We got to Cork in mid-afternoon on the 1st and went to a pub planning to have a pint. We ended up enjoying the company of the bartender and patrons so much that we stayed for another pint and dinner. That was our first day in Cork! It was nice to have a relaxing afternoon. We’d been traveling for about three weeks by this time and kind of needed it.

Our hotel in Cork:

We headed out on the 2nd for a day of sightseeing. Our goals were to see St Fin Barre’s Cathedral, the Elizabeth Fort, Saints Peter and Paul’s Roman Catholic Church, and the Cork City Gaol. And we did!

We passed by this interesting building (below) early in the day. I later learned that it is the Crawford School of Art. A school of art should have a pretty building.

We also passed by this building (the two pictures below), the St Marie de L’Isle (St Marie’s of the Isle), a convent of the Sisters of Mercy. They arrived in Cork in 1837 and established a school for the deaf in 1858. Then a Mr. Meehan, on behalf of the community, bought the land on which the school now stands for £375.

The building of St Marie’s of the Isle Primary School started in May 1891 and was placed under the patronage of Our Lady of Good Counsel on completion. By August 1892, the classrooms were organized and all was in order to start work.

The first addition to the school came in 1928 when Rev. Patrick O’Toole blessed the new wing known as “The Terrace” which provided four additional classrooms, cloakrooms and toilets. Electric light and central heating were also installed at this time and the playground was enlarged.

The Convent acquired a large yard adjoining the school from Messrs Beamish and Co. on December 7, 1936, for which they paid £800. At this time 12 new classrooms, cloakrooms and toilets were added and corridors were added, meaning a visitor did not have to walk through every classroom. It is still a primary school today.

Here is a short article from The Building News, December 7, 1850.

So those were two unexpected fun finds. But now we pursued our sightseeing goals.

St Fin Barre’s Cathedral

The patron saint of Cork, Saint Fin Barre, gives his name to this cathedral. According to tradition, he lived at an island hermitage at Gougane Barra at the source of the River Lee before founding the monastery in Cork. Regarded as the first Bishop of Cork, his name “Fionnbarr” means “fair headed” in Irish.

The site of this cathedral dates back to the 7th century when a monastery was founded here. A succession of church buildings ensured that Christian worship continued through the centuries. Settlements around the monastery eventually grew into the city of Cork.

In about 1536, during the Protestant Reformation, the cathedral became a part of the Established Church (later known as the Church of Ireland).

In 1864, the existing small cathedral was demolished and the present magnificent structure was built in its place. This three-spire cathedral is hard to miss on the city’s skyline. And it’s French Gothic in style.

The new cathedral was consecrated in 1870, although work continued for many years.

The cathedral was designed by William Burges, an avid follower of 13th century French Gothic architecture. He designed every part of the building including the stained glass windows and 1,260 pieces of sculpture. The cathedral has a wealth of detail, symbolism and high quality design.

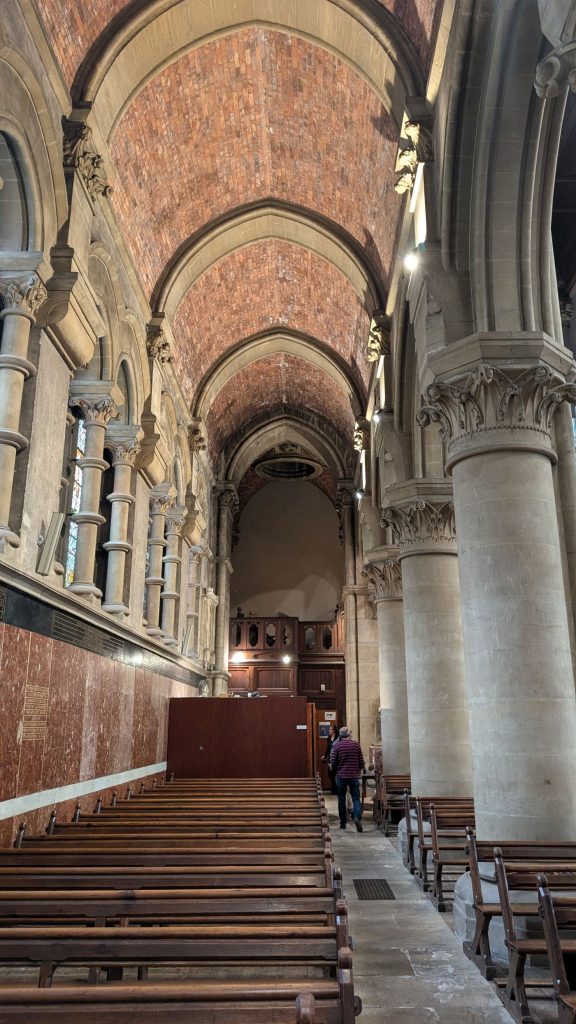

Interesting features include the high columns of the nave made of Bath stone. The walls are lined internally with Cork Red Marble. The iconographic scheme deals with the journey to the new Jerusalem and some of the best stained glass in Ireland show scenes from the Old and New Testaments. The organ, dating from 1889, is placed in the north transept. It is the largest Cathedral Organ in Ireland and the only one in a pit in Britain or Ireland. There is a cannonball dating from the siege of Cork, 1690, which we somehow managed to miss. 🙁

Here are a few pictures of the exterior. So beautiful!

Cathedral Organ

The organ was built in 1870 by William Hill & Sons. It consisted of three manuals, over 4,500 pipes and 40 stops. It was in place for the cathedral’s grand opening on Saint Andrew’s Day, 1870, and positioned in the west gallery, but moved to the north transept in 1889, to improve acoustics, maximize space, and avoid its interference with the view of the windows. That year, a 14-foot pit was dug in the floor beside the nave, as the new location for the organ.

Its maintenance has been one of the most expensive parts of the cathedral’s upkeep. It was overhauled in 1889 by the Cork firm T.W. Magahy, which added three new stops. The next major overhaul was in 1906 by Hele & Company of Plymouth, which added a fourth manual (the Solo). By this stage, the action of the organ was entirely pneumatic. In 1965–1966, J. W. Walker & Sons Ltd of London overhauled the soundboards, installed a new console with electro pneumatic action, and lowered the pitch. (This paragraph was included for those who understand organs.)

By 2010 the organ’s electrics were unreliable. Trevor Crowe was employed to reconstruct and increase the number of pipes, and make tonal enhancements, including a 32′ extension to the pedal trombone. The project cost €1.2m and took three years to complete.

Stained Glass Windows

Seventy stained glass windows tell the Bible story, in 150 scenes, from Genesis to Revelation and are among the best stained glass to be found anywhere in Ireland. Uniquely, they were crafted using a medieval technique at the insistence of William Burges. Here are some of the windows.

The Ambulatory or walkway contains stained glass windows showing the life of Christ.

The Lectern

The lectern holds the Bible which is then read aloud during services. Originally designed by William Burges for Lille Cathedral, this lectern was presented by the women of Cork. It is made of solid brass, weighs 900 pounds (408 kilos) and is decorated with the heads of Moses and David.

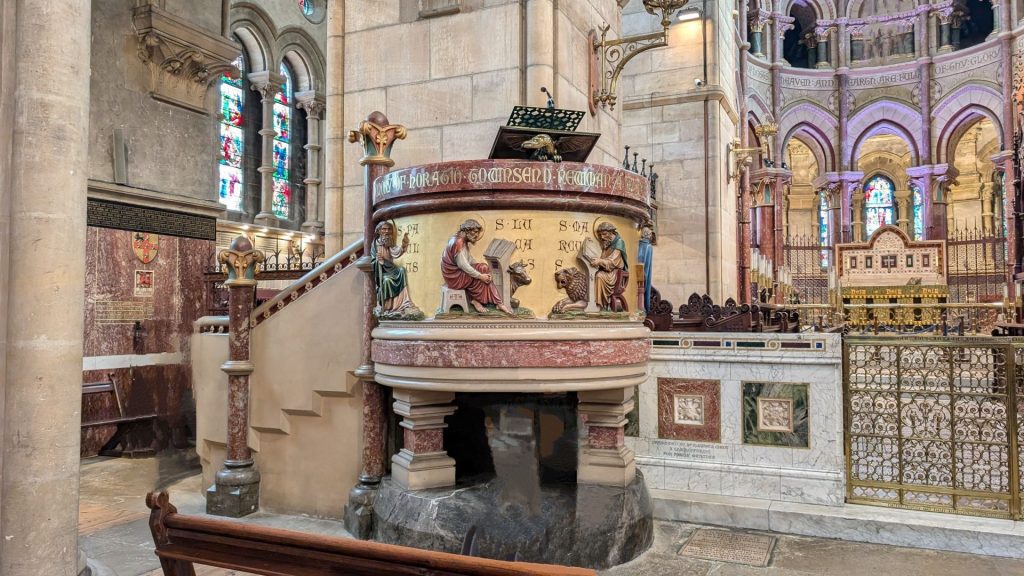

The Pulpit

Used for preaching, the pulpit was completed in 1874, but not painted until 1935. It shows the four evangelists with their symbols, together with St Paul sitting on an upturned “pagan” altar. The winged dragon beneath the reading stand (arguably my favorite part of the cathedral) symbolized evil (oops!) taking flight at the sound of the Word of God being preached. (I don’t know how such a cute dragon can symbolize evil.)

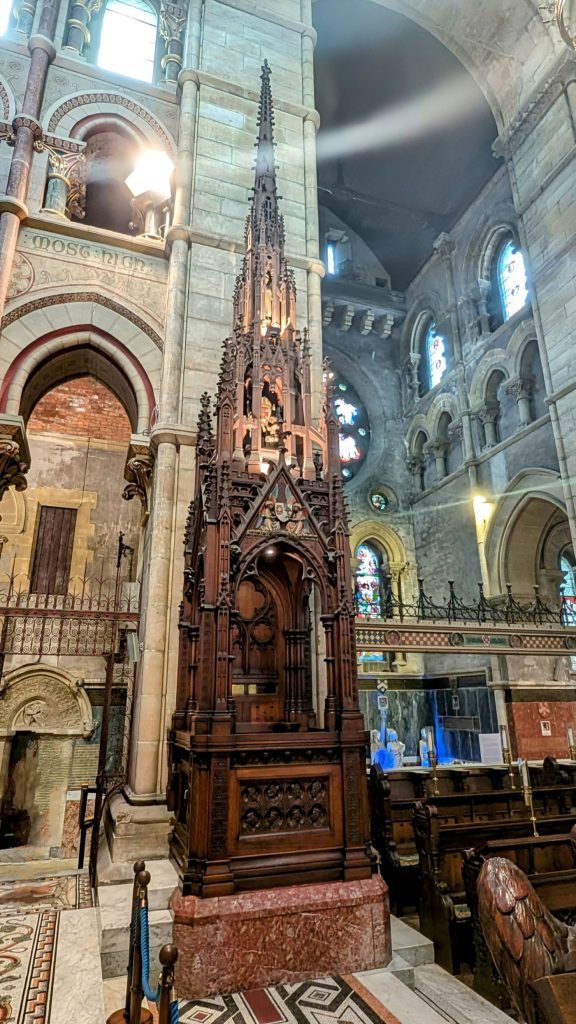

Bishop’s Throne

The elaborately carved oak Bishop’s Throne shows images of 20 important bishops of Cork around the base. It is 46 feet (14 meters) in height and near the top is a painted statue of St Fin Barre and angels holding the episcopal coat of arms.

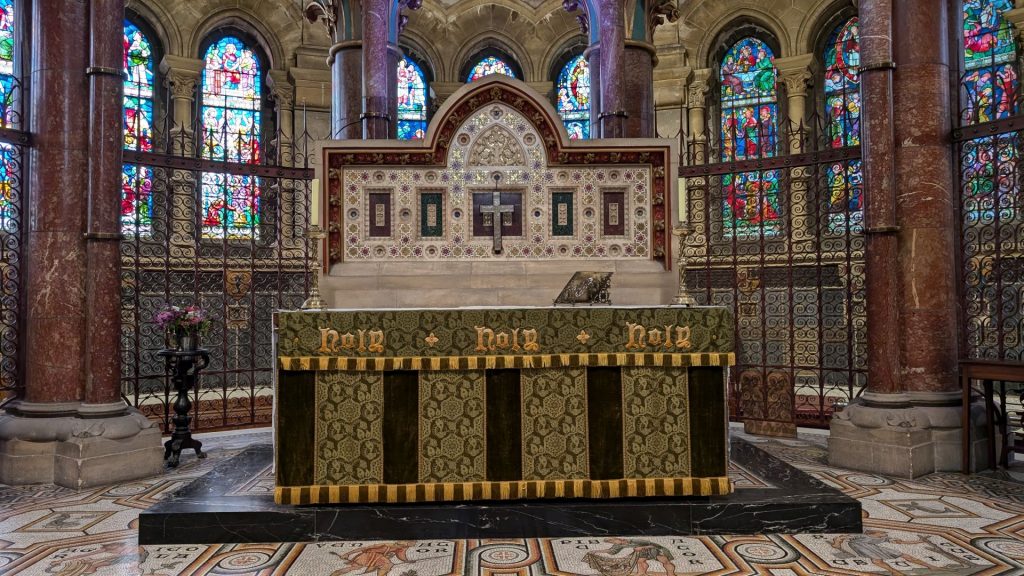

Sanctuary Ceiling

The elaborate and colorful painting on the sanctuary ceiling was carried out between 1933 and 1935, to the designs of William Burges. It is beautiful!

Other things!

Now, more than 150 years after completions, St Fin Barre’s Cathedral remains a cherished landmark, not only for its architectural magnificence but also for its significance as a place of worship and cultural importance, drawing visitors and worshippers alike to admire its beauty and delve into the history and spirituality it embodies.

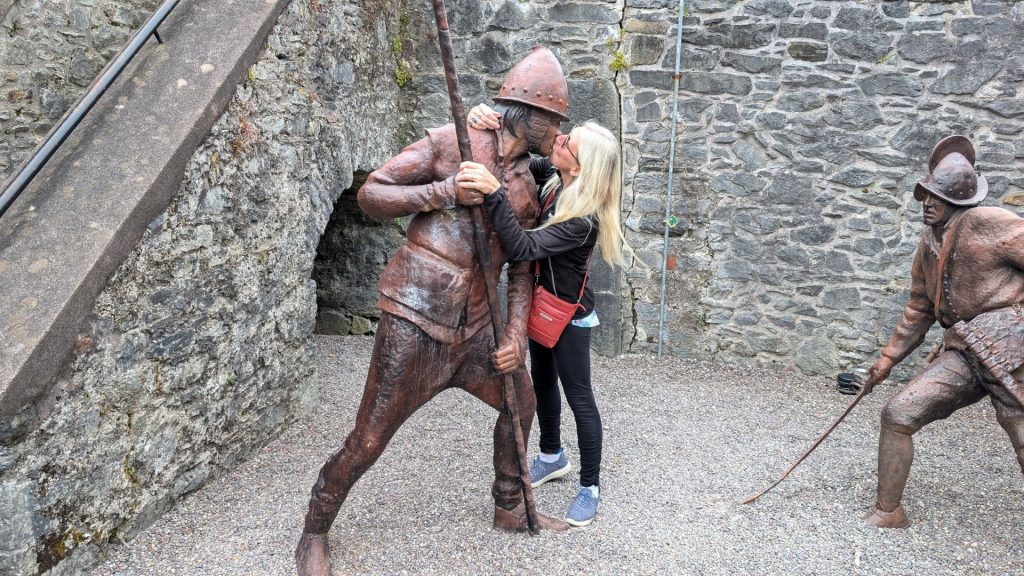

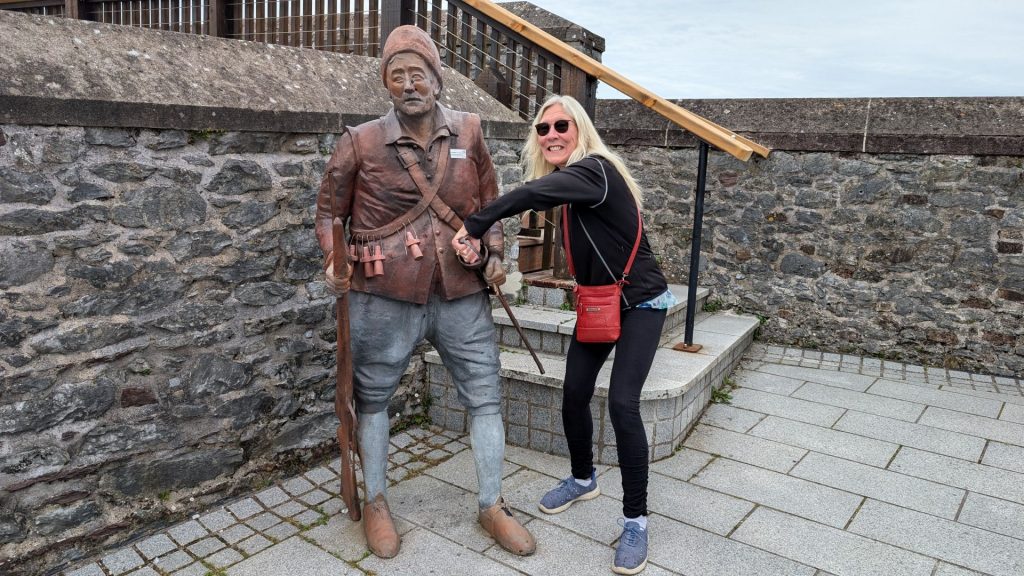

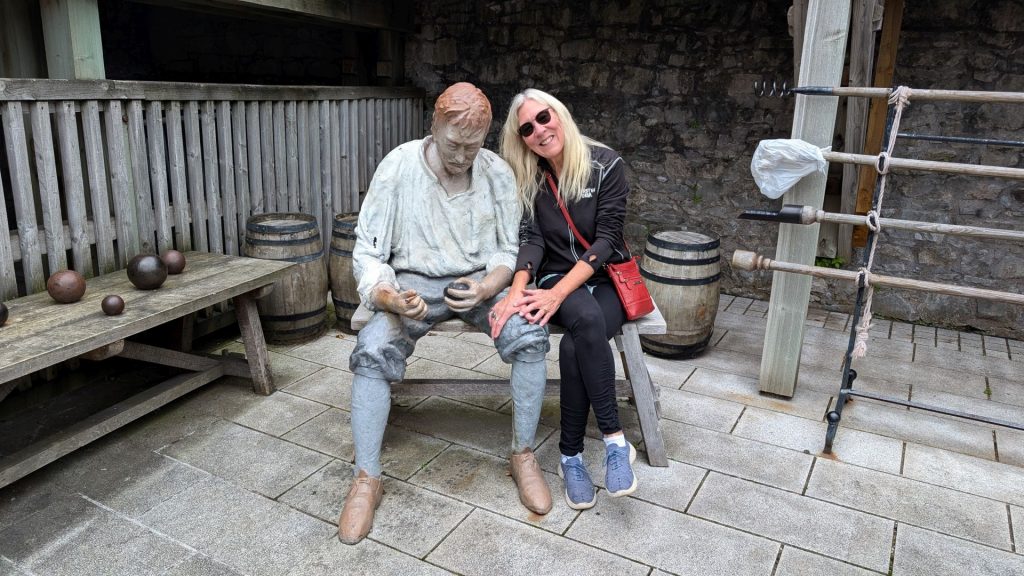

Next on the agenda was the Elizabeth Fort. Check out the brief history here https://www.corkcity.ie/en/elizabeth-fort/history/. Assuming you will do that, I’ll just share a few of the highlights.

The Fort has played a hugely important role in Cork city since the 17th century. Two years after the building of the fort, it was attacked by the people of the city. It was also one of the focal points of the Siege of Cork in 1690. It was also used as a convict depot for prisoners awaiting transportation to Australia, a food depot during the Great Famine and until recently, a police station.

We spent most of our time amusing ourselves.

Our penultimate visit was to Saints Peter and Paul’s Roman Catholic Church.

Constructed in the mid-19th century, this awe-inspiring church boasts a stunning façade adorned with intricate Gothic-style details. Its towering spires and grand entrance draw the attention of passersby and invite all to explore its sacred interior.

Architecturally, it is one of the finest churches in the city. The foundation stone of the church was laid on August 15, 1859, and the church was dedicated for worship on June 29, 1866. It replaced an older church, built in 1786, which was entered from Carey’s Lane and known as Carey’s Lane Chapel.

The prime mover in the building of SS Peter and Paul’s was Archdeacon John Murphy . He was a member of the wealthy family of brewers and had a most unusual early career for a future priest as he had worked for a time as a fur trader with the Hudson Bay Company in Canada. E. W. Pugin, a noted architect of the time, designed the church. Pugin’s father, Augustus Pugin, was largely responsible for the revival of the Gothic style in architecture. The high altar was designed by C. C. Ashlin and executed by Samuel Daly. It was consecrated in August 1874. In 1875 a new pulpit, again designed by Ashlin, and sanctuary stalls were added.

Here are several pictures of the gorgeous interior of Saints Peter and Paul’s Roman Catholic Church.

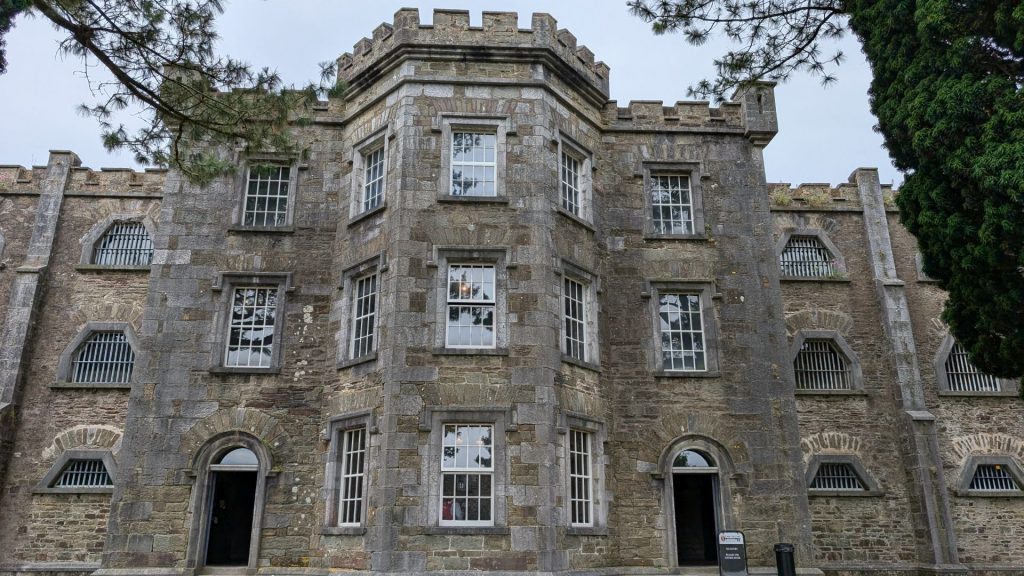

Cork City Gaol

It was time to go to jail!

Cork City Gaol opened in 1824, replacing the old gaol at North Gate Bridge. Before modern gaols like these were built prison life was dreadful to the point of barbarism. Gaol conditions began to change for the better at the turn of the century due to the new prison reform movement. In time, a more civilized system evolved with consideration for hygiene and moral improvement.

Cork City Gaol is a fascinating museum housed within a former prison, providing insight into Cork’s penal history through immersive exhibits. Visitors get an insight into what life was like in a 19th Century prison. They can explore the grounds, wander the corridors and even get locked into a cell in the prison that Countess Markievicz called “the most comfortable jail” she had ever been in! The gaol shares the stories of some of the prisoners and staff that resided here like Mary McDonnell, who became a regular at Cork City Gaol with no less than 57 convictions! Or the amusing story of conman James Burns and how he nearly slipped arrest.

Are you ready? Here we go! Let’s start with some pictures of the exterior.

Let’s meet some of the staff and prisoners. We met more than I am sharing here, but I think these are some of the more interesting cases.

Mary Sullivan

The first prisoner we met was Mary Sullivan, who was waiting to see the governor. The governor interviews every prisoner upon admittance, after they have been deloused according to prison regulations. During each meeting he records their height, weight, hair and eye color, age, and the details of their crime.

Mary, who is being escorted by a female warder, is a seamstress by trade. In 1865, following her eighth conviction she received a seven year sentence for the theft of cloth – an unusually long sentence for the crime. Prisoners with long sentences were regularly transported to Australia, as this cost less than housing them in the gaol.

The Governor’s Office

In the governor’s office sits Governor John Barry-Murphy at his desk, engrossed in his papers. He governed here between 1856 and 1873 and was the first Irish Catholic appointed to the office. During this time the British policy of appeasement resulted in Irish Catholics being appointed to important state positions.

His annual salary was £250 plus accommodation, food and fuel which was quite good by 1860s standards. He had a staff of 23, employed in various roles at the gaol.

West Wing

(No, not The West Wing TV series.) The western wing was remodeled during the 1870s into a brighter, more spacious double-sided cell wing. This gallery was used for Sunday worship where prisoners lined the railings on the landings.

Cell Lighting

There are openings between the cell walls. Gas lights were placed inside them to allow light to filter into two cells at the same time.

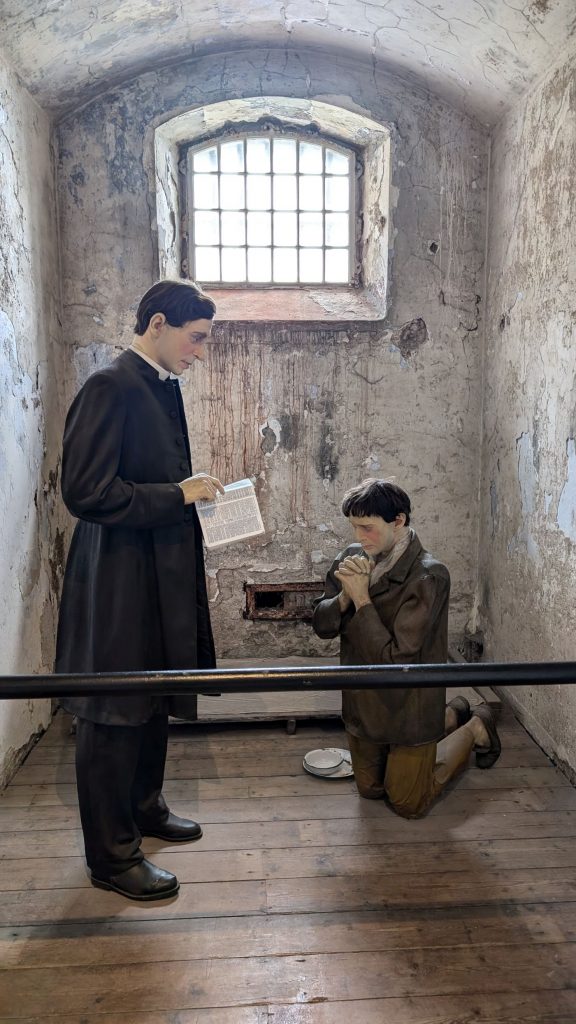

Thomas Raile

The man on his knees you see below is Thomas Raile. Convicted for stealing books and other articles, Raile is serving his four month sentence in solitude. To contemplate his wrong doing to society Raile is nurtured by religious guidance to help him see the error of his ways. He’s now praying with the protestant Chaplain Rev Nelligan but, despite this and any moral improvement which the gaol can offer, it will not be enough to give him a reference for another job when he is release. He will never work again and will therefore likely be reduced to begging, serious stealing or emigration.

Cornelius Kelleher

Cornelius Kelleher is asleep in his cell. From the early 1800s onwards, every gaol inmate had a canvas mattress. These were considerably healthier than the previous straw versions. Kelleher is serving one month for drunk and disorderly behavior. He had just been released from gaol having served a two-month sentence for the same offense when he was arrested and put back inside. Cornelius is considered a notoriously bad character, but, against the wishes of the prosecutor, the Mayor of Cork decided to be lenient with him. His chores at the gaol include picking oakum through daylight hours – a common gaol labor at the time. Unfortunately for Kelleher, he will eventually be transferred to an asylum.

Mary-Ann Twohig

Meet the youngest Cork City Gaol resident and his 16-year-old mother Mary-Ann Twohig. Mary-Ann was sent here a short time before her baby was due. Just one month into her two-month sentence she gave birth to her son here in the gaol hospital.

Mary was convicted of stealing a man’s cloth cap along with some other clothing and some kitchen utensils with a plan to pawn them.

Mary was released a few days early as a result of her son falling ill.

Countess Markievicz

We will now take a step forward in time, moving on to the early 20th century. The status of the prisoner in this cell is a little different from the other prisoners.

Countess Markievicz came from the landed gentry and, inspired by her father 5th Baronet Sir Henry Gore-Booth, had a deep concern for working people and the poor.

She is here writing a letter to her sister about her cell conditions which were quite good compared with the other prisons she has stayed in. The British-born Irish nationalist revolutionary gave authorities a long list of reasons to lock her up. In June 1919 she was given a sentence of four months in Cork City Gaol for a seditious speech she delivered at Newmarket, warning her audience against British authorities.

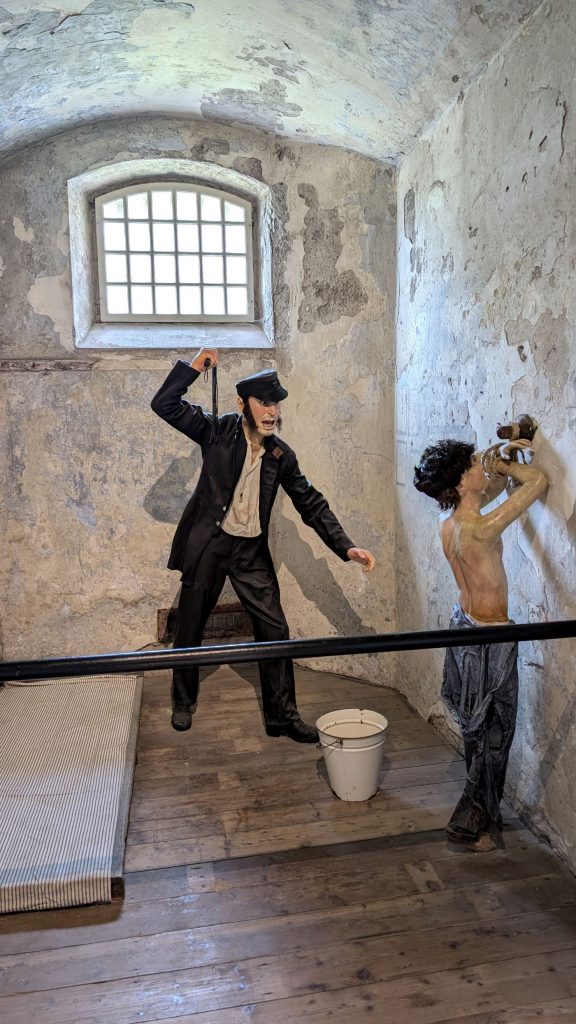

Edward O’Brien

Well known pick-pocket Edward O’Brien is serving a three week sentence with twice-weekly whippings for petty theft. This time he was caught stealing a couple of brass ball cocks.

At only nine years of age the seasoned thief already has seven previous convictions. Following his sentence at the Gaol he is to go on to a reformatory school for five years.

Cork City Gaol made attempts to provide basic schooling for children and adults while they were incarcerated. Education was later abandoned due to unsatisfactory results in the advancement of those who attended classes.

First Floor Balcony

Looking out a window just past the cell Edward was in one can see the exercise yard. Prisoners walked there in single file around a designated circle so that there could be no talking among them.

Dr. Beamish

With his medical bag in hand and accompanied by a gaol warder, Dr. Beamish hurries to attend another sick prisoner. The overworked and underpaid doctor was the sole gaol doctor. He visited the gaol at least once a day treating between 80 and 100 patients that were admitted to the gaol hospital each year. He treated a further 700 to 1,200 sick prisoners outside of the hospital out of an average gaol population of 1,400 during the 1860s. All sorts of diseases were rife including typhus fever and smallpox.

Alas, it seems the authorities placed little value on his work and when the doctor asked for a raise in salary his application was turned down.

Warder’s Room

A good game of cards beside a cozy fire in the restroom – that’s how our warders spend their time off-duty. The profession of warder, or turnkey, wasn’t held in very high esteem by society at the time. Many of the warders were only a small step away from being criminals themselves. Occasionally convicted of dishonesty or drunkenness, they might find themselves locked-up amongst the very inmates they had previously guarded.

Governor’s Tunnel

At one point, we followed some stairs down and found a closed gate under the stairs. It leads down into a dark subterranean passage. It is said that this was a secret passage for the use of the Governor and his family only, and that is tunnels underground past the gatehouse to his home across the road.

The unusual looking item at the center of the stairwell (pictures below) is a weighing scale. The governor weighed prisoners on arrival (and noted previously) and regularly during their sentence to ensure that the correct amount of food was being given to them and that no food was being stolen.

Here are some other pictures of the gaol.

Gaol Model Room

The model gives a good overview of the whole site of Cork City Gaol.

The Gaol Diet

During the 1860s the authorities of the time expected that prisoners would be given a minimum standard of food.

In Irish gaols bread, Indian mean (corn), gruel and milk were the mainstay of the prisoner’s diet. Although the more wealthy inmates could sometimes pay for alternative food to be brought in from the outside. Prisoners were given just enough food to let them carry out their work and prevent them getting sick, but not more than that. A prisoner’s diet could also be determined by the length of their sentence – for example, for those serving a short sentence milk would be replaced by the less expensive and less nutritious oatmeal gruel on the basis that he or she wouldn’t be there long enough to get really sick. Three ounces of meet were given to longer serving prisoners on hard-labor as they required more nutrition. For those held in solitary, nothing but plain bread and water is what they could expect each day.

One food that really would have improved the prison diet was the potato which is rich in vital vitamins and helps to prevent illnesses such as scurvy. Unfortunately, this period saw repeated bouts of blight, which destroyed potato crops everywhere.

Radio Museum

After the gaol closed in 1923 it was only let idle for a few years before becoming home to Cork’s first radio station Cork 6CK. We visited that museum as well but I just want to share one thing (since this post is already quite long).

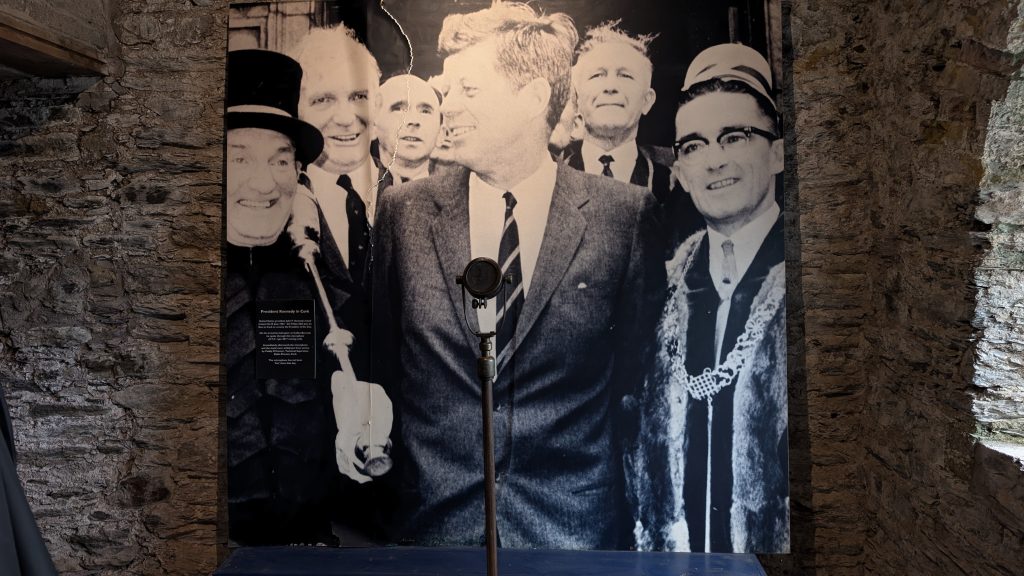

United States president John F. Kennedy visited Ireland June 26-29, 1963. On Friday June 28th he flew to Cork to receive the Freedom of the City.

On his arrival by helicopter at Collins Barracks he spoke through this microphone (S.T.C. type 41017 moving coil, for those of you who know and care about microphones).

Immediately afterwards the microphone and the stand were withdrawn from service by Paddy O’Connor, Technical Supervisor, Radio Eireann, Cork.

The microphone has not been “live” since that day.

We’d dropped off our dirty laundry earlier that day. We walked to our car, picked up the now clean laundry and headed to Killarney. Read the next post for our trip around the Ring of Kerry.