If you like Viking history, York is a good place to visit. This is primarily a (very long!) “history post.” Grab a cup of coffee before you start reading.

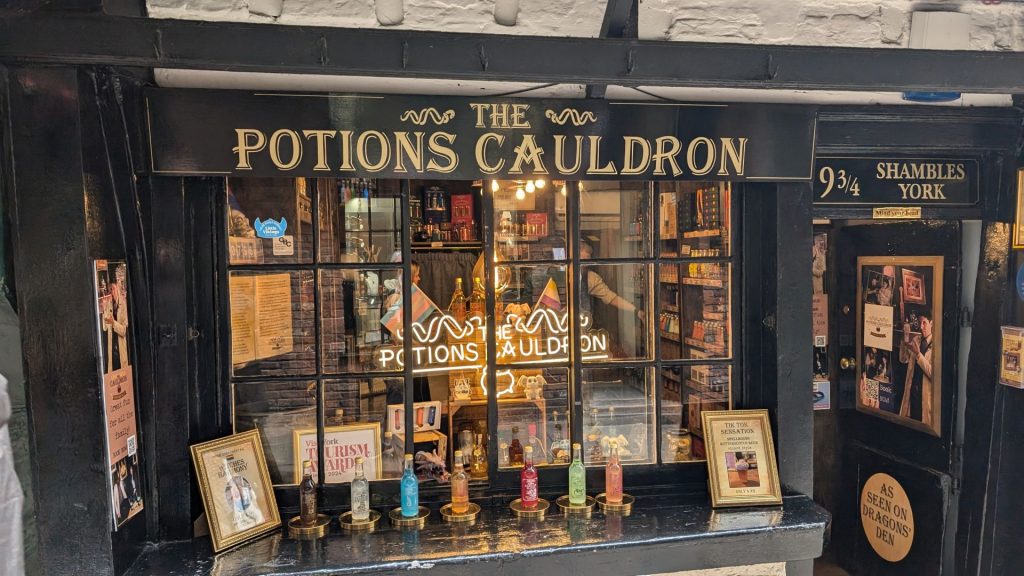

The Shambles is an historic street in York, featuring preserved medieval buildings, some dating back as far as the 14th century. The street is narrow, with many timber-framed buildings with jettied floors that overhang the street by several feet. It was once known as The Great Flesh Shambles, probably from the Anglo-Saxon Fleshammels (literally flesh-shelves), the word for the shelves that butchers used to display their meat. In 1885, thirty-one butchers’ shops were located along the street, but none remain today.

Fun shops:

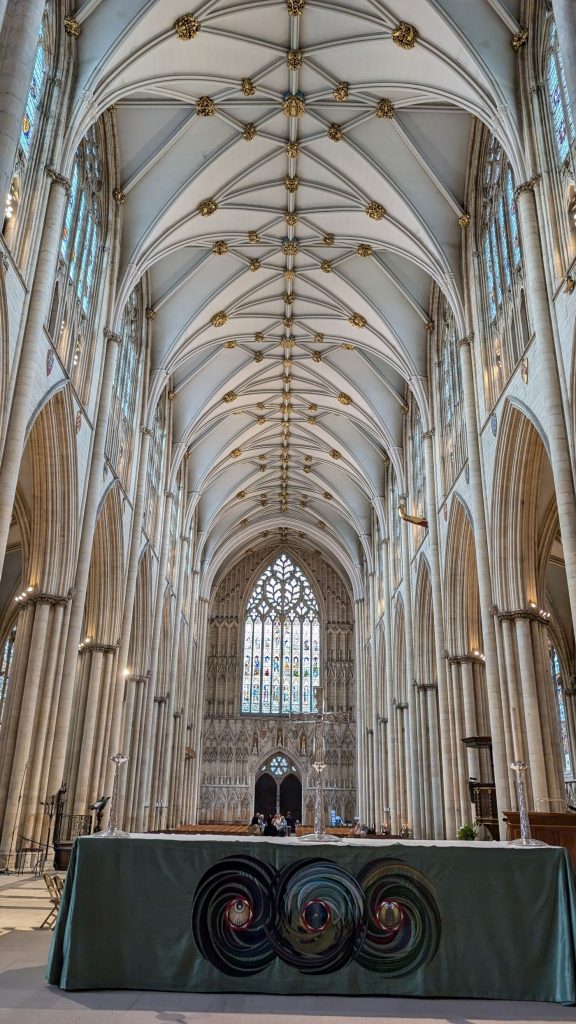

York Minster

From britannica.com:

York has been effectively the capital of the north of England for centuries, and its majestic Gothic cathedral, the biggest such structure in England, makes that stature clear. York was built at a strategic point on the River Ouse that in medieval and earlier days could be reached by seagoing ships. As Eboracum (the Roman name for York), the site was a major Roman army base and administrative center, and beneath the minster’s colossal main tower the remains of the Roman headquarters can be seen. In Anglo-Saxon times the town was an early center of Christianity. A little wooden church was built in 627 for the baptism of Edwin, king of Northumbria. This was a historic moment in England’s transition from paganism to Christianity and, according to tradition, the font in the minster’s crypt marks the spot.

The Anglo-Saxon church was soon rebuilt in stone, first in 637, and later, by 790, on a much grander scale, but the building was badly damaged when the Normans besieged and took York in 1069 and was again destroyed by the Danes in 1075. It was replaced with a new cathedral on a grander scale still.

Walter de Gray became archbishop of York in 1215 and began the rebuilding of York Minster in 1220. The project took some 250 years to complete. The minster was consecrated in 1472 when the building was at last declared finished. The twin west towers were completed by then, and the enormous Great Peter bell, installed in 1845, booms out from the northern one every day. The church was restored after serious fires in 1829 and 1840, and there was another blaze in 1984 when lightning struck the south transept. Fortunately the famous Rose Window was not severely damaged and has since been restored and strengthened.

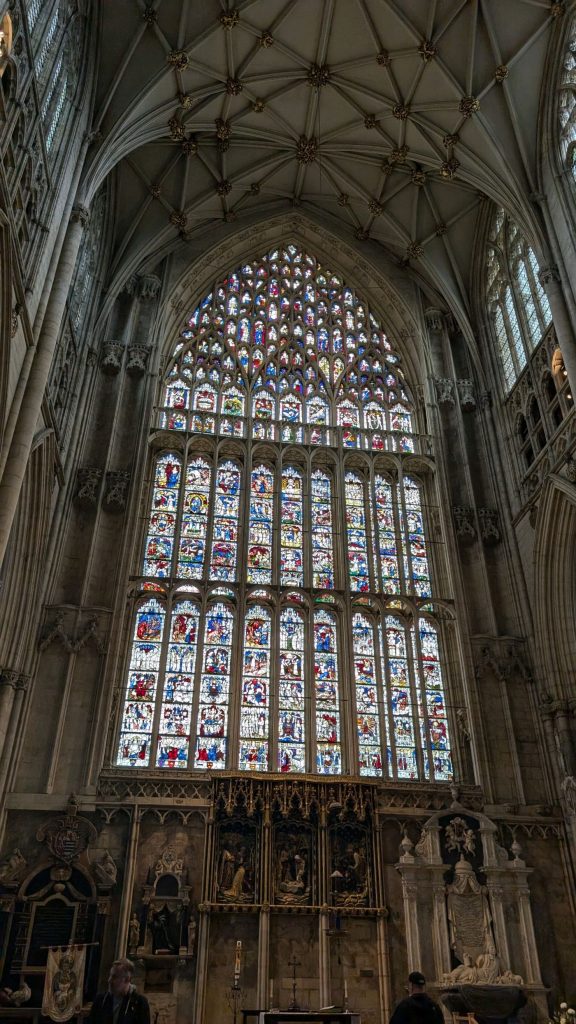

The cathedral has Britain’s richest collection of stained glass. The famous Five Sisters Window (which I did not get a picture of) is in the north transept and the Great East Window (pictured below), larger than a tennis court, is the biggest stretch of medieval glazing in existence. Executed in 1405-08, the great east window is the largest expanse of medieval stained glass in Britain, with over 300 glazed panels, and is one of the most ambitious windows ever to have been made in the Middle Ages.

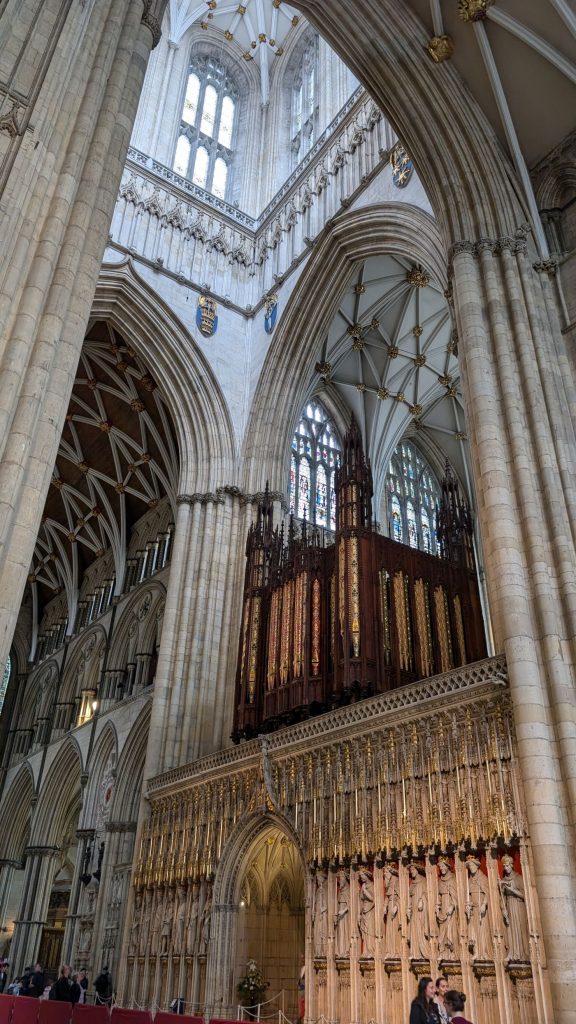

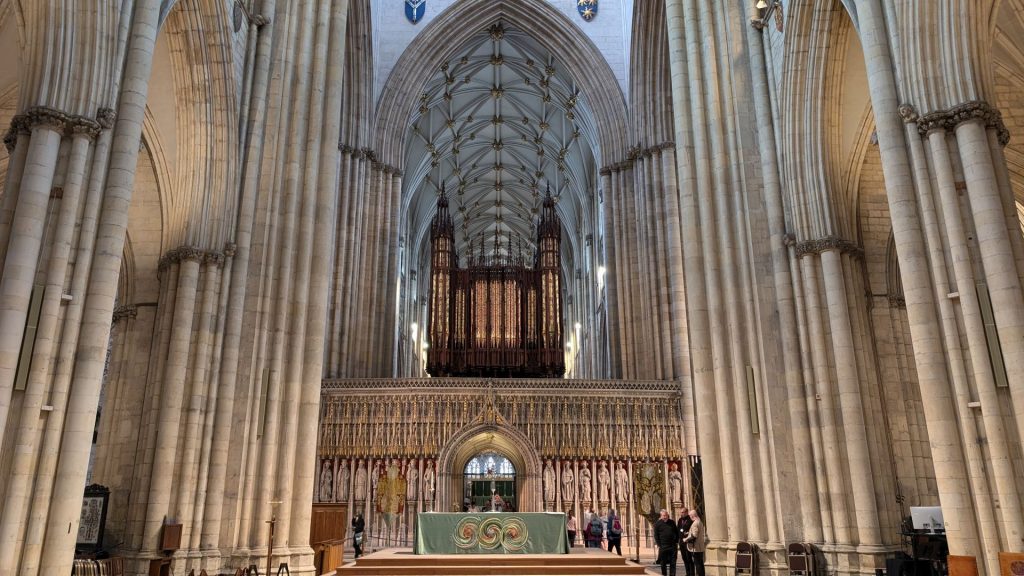

More interior pictures:

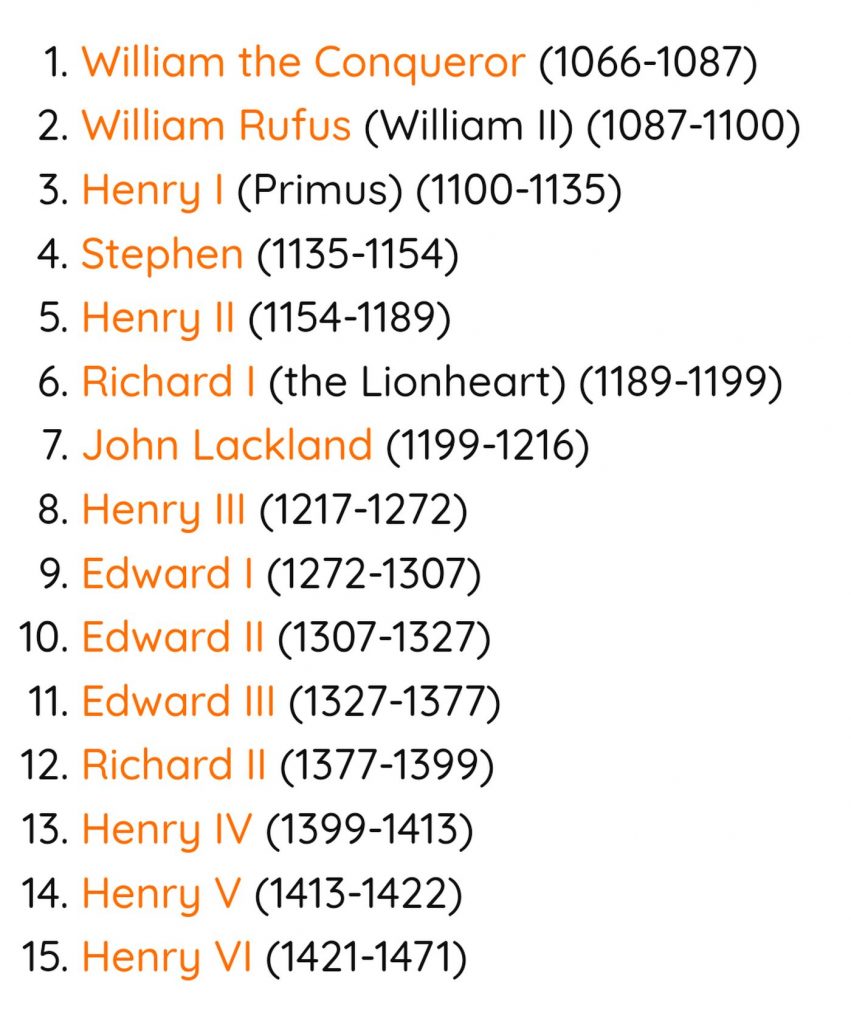

These 15 guys are on the York Minster Kings’ Screen, the choir screen separating the choir from the nave. It features kings ranging from William the Conqueror to Henry VI. Henry V originally commissioned the 15th century rood screen.

Here’s the list, for those few who care:

On another note, Archbishop William Thomson’s (archbishop from 1862 – 1890) marble effigy includes his dog, Scamp:

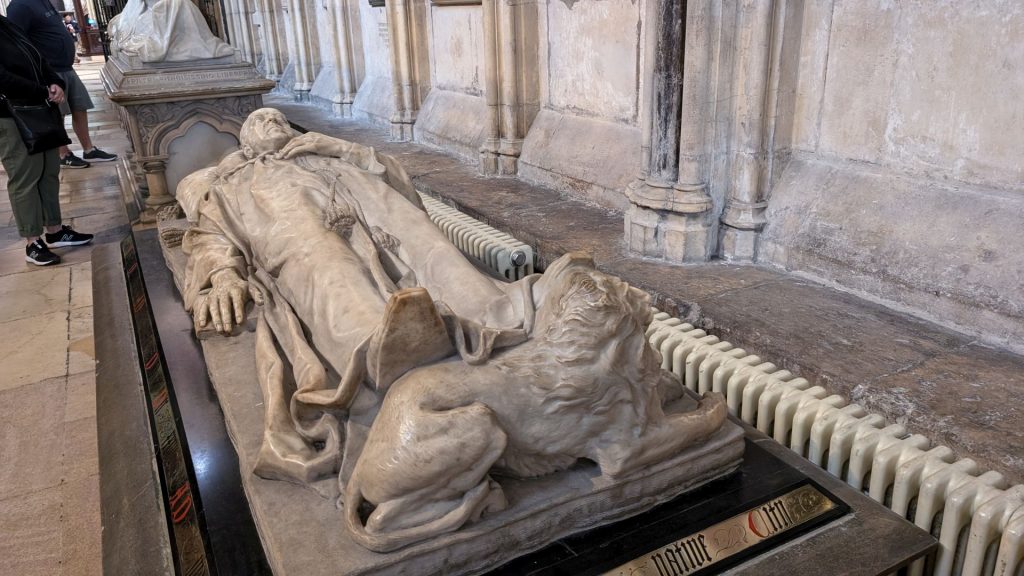

I neglected to note whose effigy includes a lion, but I thought it was interesting. A pet lion?

This astronomical clock is a memorial to the men of the Royal Air Forces working from bases in Yorkshire, Durham, and Northumberland, who were killed during the Second World War.

The clock shows an air navigator’s view of York, with the Minster in the center. The golden sun rises and sets on the horizon at the correct time throughout the year. It is surrounded by compass points, zodiac figures and a star map. The dials at the bottom show Greenwich Mean Time on the right and star time on the left.

The model below (close up on the right side) shows the elaborate construction of the roof of the octagonal Chapter House built circa 1285.

We are now going to the Western Crypt. It lies below the Quire and is an ancient space including the remains of the older section of the Minster. Here we see the famous Doomstone and the tomb of St. William of York, canonized in 1226 and the only saint buried in the cathedral. It also contains the font.

Pictured below on the left is the font. Its bottom is mid-15th century. It came from Bedern Chapel, York. The cover, designed by Sir Ninian Comper in 1947, commemorates the baptism of King Edwin by Bishop Paulinus in 627 in the first Saxon cathedral. The figures from left to right are: Queen Ethelbugha, King Edwin, Saint Paulinus, Saint Hilda (Abbess of Whitby), and James the Deacon.

Pictured below on the right is the Doomstone. The Doomstone survives from the first Norman Minster. It shows the “mouth of Hell” – a gruesome scene of lost souls slowly pushed into a boiling cauldron by devils and demons.

At the top left you can see a man carrying two bags of money, showing the sign of greed. To his right is a woman showing the sin of lust. The stone is also decorated with toads. Thought to be creatures of magic, they were associated with evil and darkness.

It is thought that this formed part of a much larger image on the west front of the 12th century Minster.

And now, a picture of the Tomb of Saint William, Patron Saint of York.

It was time to climb 275 steps up the tower to get a birds-eye view of York.

Exterior of York Minster:

We end our visit to York Minster with a few pictures of The Sovereign. The year 2022 marked the Platinum Jubilee of (then) Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II. She acceded to the throne on February 6, 1962 and was the first British Monarch to reign for 70 years. The creation of a new statue of Elizabeth II, and its installation on the West Front of York Minster in her Platinum Jubilee year, honors her life of service and dedication to the nation and the Commonwealth.

Our last visit of the day was to the JORVIK Viking Center. Scandinavian York or Viking York (Old Norse: Jórvík) is a term used by historians for what is now Yorkshire during the period of Scandinavian domination from late 9th century until it was annexed and integrated into England after the Norman Conquest; in particular, it is used to refer to York.

The JORVIK experience offers a fascinating glimpse into the cultural “melting pot” of 10th-century York. The city, a prosperous trading hub, welcomed goods and people from across the Viking world. Visitors can now encounter 22 new animatronic characters that vividly bring to life the diverse customs, traditions, and languages of York’s medieval inhabitants. Meticulous research has gone into faithfully recreating every aspect of these characters, from their clothing and facial features to the authentic sounds of Old English, Old Norse, and even Ancient Arabic – underscoring York’s role as a vibrant, multicultural center. This immersive experience allows guests to truly discover the rich tapestry of people who lived and worked in Viking-age York.

Here are just a few of the “people” we met on the ride.

As you enter Jorvik for the first time, you encounter Torgils the Hunter (pictured below). Hailing from Norway, Torgils greets you in Old Norse, welcoming you to Jorvik. Dressed in typical Viking fashion, he wears a woolen tunic over a linen shirt, embellished with tablet weave. His filed teeth and tattoos enhance his rugged Viking appearance.

Torgils carries a traditional English ‘D’ bow and the hare he caught for supper. His dog, about the size of a modern Alsatian, accompanies him, restrained by a chain and collar modeled on a 10th-century find from a boat grave in Uppsala, Sweden.

By the wharf, two fishermen (below) discuss their day in Old English, indicating they have lived in Jorvik all their lives. Karl laments his poor catch and needs to mend a broken net. Eymund sympathizes as he guts a fish. This fisherman is one of two reconstructions based on actual Viking-age skulls on the ride.

Samples from the mid-9th to early 10th century found at Coppergate (a street in the city center of York) show Jorvik’s impact on local fish stocks. Remains include eels, pike, perch, salmon, trout, smelt, and carp. By the end of the Viking period in York, two-thirds of the samples were herring. Few other marine fish reached the city as local river fishing increased, leading to more pollution.

Mord, Jorvik’s skilled leatherworker, diligently sews together the pieces of a shoe at his Coppergate stall. He is also selling his wares of shoes and scabbards. Unfortunately, Mord suffers from Dupuytren’s Contracture, a genetic condition also known as “Viking’s disease,” which hinders his work. This disorder, more common in middle-aged men, has caused his fingers to become clawed and impaired. Reportedly, the condition originated with the Vikings and spread across Northern Europe as they traveled and intermarried.

The leatherworkers of Jorvik produced a variety of footwear, including simple slip-on shoes as well as laced boots and shoes secured with leather straps or toggles. During the Coppergate excavation, archaeologists uncovered a highly unusual and remarkably well-preserved single-piece leather shoe. This distinctive design, featuring a central sole section with the sides folded up around the foot and then sewn together, has not been found elsewhere in Britain, suggesting it may have been brought by a foreign trader or slave.

At the end of Coppergate you can see an older inhabitant struggling to cross the road while using a crutch. Leoba is around 46 years old and is based on the analysis of one of two human skeletons found at Coppergate. She has a range of defects in her hips, legs, spine, ribs, shoulders, knees, hands and wrist. This creates a picture of a small middle-aged woman with a pronounced limp using a crutch due to a genetic problem with her right hip.

Leoba was found in a shallow pit close to the River Foss. She was possibly buried towards the edges of a group or in a cemetery outside the excavation area. She may have been an outcast since we found no other burials in the area.

Analysis tells us that she was robustly built standing at 5 ft 2 in but had a degenerative joint disease. Through isotopic analysis of the lead, strontium and oxygen levels in her bones and teeth we can tell where she grew up and her diet. Based on these findings we know that she was not originally from Jorvik. She likely spent her childhood by the coast, probably South-west Norway or the Northern tip of Scotland.

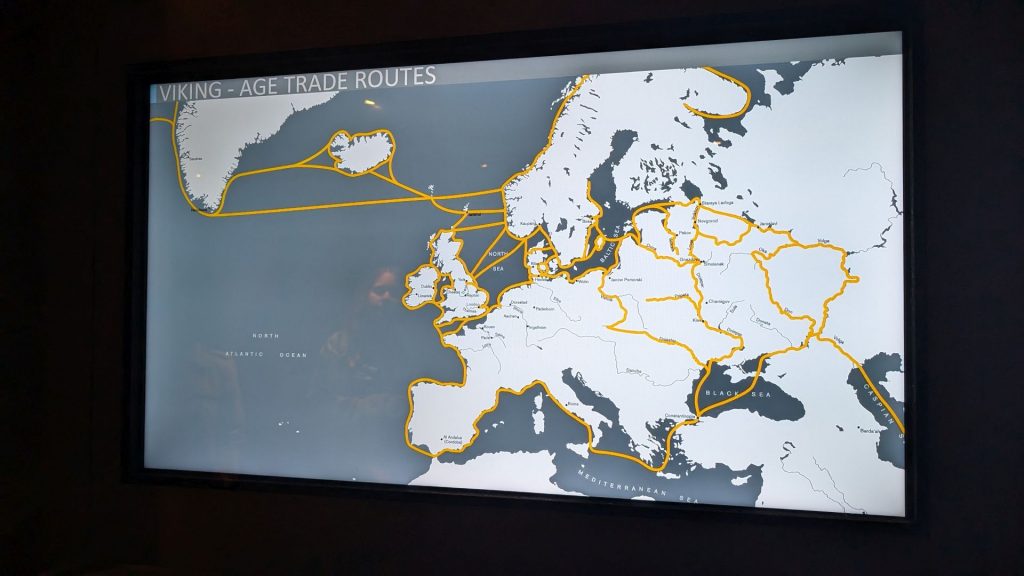

After the ride, we entered several rooms containing a LOT of relics from various locations. Jorvik was part of a vast intercontinental trading network. Local markets and regional supply chains provided foodstuffs and raw materials for building and manufacture. Check out the extensive trade routes:

Rich textiles, such as silks from Central Asia or the Easter Mediterranean, were highly valued luxury items and so may have been given as payments or gifts. At the other end of the social scale, the people of Jorvik made their own clothes from start to finish.

The Vikings showed their status through their clothing, jewelry, weapons and horse equipment. Dress accessories, like buckles, brooches and belt fittings, were made at Coppergate and worn by the people who lived there. Some of these objects reflect styles and decoration from places such as Ireland and Scandinavia.

Ordinary people walked everywhere so horse-riding equipment such as spurs, showed rank and authority.

“. . . for they were wont, after the fashion of their country, to comb their hair every day, to bathe every Saturday, to change their garments often, and set off their persons by many such frivolous devices.” John of Wallingford writing in the 13th century about the conduct of the Vikings in Britain.

Many bone and antler combs were found at Coppergate. They were made from several different parts and were time-consuming to make. These objects were valued possessions, as specially made protective antler cases have also been found.

Jorvik’s leather workers made many items including shoes, boots, belts, straps and sword and knife sheaths.

Ankle-shoes were popular. The one on the left below is for a left foot and has a double flap and toggle fastening. Slip-on shoes were also common. Shoes were made on a wooden last. The shoe on the right below still shows holes made by nailing it to the last. Most shoes from Jorvik are “turnshoes.” These were sewn together inside out and then turned the right way out.

The sock pictured below is the only Viking-age sock found in England and it is probably from Scandinavia. The sock is almost complete although worn, with holes at the toe and heel and signs of patching.

It is made of undyed wool with a red band at the top. The sock may have stopped at the ankle to form a shoe liner, or continued as a red stocking. (I don’t see the red band, but the sign said it was there.)

#8 below: Vessels containing fine wine were imported from the Rhineland, as was volcanic lava stone to make quern stones (stone tools for hand-grinding a wide variety of materials, especially for various types of grains).

#9 below: Silks were traded from Byzantium. The cowrie shell is from the Red Sea where it may have been used as payment. This coin, a dirham, says it is from Samarkand (Central Asia) but it is a fake made of copper, tinned to suggest silver.

People living in Coppergate had a reasonably healthy diet. There were seasonal variations and shortages, but meat, fish, cereals, vegetables, wild and cultivated fruits were all available. Intestinal worms caused by contaminated food or water were a common problem. Medicinal plants and herbs were used to purge the body.

#1 below: This (big!) piece of human feces contains eggs of whipworm and maw-worm, along with cereal bran. A small number of gut worms were not a problem for healthy individuals. Larger infestations in the young, sick and elderly could be serious.

#2 below: Cereals such as wheat and barley contain bran that remains undigested and survives well in the soil.

#3 below: Apples, sloes, plums, and cherries may have been preserved to eat out of season. They were sourer than modern fruit and used in sauces and wine making.

#4 below: Many hazelnut and walnut shells were found inside houses, probably because people tossed them on the floor.

#5 below: Sphagnum moss is very absorbent and was used as an early toilet paper. Some remains have traces of bran and worm eggs.

People used knives to prepare and eat food. There were no table forks.

These fine double-ended iron spoons have twisted stems and a fine coating of tin to make them appear silver. They are unusual finds. The bowls at each end differ in size and it is likely they were for measuring precious spices or medicines, rather than for eating.

Spiked iron holders for holding wax candles (below left) were driven into the walls for inside lighting.

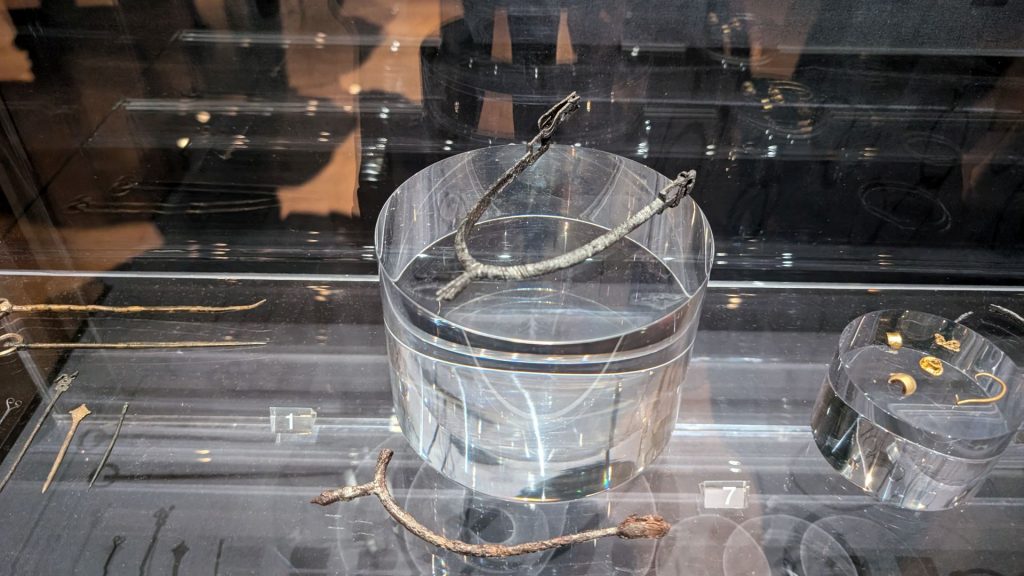

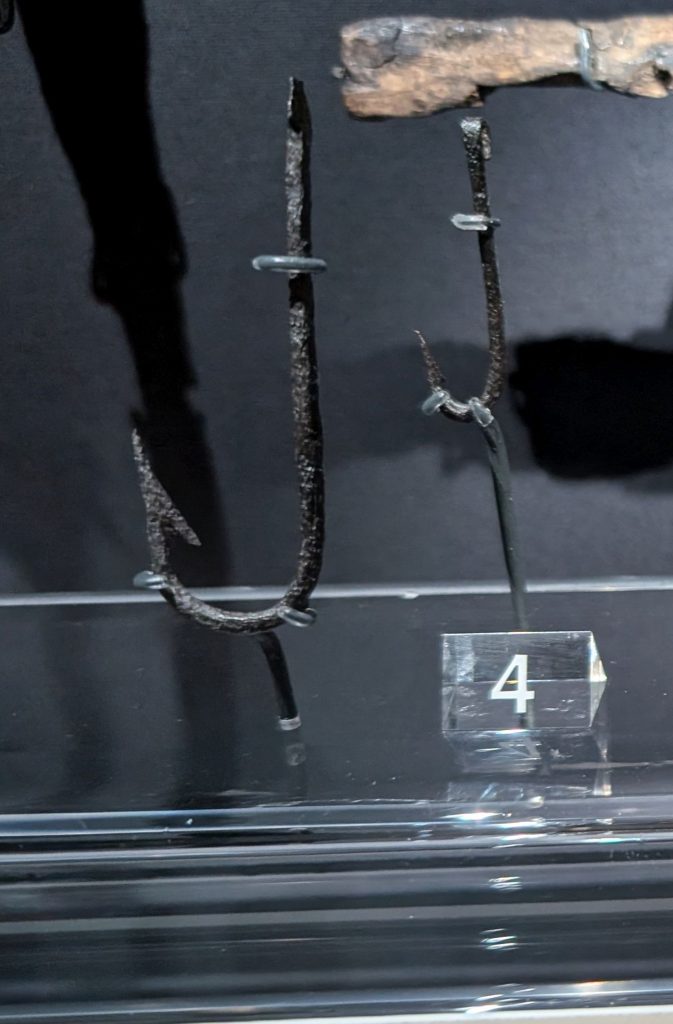

Fish were caught in local rivers using iron hooks (below right). Fish hooks are not common finds and only seven date from Viking-age Coppergate.

The Herefordshire Hoard was discovered by metal detectorists near Leominster in 2015. It consists of silver coins, gold jewelry and a single silver ingot. It was buried between AD 878 and AD 879 and is likely connected with the presence of the Viking “Great Army” in the Kingdom of Mercia during that period. The mixture of ingots and coins of different origin is typical of Viking hoards. The hoard is thought to have originally consisted of around 300 items, although only 33 have been recovered so far.

This gold and rock crystal pendant, possibly worn as an amulet, is the most unusual object in the hoard. While similar items have been found in Anglo-Saxon female graves in southern England, the decoration and materials used here suggest an origin in Frankia (modern France and western Germany).

The arm-ring is fastened by an animal-headed clasp. Arm-rings were important status symbols.

The gold ring is unusual for its very large size, octagonal shape and inlaid pattern. It is decorated in the Trewhiddle Style, suggesting an Anglo-Saxon origin. The black inlay is niello, a mixture of sulfur, silver, copper, and lead which was used to create a striking contrast with gold or silver.

The coin of Wulfred of Canterbury was the first to have a portrait of an archbishop instead of the kind. (Sorry, the picture is kind of blurry.)

The majority of coins in the hoard are Anglo-Saxon and date to the 870s. Most of these were minted for Kings Alfred the Great of Wessex (6) and Ceolwulf II of Mercia (7). Both successfully fought the Vikings for control of southern England in the 870s and issued coins with very similar designs, some of which were minted by the same moneyers (8). The seated figures on these “Two Emperor” style coins of Alfred (9) and Ceolwulf (10) also suggest an alliance between two rulers of equal status. Later accounts from Alfred’s reign instead minimize Ceolwulf’s importance. This “Portrait-Quatrefoil” type coin of Alfred (11) is exceptionally rare and is the only complete example of this type found to date.

This large pitcher made near Torksey, north of Lincoln, is one of the most stunning finds from Coppergate. The potter decorated it by pressing his thumbs into the wet clay.

If you’re still hanging in with me (this is a lot of info!), good for you! If not . . . . well, you aren’t reading this. 🙂 I want to share a bit more, though . . .

Metalworking

Viking-age smiths were masters of their craft. Those making weapons held the highest status, followed by smiths who made high-quality edged tools. The Coppergate smiths worked with hammers, tongs and bellows, making everything from knives, needles and nails to intricately crafted padlocks. Padlocks were used to secure doors, chests and boxes. They were either box-shaped or barrel-shaped. The barrel padlock pictured below has an internal spring operated by inserting a key at one end.

Iron, copper, lead, tin, pewter, silver and gold were all worked at Coppergate. This required a high level of expertise and cooperation between craftspeople. They used a sophisticated network of supply for raw materials.

Iron ore was smelted to produce iron alloy bars outside the city. These bars were transported to Jorvik, perhaps by boat, and then traded within the city. In this period all iron artifacts were forged (heated and hammered) in a hearth. Lead, tin or bronze was cast (melted and poured into a mold).

Blacksmiths often used different iron alloys, including steel, within one object. This shows that they knew that alloys had different qualities, such as hardness and brittleness. These alloys could have come from different places or be produced by one person.

Woodworking

Due to the waterlogged oxygen-free soils at Coppergate may wooden objects survived that would usually have rotted away after 1,000 years.

Bowls and cups were made on a pole lathe, mostly for food preparation or eating and drinking. Some of the bowls were highly valued as they were repaired when broken or split. Three cups show traces of painted decoration. Coppergate is thought to mean “the street of the cup-makers.”

Many woodworking tools were found. An iron shave may have been used by a cooper to smooth and shape wooden pieces of a barrel or bucket. The wall of the box pictured below is formed from a thin narrow strip of wood called a lath. The lath was bent into a circle and the two ends sewn together with organic thread. The ash-wood wall is decorated with different designs and is attached to an oak base with wooden pegs. A similar one was found in Hedeby, a Viking trading center.

Saws were used by both wood and antler workers. This decorated antler handle from a bow saw is a very rare find. The blade fitted into a cleft at the tip and was attached to a peg in the slot at the other end.

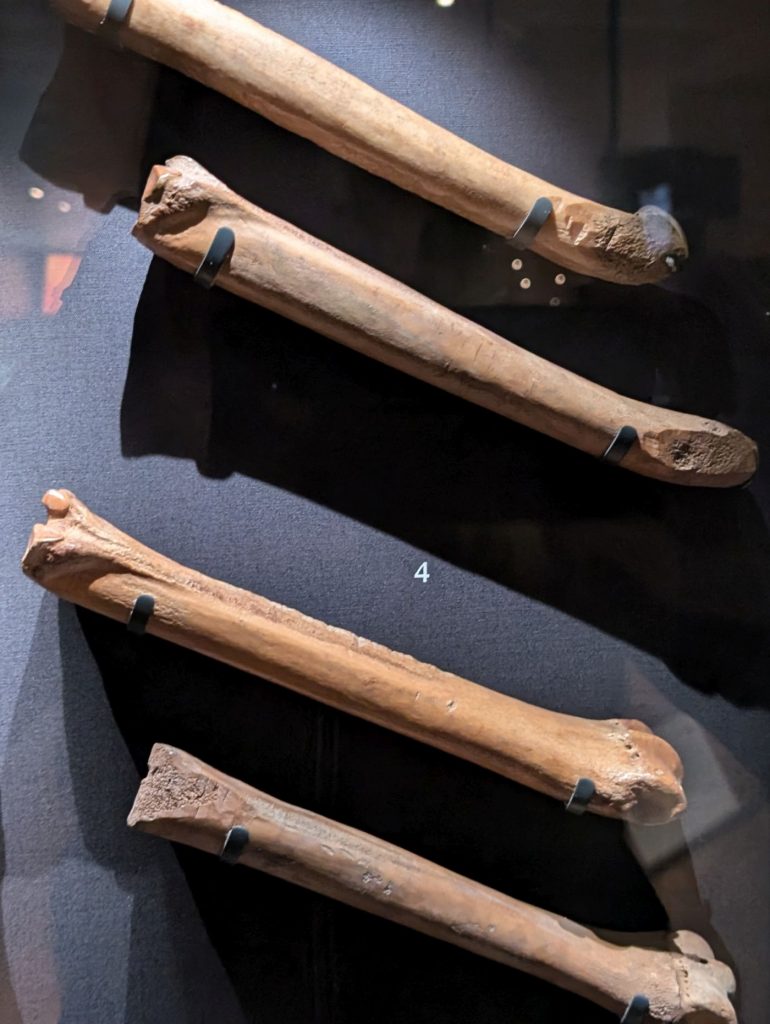

In case you are wondering whether they had fun, they apparently did! For example, bone skates were strapped to feet with leather thongs so they could ice skate. Poles with iron tips were used to pull the wearer across the ice. Bone skates (they look so comfy – NOT):

And they made music!

Music was played and sung in church, at festivities and in households. It was created on wing, string, and rhythm instruments. The 10th century Arab trader, al-Tartushi, likened Viking singing to the sound of howling dogs. Nice. 🙂

#1 below: This is perhaps a key for tightening tuning pegs on a lyre. It features two birds being swallowed by two dragons. Three-dimensional depictions like this are unusual in Viking-age art.

#2 below: Lyres were the main instrument of professional poets in the Viking Age. This bridge is probably for a round lyre with six strings.

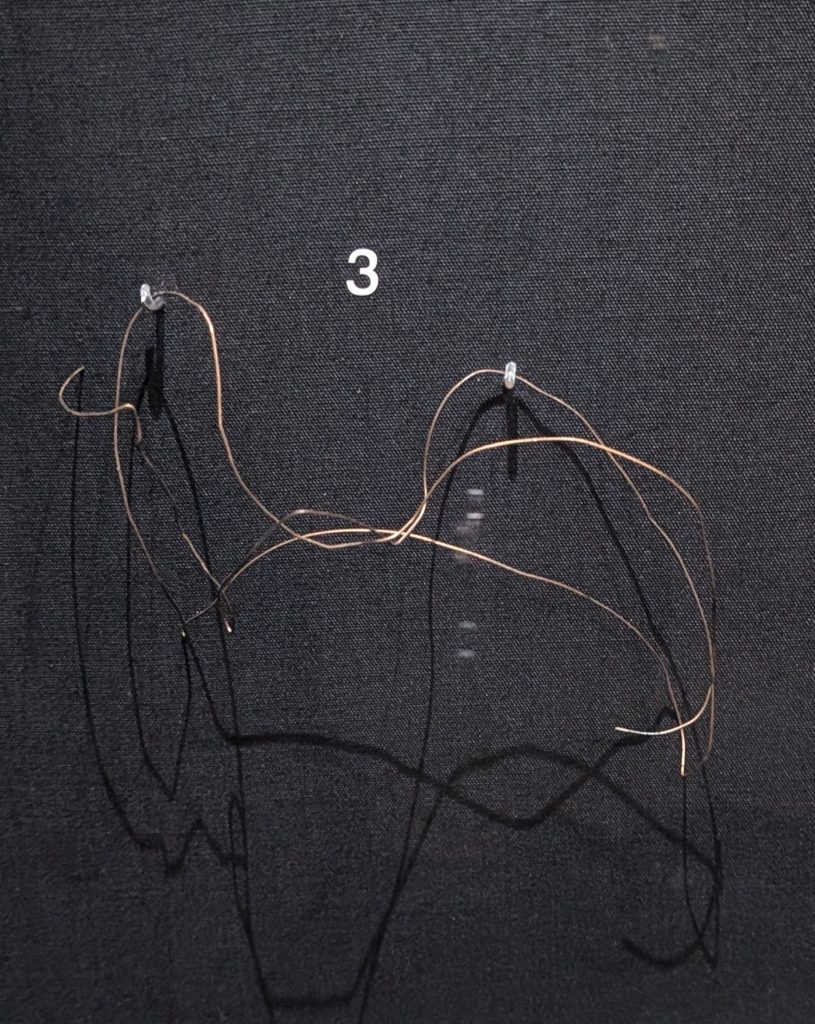

#3 below: A length of copper wire which could be used for stringing an instrument.

#4 below: These panpipes are made of boxwood – a rare and expensive material. Five out of seven notes survive. Tubes made from bird bones may also be panpipes. Bird bones are ideal for such instruments because they are hollow.

#5 below: The larger of these two flutes is made from a goose or mute swan’s wing bone. Not all the finger holes have been completed and the fipple (mouth piece) of wood or beeswax is missing.

#6 below: Many drilled pig trotter bones were found at Coppergate. They could be buzz bones. Threaded on a twisted cord, they spin and hum when the cord is pulled taut.

Even the most tenacious history buffs are likely tired of reading this post by now. I want to know that I am giving you a standing ovation for making it all of the way through. I hope that helps.

I am going to end this post by plugging a TV series (available on Netflix) that loosely relates to this post: The Last Kingdom. It is a British historical drama television series created and developed for television by Stephen Butchard, based on The Saxon Stories series of novels by Bernard Cornwell. Check it out! I predict that about 90 percent of the ladies and about 10 percent of the gentlemen viewers will fall in love with Uhtred. I know I did.