We said goodbye to Cathie and Greg the night of the 17th. They were headed to Iles de la Petite Terra and we were headed back to the mooring ball.

We returned the rental car on the 18th and I took myself to a little nearby cafe. I wasn’t sure what I was ordering for a pastry but I figured it would be good no matter what it was. I posted the “mystery” pastry on Facebook and my worldly friend, Jayne, knew what it was immediately. It is a chausson aux pommes, which is kind of like an apple turnover.

The other guests and I were “serenaded” by this guy (the big guy on the right):

I continue to pay attention to the flowers. I rarely know what they are, but their mere presence makes me happy.

February 19

I decided to go to Pointe-à-Pitre on the 19th to visit the Memorial ACTe Museum.

Pointe-à-Pitre is the place to go if you want to buy discounted French wares such as perfumes, scarves and cosmetics. (I didn’t.) It is also Grande-Terre’s largest city and where the cruise ships stop. It is where you will find the Marche Couvert, a vibrant marketplace where they sell aromatic spices, food and locally woven fabrics.

This fountain next door to the market is pretty. Apparently it is just a fountain without symbolism, at least nothing I could fine. But I like it.

This statue is of Marcel Lollia, known as “Vélo.” It was erected on June 5, 2004, to commemorate the 20th anniversary of his death. The bronze statue, created by artist Jacky Poullier, is an initiative of the Akiyo cultural movement. The sculpture consists of a stone base with a representation of Vélo. He is seated with his ka between his legs and his hands on this ka.

Marcel Lollia (1931-1984)

Marcel Lollia, known as “Vélo” (1931-1984), was a Guadeloupean “master tambouyé” (drummer). He was initiated by the “master tambouyé” Carnot and made his debut in Point-à-Pitre. He later became a respected ka player and opened a school dedicated to this instrument. He was also one of the founding members of the Akiyo cultural movement.

The Ka

The drum, Ka, was a communication tool for slaves and is at the origin of the creation of the musical genre “Gwo ka”, inscribed since 2014 on the UNESCO Representative List of Intangible Cultural Heritage. This genre combines responsorial singing in Guadeloupean Creole, dance and the rhythms of the ka drum. The participants and the public form a circle in which the dancers enter in turn, facing the drums

But I was primarily interested in visiting the Memorial ACTe Museum. The museum is located on the site of a former sugar factory. This cultural center is part of UNESCO’s Slave Route-Project, a global initiative that aims to explore the causes, forms of operation, stakes and consequences of slavery in the world. Though France abolished slavery in its colonies (of which Guadeloupe is one) in 1848, it wasn’t until 2015 that the Memorial ACTe debuted. With the help of art installations and multimedia displays, the museum chronologically explores the evolution of the slave trade in the Caribbean, starting with Christopher Columbus extending all the way to modern-day slavery and trafficking across the globe.

A brief history of slavery in Guadeloupe from https://www.cipdh.gob.ar/memorias-situadas/en/lugar-de-memoria/memorial-acte/:

“At the beginning of the 17th century, France conquered the Guadeloupe archipelago, located in the Caribbean Antilles. During the first years, the French Government granted the administration of the territory to the Company of the Islands of America, which was in charge of distributing the lands to the French settlers so that they could develop sugar cane, tobacco and cocoa plantations. In the mid-17th century, thousands of people were transferred to be used as slave labor. Sugar cane production became the predominant crop in the archipelago and the population began to grow as the plantations prospered.

Between 1759 and 1763, as part of the Seven Years’ War, Great Britain occupied Guadeloupe and moved 15,000 people to work as slave labor on plantations. In 1763, the French regained control of the archipelago, which became a strategic territory due to its location and the growth of sugar cane production. The plantation economy, based on slavery, servitude and the exploitation of people, generated large profits for the colonizers. As sugar production grew, more enslaved people moved in from Dutch and French colonies in the Caribbean or on the African continent. In 1790, 90,000 enslaved people lived in Guadeloupe, representing 85% of the total population of the island.

In the context of the French Revolution of 1789, the news of the approval of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen generated revolts in the Antilles that were repressed by local governments. The French republican authorities continued to maintain the legality of slavery in their colonies. On April 20, 1793, a rebellion began in Guadeloupe when hundreds of slaves from various plantations used weapons given to them by monarchist planters to fight against the republicans, killing 23 colonist citizens. Subsequently, the rebel group was imprisoned and the republican authorities reinforced surveillance on the plantations.

At the beginning of 1794 the British invaded Guadeloupe again and in 1802 the troops of General Richepance under the orders of Napoleon Bonaparte, landed on the island, regained control of the territory and maintained the slave system. Slavery was definitively abolished in Guadeloupe in 1848, when the French Second Republic approved the decree abolishing slavery in the French territories and its colonies.

Since 1946, Guadeloupe had been part of the French overseas departments. It is governed by two councils, one general and one regional, whose authorities are elected by the Guadeloupean population.”

To read more about the museum, check out this link: https://www.tribes.org/web/2017/3/6/a-visit-to-the-memorial-acte-in-pointe-a-pitre-guadeloupe

Although the interior is where all of the information is found, the exterior is a sight to behold.

I walked around the entire exterior before entering. I happened upon a cool tree full of pods:

Let’s go inside. I don’t have a lot of pictures to share. I mean, I took a lot of pictures, but I think the art installations are the best for sharing.

ALERT: The Memorial ACTe Museum is about slavery. This is not a “cheerful” topic. Therefore, this is not a “cheerful” post. I invite you to read this because it is important for all of us to know the history. That said, it will not be pleasant. If you decide to forge ahead, please do so with this in mind.

For those who are still with me, here we go, in the order in which items are presented in the museum.

Below is a picture of La Voleuse d’enfant (The Child Grabber) 2010-2015. This is the description:

“Is black a color? Guadeloupean artist Thierry Alet may have asked himself this question, which undeniably conjured up memories of slavery. Nonetheless, rather than quibble over academic matters he chose to use the palette of colors at his disposal to shift the burden of proof, shatter conventions and, like Gissant and his nation of an ‘All World,’ establish an ‘all color’ world as new dogma. He studied at the Institut régional d’art visuel de Martinique in Fort-de-France, and has a Masters degree from Pratt Institute in New York.”

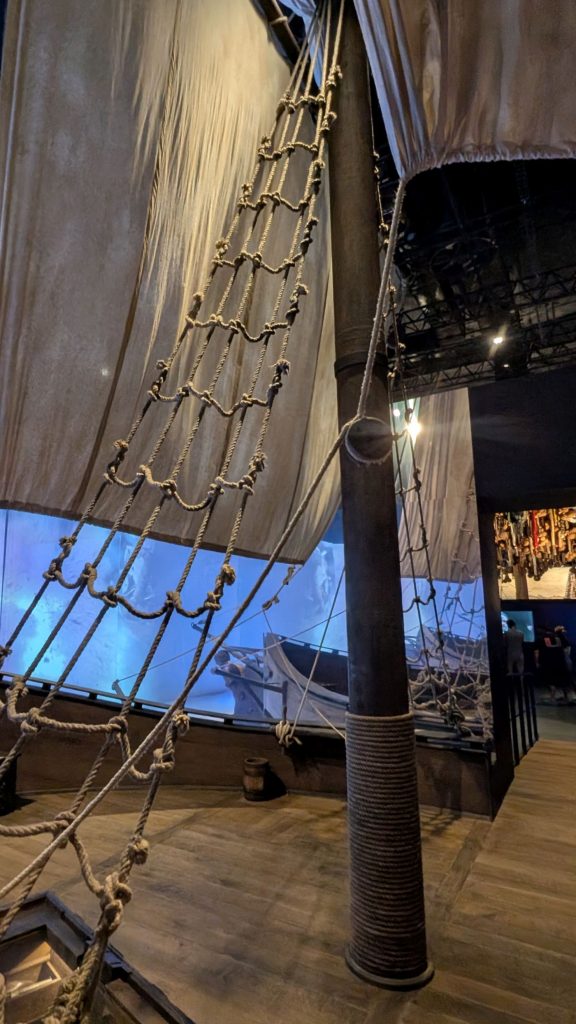

This next one isn’t actually art work but it is a multi-media display that I thought was artfully done. It is a display about piracy. The visitor is located on the ship that is being pirated. The video and audio display is of the pirates. The sign reads as follows:

“Records of piracy go back to Ancient Mediterranean times. Corsairs or privateers received orders and commissions from a European king. Pirates or freebooters worked alone. Although the tradition disappeared in the Caribbean Sea at the end of the 19th century, piracy remained in different forms and still exists today.”

Piracy and slavery were closely linked, with pirates capturing and selling slaves, and using slave ships to further their own goals. Pirates liked slave ships because they were fast and could carry large numbers of people.

Pictured below is L’Arbre de l’oubli (Tree of Forgetfulness). 2015 Description:

“Before they were loaded onto ships, captives were made to circle the ‘Tree of Forgetfulness,’ a ritual that would force them into an artificial state of consciousness to make them forget their past lives. Pascale Marthine Tayou’s depiction is a magical, mighty Nature’s tree, bearing the cultural tokens and religious symbols slaves could not take on their voyage. Born in Cameroon in 1967, Tayou has divided his time between his homeland and Europe for the past 20 years. Aesthetically pleasing, his work explores African archetypes and Western art references; it has been exhibited in some of the most prestigious museums such as the Louvre and at the Contemporary Art Museum in Lyon in 2011.”

I neglected to capture the artist’s name and the description of the following artwork, although the work tends to speak for itself, so a description is probably unnecessary.

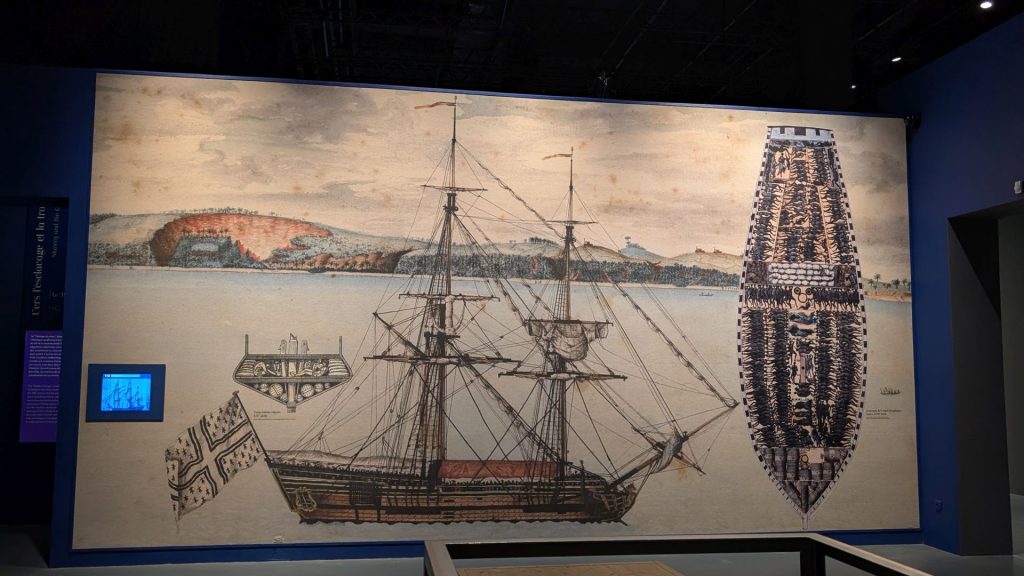

Pictures below: a slave ship. Near this display was information about “A dynamic triangular system,” that was uber disturbing and horrendous.

“. . . the commerce is generally known as the triangular trade, since that best conveys the European profit-based nature of trade. A typical business model would involve an entrepreneur in London or Nantes who chartered a ship and loaded it with merchandise whose value was particularly high on the African coasts but lower in Europe. The Africans paid for those manufactured goods with slaves, who were then transported across the Atlantic and sold in the American Colonies or traded for colonial products. Those products then increased in value when shipped to European markets. So by sending ships via Africa, European entrepreneurs could increase the return on their original investment twice. The model can be represented in a more concrete way as glass trinkets for slaves; slaves for tobacco and cotton; and finally tobacco and cotton for gold – so glass beads for gold. However, this standard description does not cover some of the basic characteristics of the transatlantic slave trade: the need to assemble slaves at a few points on the African coasts and the difficulty of doing so; the sugar boom in the 18th century and its consequences; the exponential growth of the African slave trade and the variety and real value of products exchanged with Africa; the division of the slave trade into two major systems, north and south; and finally the extent of the direct traffic between Africa and the Americas.”

The artwork pictured below is Enreponts or Between decks, by Pablo and Serge Sastillo. 2015

The sculpture “Entreponts” was designed for the ACTe Memorial and made exclusively of ceramic. Highlighted by two display cases exhibiting goods worthy of exchange in the triangular trade system, the sculpture “Entreponts” denounces the objectification and commodification of humans by capital. It questions the place of Man as “good” or “wealth” and the relevance of a system based on such an aberration. With a contemporary look, its deliberately cubic aspect is a reference to containerization and maritime trade. “Entreponts” also functions as a core sample of a slave ship, thus restoring all its horror.”

The picture below is of an evolving video display so I am not sure I caught all of it, but I think I did. These are slave trade routes.

A couple of signs near this contain the following information:

“In the span of three centuries, between 12 and 13 million black African were victims of the transatlantic trade. Portugal and its Brazilian colony was the largest power of the slave trade and shipped over 5 million, England came second, followed by France, Holland and Spain. Although the Transatlantic slave trade spanned several centuries, it was at its peak during 1740 and 1850 during which 90% of the slaves were deported. Not a destination on the regular trade routes, records show only 108 ships and 22,3357 slaves arriving in Guadeloupe directly from the French trade. 33,500 others came from the English trade. Shady or clandestine trade numbers are not accounted for.”

And. . .

“The Middle Passage makes reference to the Atlantic crossing of slave ships between the beginning of the 16th century and the second half of the 19th century. Slave expeditions being costly, ship owners worked with associates and stockholders. The trip across the Atlantic lasted four to 15 weeks depending on the chosen route and the weather conditions. The French transported an average of 320 individuals per ship, two-thirds were male and more than a fourth were children. Slave traders took advantage of mandatory quarantine off the coast to make survivors look presentable.”

The very disturbing display pictured below shows the weapons used on the slaves. These quotes accompany the display:

“The whip belongs to the colonial system, the whip is the main actor; the whip is the soul; the whip is the bell of houses, it says when it’s time to wake up, time to retire; time to work; the whip also indicates when it’s time to rest; and to the rhythm of the whip the guilty man is condemned, the people of houses gather for the morning and evening prayers; the day a nigger dies is the one and only when he discovers the oblivion of life without the awakening of the whip.” Victor Schoelcher, Abolition Immédiate de l’Esclavage, Paris, Pagnerre, 1842, p. 84. (English translation of title: Immediate abolition of slavery)

“The ‘rigoise’ is a kind of long and thick crop, made of ox nerves, wrapped around or stretched together. Handled with strength, the rigoise could break a limb. The house-bullwhip is heavy, on the contrary, the commander or master can hold a rigoise in his hand. It’s easy to hide it or to justify its presence. It’s a useful tool, one brings it to work.” The Attorney General of Guadeloupe in Adolphe Gatine’s Du progrès aux colonies, Paris, Ph. Cordier, February 1848 (The full title, translated to English: From progress to the colonies. Regarding a judgment of the court of Guadeloupe…)

Freemasonry (related picture below) held an important role in the abolition of slavery. However, in the Antilles, Blacks and people of mixed race were not readily accepted. The first freemason lodge was established in 1745. Starting in the 1820’s, more progressive rules supported the abolitionist movement. Banned from the Antillean lodges and initiated in Paris, some men of mixed race decided to found their own. Some of these pioneer organizations played an active role in abolition and the education of newly freed individuals.

The display of drums (below) is described as follows:

“At the crossroads of multiple African influences, the drum is heir to the slaves’ social struggle and cultural resistance. Slaves maintained their beliefs based on rich musical heritage and often expressed during rituals through song, dance and rhythm specific to various cults of possession throughout Africa.”

Alert: Slam on the Catholic Church to follow.

“Since the beginning of colonization, the Catholic Church has claimed to guarantee the moral and spiritual aspect of the conquest. Endorser of slavery, Catholic religion was the path to redemption for Native American and African ‘idolaters’ and an official means to control and rationalize economic and territorial conquest. Firm believers in education and baptism, the missionaries held that non-Christians—Native Americans or Blacks deported from Africa—had no religion but rather deviant beliefs or occult practices that should be rooted out. Animists and Muslims were converted and instructed according to Catholic dogma, in the manner of slaves who were already Christians.”

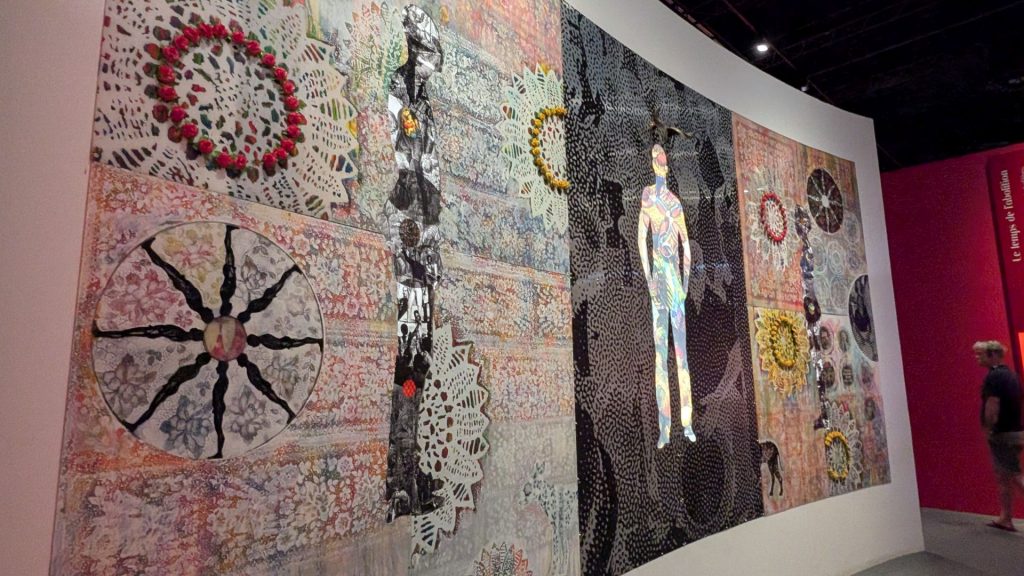

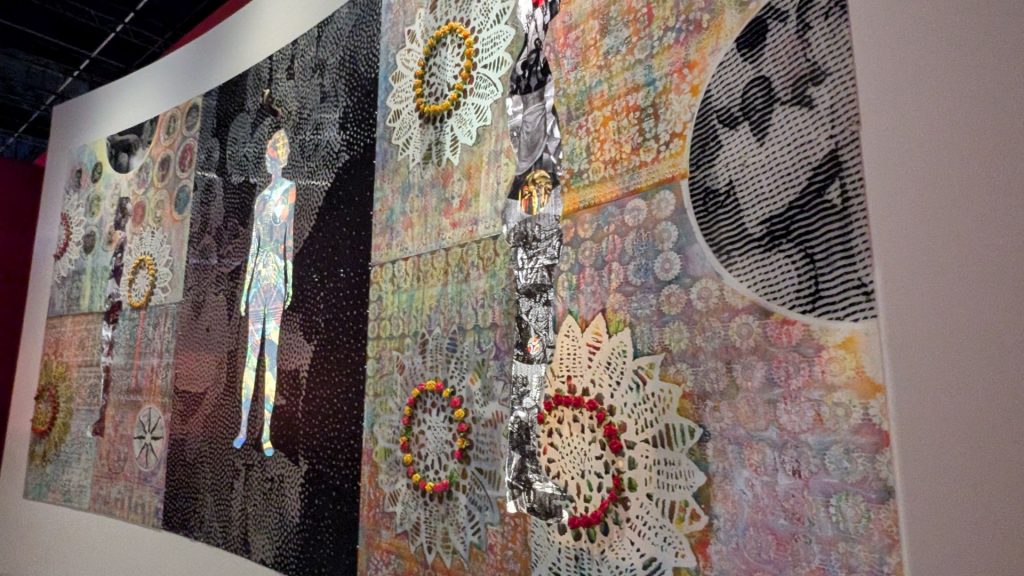

The three very colorful pictures below are festive, right? Here’s what the museum had to say about this exhibit:

“On the sidelines of the burlesque, carnival-like parties and receptions hosted by the colonists, slaves organized supportive, clandestine kingdoms called ‘nations’ or ‘convoys,’ thus making an essential contribution to today’s popular carnivals. As early as the first decades of colonization, slaves originating from the same region came together for festive gatherings. In the mid-18th century, these congregations abided by the catholic calendar and took advantage of holidays to get together privately or publicly. A number of these ‘nations’ became creolized, encouraged mutual assistance between their members, and held ceremonies in which their secret rituals celebrated the ‘mysteries of the Black Continent.'”

As noted toward the beginning of this post, slavery in Guadeloupe was officially reinstated by Napoleon Bonaparte in 1802, after it had been abolished in 1794 following the French Revolution. The reinstatement of slavery is the theme of this next piece of artwork, called Révolutions (Revolution). Description:

“For Bruno Pédurand, like for all Guadeloupeans, the reinstatement of slavery remains an open wound. The artist’s installation in the convex shaped hallway stirs up memories. Visitors enter a haunted world in which symbols of past and present are intertwined. With human beings at its core, the general shape of the layout is reminiscent of a ship’s hold or belly. The ship however, is not headed for the despised cotton fields but instead sails toward newfound liberty, a value that is now up to us to defend in order to be worthy. Born in Pointe-à-Pitre in 1967, Pédurand holds a degree from the Institut régional d’art visuel de Martinique.”

The red, yellow and black artwork below filled the room. It is L’Histoire en marche (Historical Footsteps) by Shuck One. 2015 Description:

“Based on a map of Guadeloupe, this three-dimensional artwork traces the battles’ topography including a chronology of the conflict through collages. As one follows in the footsteps of the freedom fighters, their path takes on realistic and physical dimensions. As one of the first generation of French graffiti artists, Shuck One has mainly worked on canvas since the early 1990’s. Although personal artistic expression is essential, his work, above all, is about the social and cultural empowerment of the individual beyond any borders.”

I should note that the museum also highlights the stories, struggles, challenges, defeats, successes, etc., of many freedom fighters and their supporters. There just wasn’t any artwork I can share with you. This type of info was presented primarily via multi-media displays and plaques.

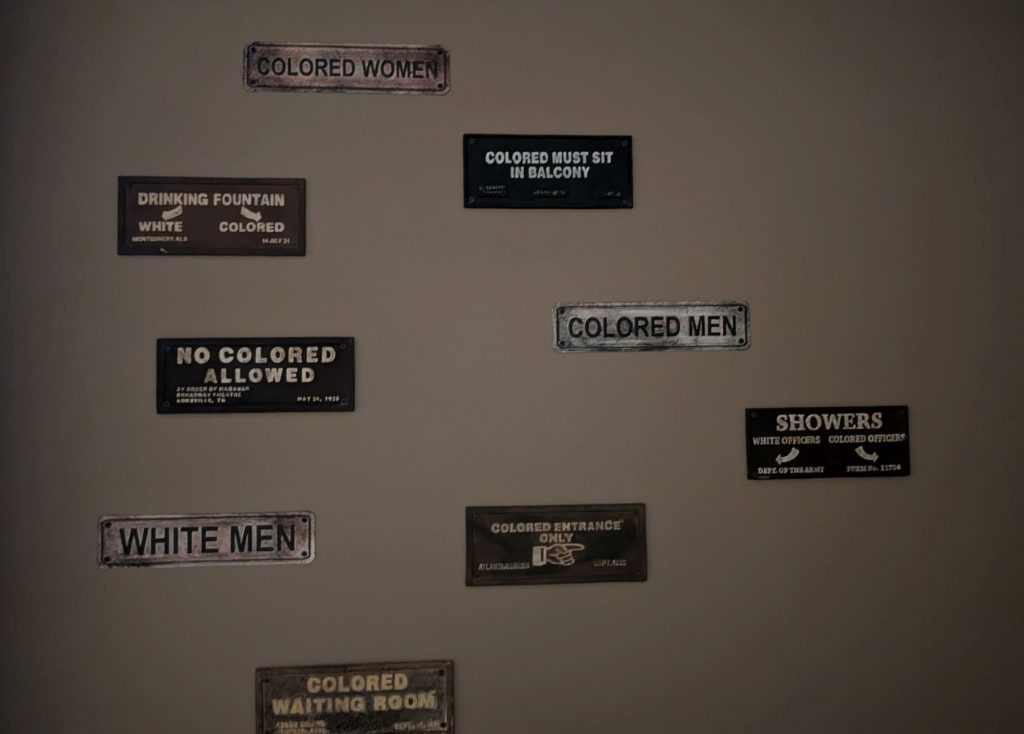

We are moving to a more recent history now, which includes the horrible KKK and other overt forms of oppression and racism in the USA.

If we are tempted to think that slavery has been abolished world-wide, we need to think again. Although the alienation of liberty and slavery are not new phenomena in the history of humanity, their scope is unprecedented in the 20th and 21st centuries. Still today, millions of people throughout the world endure different forms of subservience: traditional slavery, child labor, domestic servitude, organ trafficking, sexual slavery. . .

Happy thoughts in the next post. I promise.