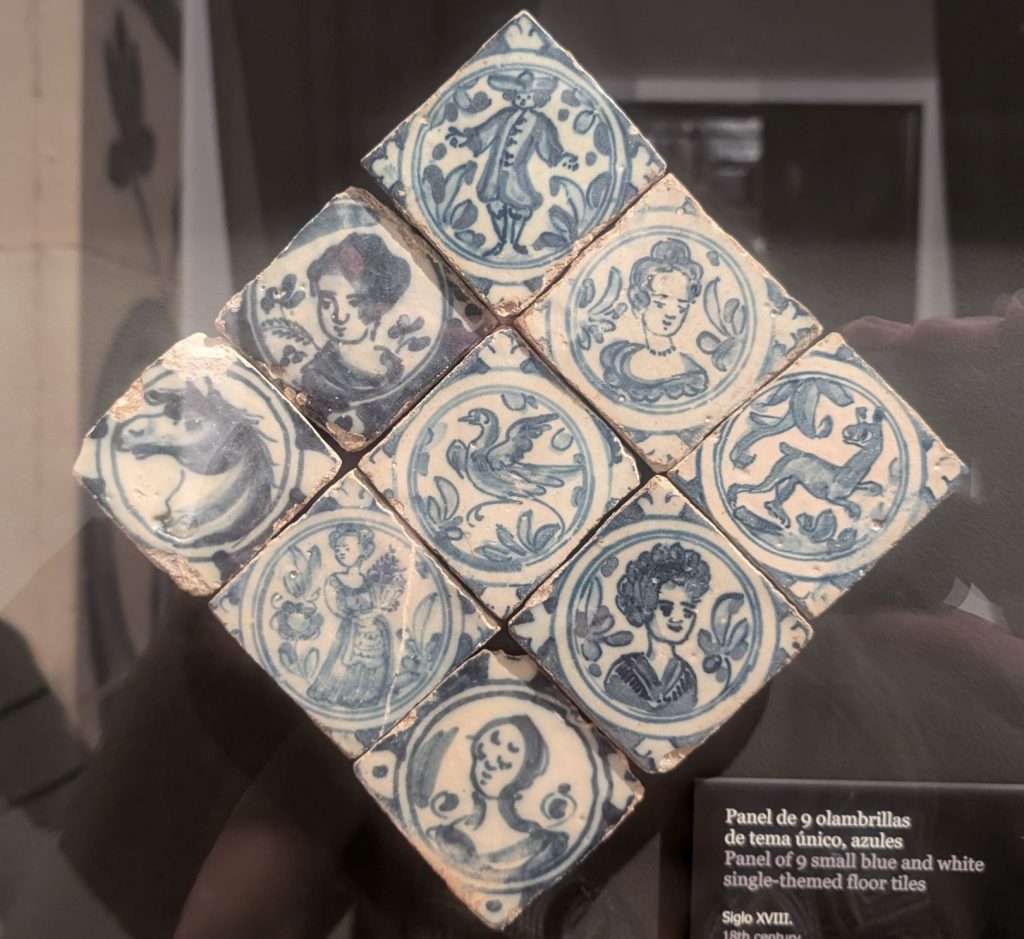

Although there were exceptional cases in the Seville of the 14th and 15th centuries where floors were completely covered in glazed tiles, it was more common in the 16th century for rectangular unglazed terracotta blocks to be combined with small decorative insert tiles call olambrillas, which filled the spaces left between the former to create expanses with different geometric designs.

The building technique for ceilings using wooden beams combined with boards or, often, large terracotta blocks was common in the architecture of the Visigoths in the 7th century. During the 16th century many rectangular arista tiles with support bands were manufactured in Seville for use on wooden ceilings. When these were custom made, they often included emblems or symbols alluding to the ownership of the building.

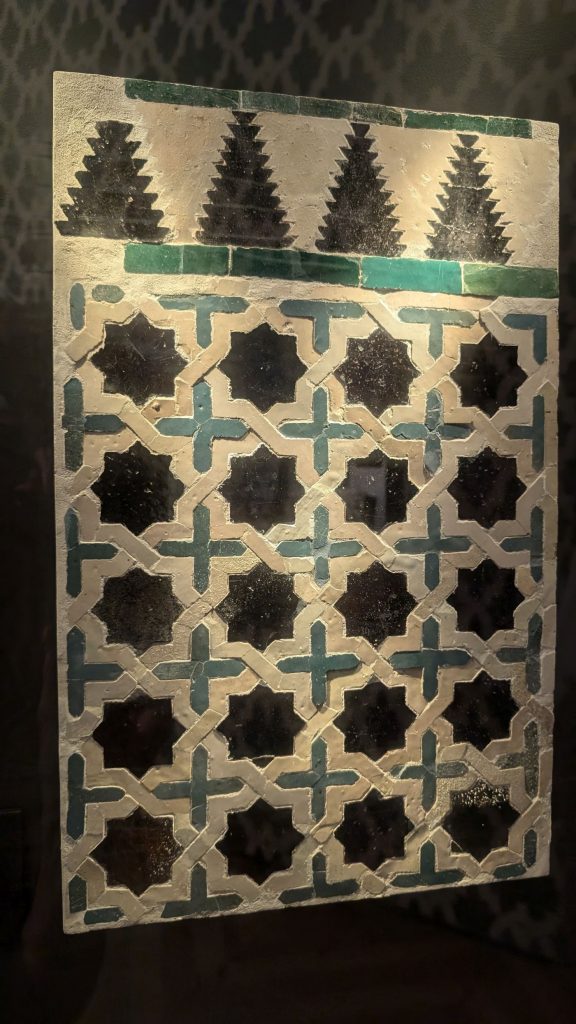

The fascination with perfect geometry is captured in this example of tile mosaic. The colors, meticulous execution, the small tiles and the type of crenellations crowning the compositions lead this tiled fragment to be attributed to the artisans who in the 14th century decorated the Alhambra in Granada in the time of Muhammad V and the Royal Alcazar of Seville during the reign of Peter I of Castile.

Decorated with a single motif within a circle, this type of tile originated in Italy in the 16th century, but it was particularly developed in the 17th century in the Netherlands. Accordingly, these tiles are also known as <<Delft-style>> tiles, in honor of the famous Dutch town where this type of pottery was produced. The range of motifs produced in Seville is varied and anecdotal, and the possibilities for their application in architecture were great. (You can probably read the description in the picture, but I also included it in the caption.)

Entrance Hall, Palace of Pedro I

Going through the main door of Palace of Pedro I is the Entrance Hall, where there are two narrow passages with right-angle bends to keep the privacy of the interior spaces, following the Islamic custom. On the left side is the entrance to the protocol area: “Patio de las Doncellas” or “Maidens’ Courtyard, and on the right is the access to the home area: “Patio de la Muñecas” or “Courtyard of the dolls.”

The Palace of King Peter I

In the second half of the 14th century, Peter I (also known as Peter the Cruel), the King of Castile, not only admired Islamic culture and surrounded himself with Muslim advisors and Jews, but even signed a pact of mutual assistance with the Nasrid Sultan of Granada (in theory his enemy ) so that he could defend himself better against domestic foes. Thanks to this liberal attitude and cultural and religious tolerance the Alcazar of Seville’s walls now boast the spectacular Palace of King Peter I.

The Castilian monarch greatly appreciated the Muslim’s architectural heritage and summoned artists and artisans of Arab and Berber origin from Toledo, Granada and Seville itself to build a new palace between 1364 and 1366 according to the canons of Moorish art, a more genuinely Spanish style, a combination of cultures that coexisted on the Peninsula for eight centuries despite facing each other on the battlefield. It was this interplay that resulted in epigraphs on the palace walls such as “Glory to our Lord the Sultan Peter!” and “May Allah protect Him!,” a clear example of this cultural fusion.

The Hall of the Ambassadors (Salon de los Embajadores) dates from the 14th century, when Pedro I of Castile made it a centerpiece of his new royal palace. It was the main hall of the palace, used as the throne room of Pedro I, where he received important personalities of his time. The room is square, similar to the Muslim “qubba” in which the square symbolizes the earth and the dome would be the Universe. A muqarnas decoration forming a star unites the square with the circle. The wrought iron balconies were made during the time of Philip II, at the end of the 16th century. The frieze that runs along the upper part of the room contains portraits of the Spanish monarchs, painted by Diego de Esquivel in 1599.

After its construction, the palace converted into the regular residence for the Kings of Castile and later on was used by the Kings of Spain, and undoubtedly became the most magnificent example of the one thousand-year-old architecture of Seville’s Alcazar.

The Gothic Palace

Ferdinand III, the King of Castile who conquered Seville in 1248, was unable to enjoy the Alcazar for very long as he was to die there just four years later. Alfonso X succeeded his father, Ferdinand III, as King of Castile

In contrast to Muslim taste for more reduced spaces of moderate height, with maze-like layouts designed for greater privacy, Christian monarchs’ tastes differed somewhat as they preferred loftier and more spacious rooms, and opted for a clear hierarchy in the different areas of the palace. Therefore, for this reason and for the prestige that Gothic art, imported from France a few decades earlier, had acquired in the Peninsula, Alfonso X chose this style to build his own palace inside the Alcazar of Seville .

Gothic forms, moreover, were strongly associated with Christianity and the Crusades, and the King’s choice for this genre symbolized the Christian Western world’s victory over Islam. Thus, the King of Castile invited masons who had worked on the naves of Burgos Cathedral, a Gothic milestone in peninsular architecture, to construct his new royal residence alongside the vestiges of the old Almohad palace.

The Tapestries Hall is located in the Gothic Palace. The hall was completely destroyed after the earthquake of Lisbon in 1755 and was remodeled by Sebastian Van Der Borcht. The tapestries that decorate the room are an exact replica of the original “The conquest of Tunisia” commissioned by Carlos V after his victory in 1535.

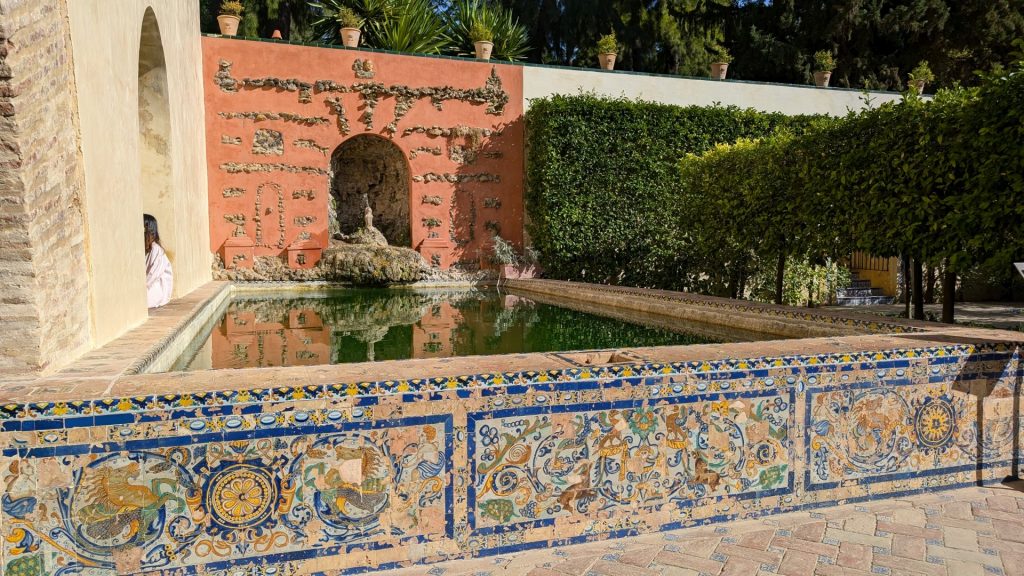

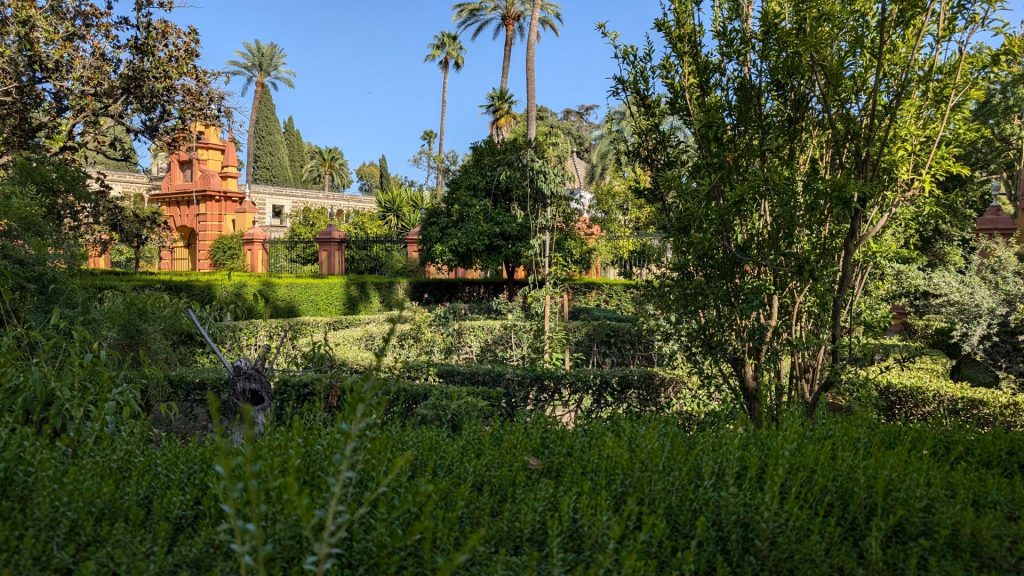

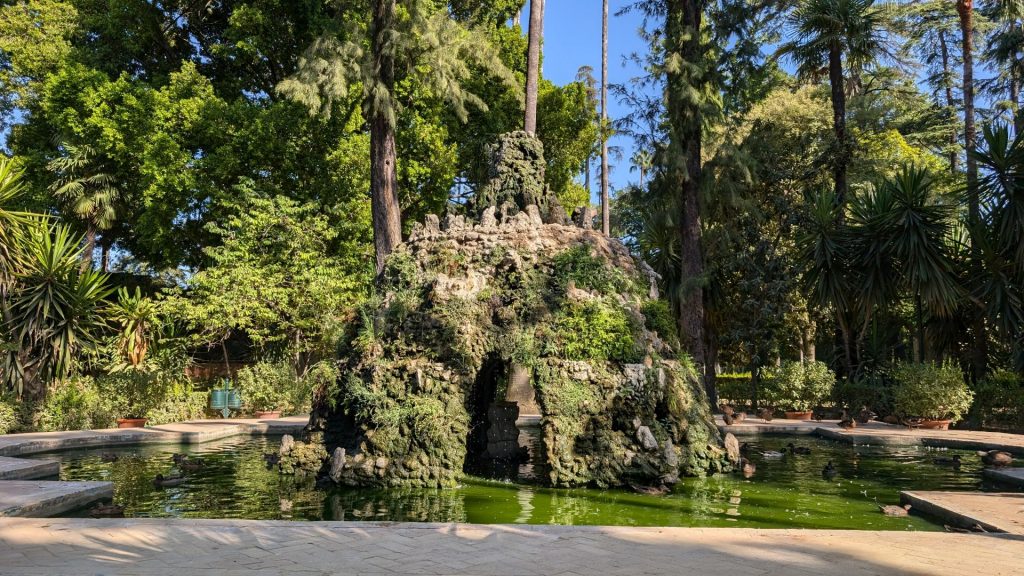

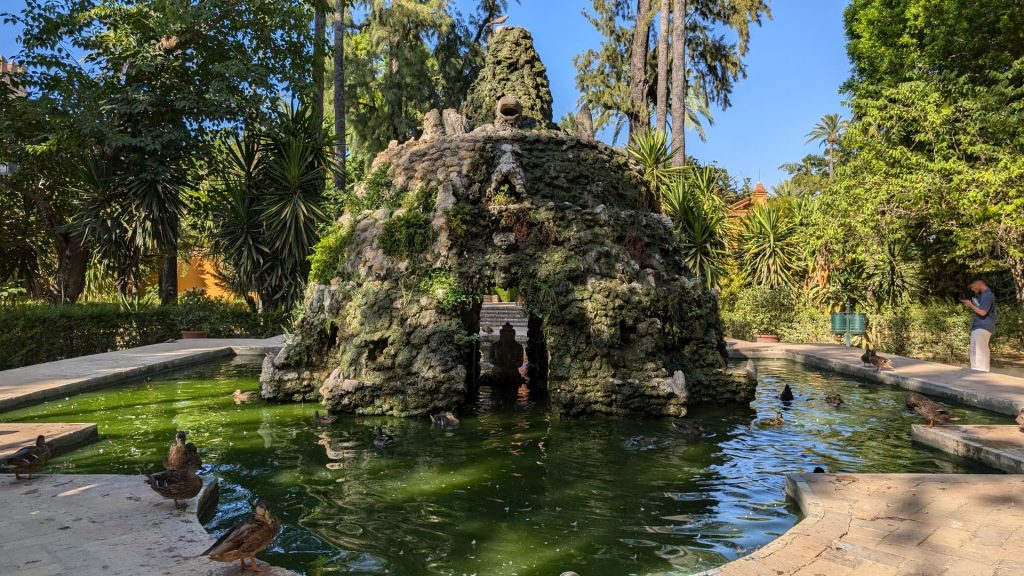

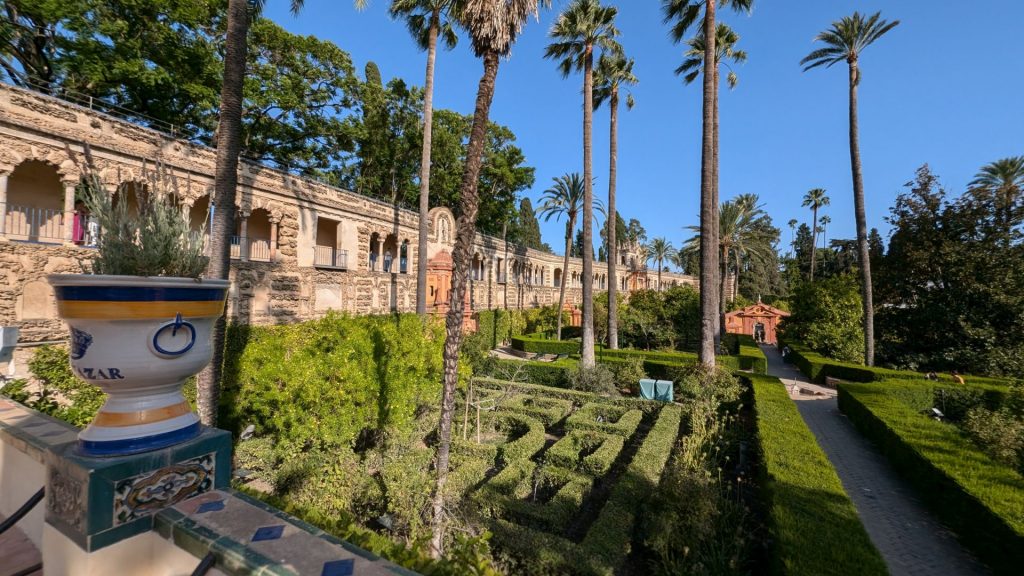

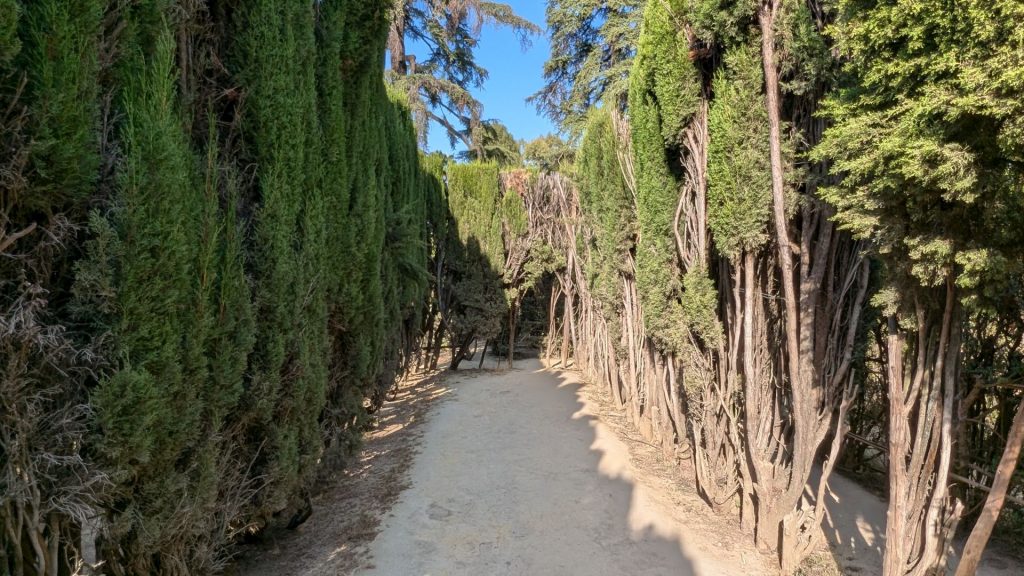

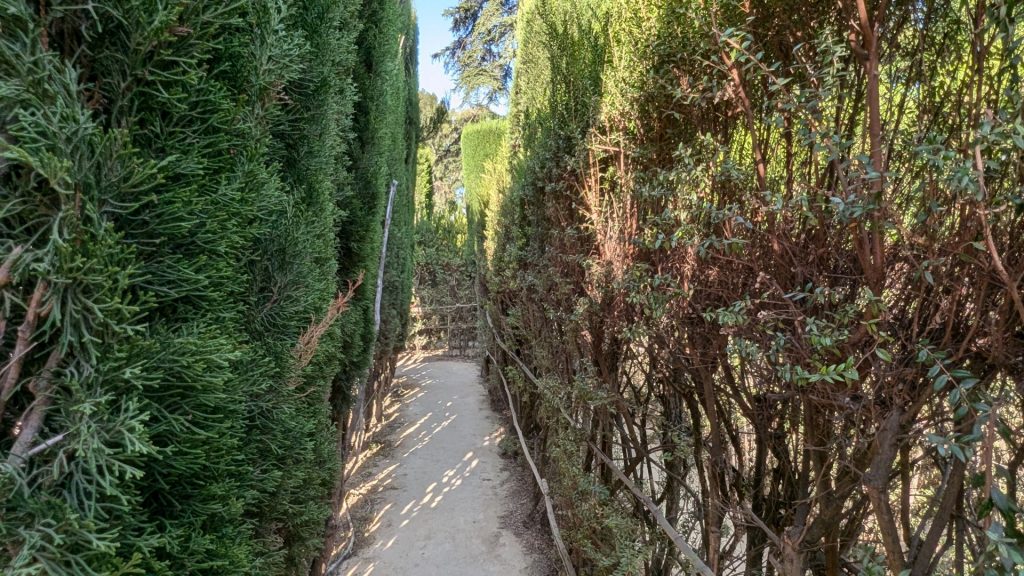

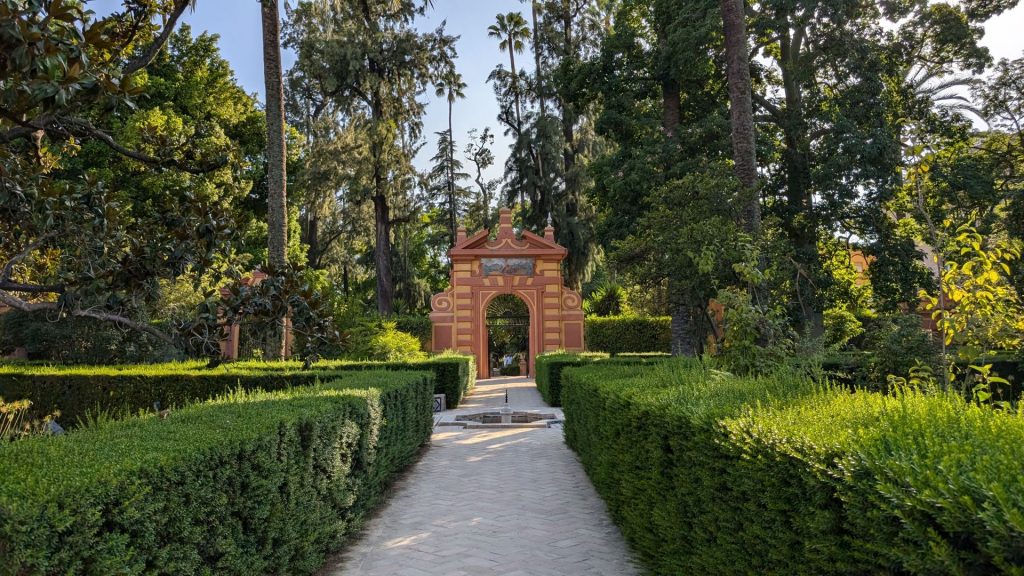

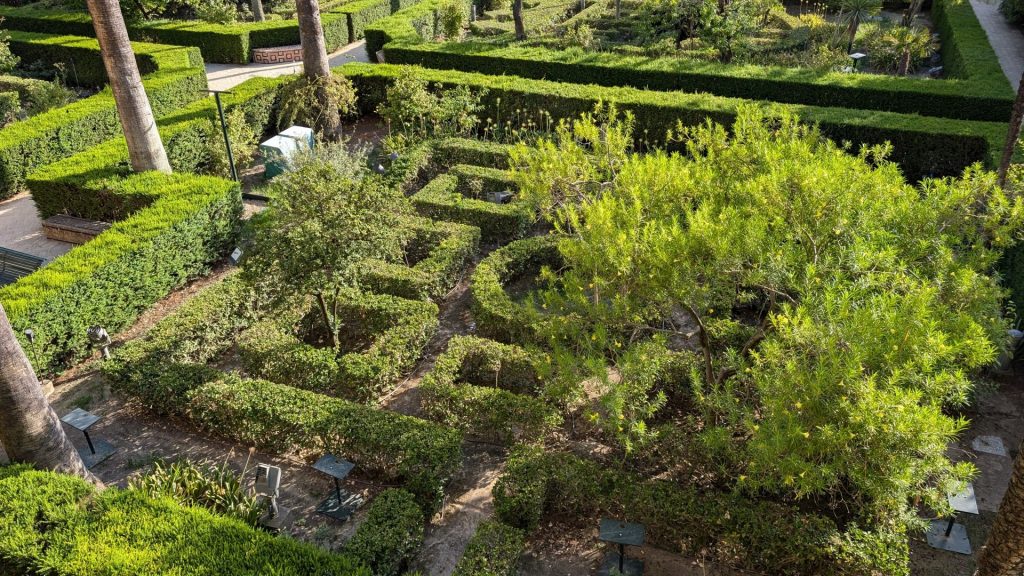

Oh my gosh, I haven’t even shown you the grounds and gardens yet! During the period of Muslim rule, the Royal Alcazar boasted an extensive area used for gardens, cultivation and corrals. In addition to providing fresh food to the members of the royal court, these spaces also had an aesthetic function. Every care and detail was taken to stimulate the senses: fragrant herbs and flowers were planted, trees were ordered into geometric patterns, pond water was used for its reflection and cooling properties and fountains and water jets were installed for their soothing sound.

Comparable to an oasis, the orchards also tied in with the ideas of the Koran, which often identifies a garden paradise, and thus this area was also considered a suitable environment for meditation. After the Christian Conquest and especially from the reign of Emperor Charles V onwards, the ancient Muslim gardens gradually came to lose their original layout to adapt to the changing tastes of the royal court.

Successive renovations carried out in the Royal Alcazar of Seville between the 17th and 20th centuries resulted in an arrangement that was absolutely unique in Europe, in which nature and architecture were cleverly combined to create a wide variety of environments which used trends and influences as different as Mannerism, Romantic Naturalism, Historicism and English landscaping.

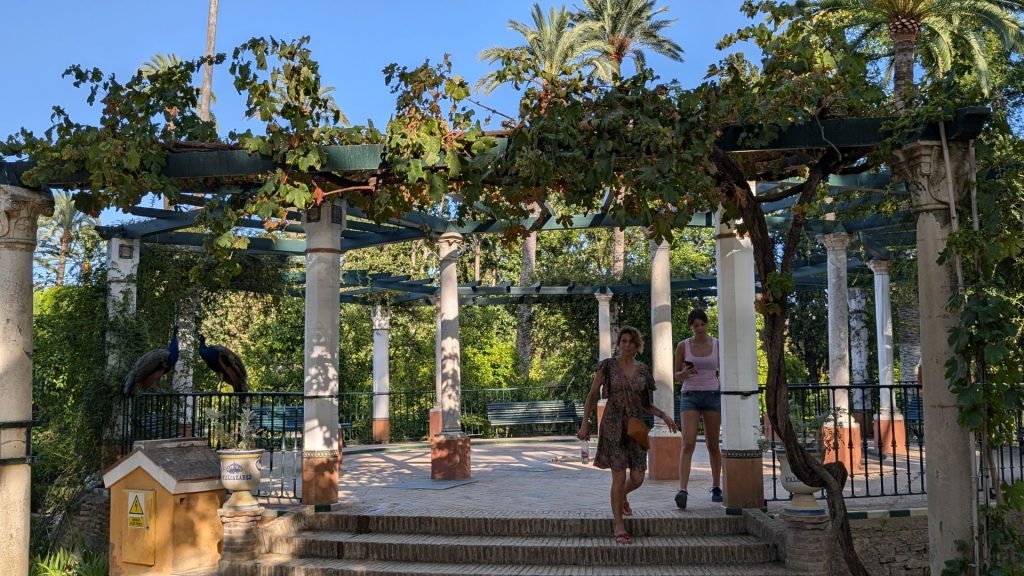

And there are peacocks! Just roaming around.

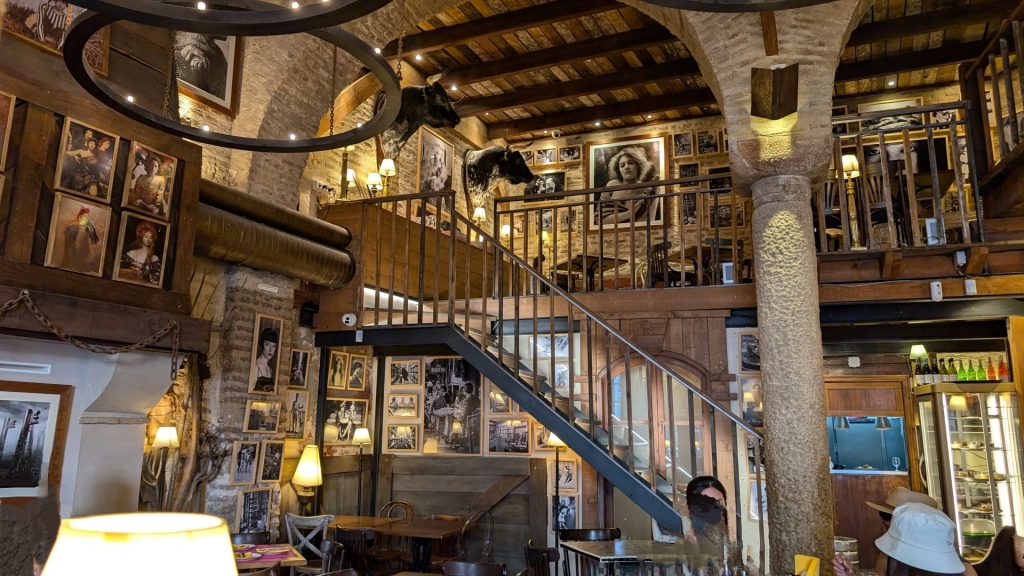

We found a great place for dinner! Fantastic tapas and a great atmosphere!

We’ll share information and pictures about our second day in Seville in the next post.