We were scheduled to return the rental car by noon in Glasgow. It didn’t happen.

Minutes before we planned to leave Oban, the guest house’s proprietor knocked on our door and informed us that there had been a hit and run in Oban at 2:00 a.m. This caused the road (as she described it, the only road to Glasgow) to be closed. She said the police in Glasgow had been notified (there are either no local police in Oban or those that are there are not equipped to handle hit and runs), but they weren’t expected to arrive until later that afternoon. In short, she told us that we would probably be in Oban for most of the day.

Despite this warning, we decided to take our luggage to the car. We hoped to flag down someone who might be able to tell us of another way to Glasgow. As luck would have it, a nice woman was on her way to work and pulled over when we waved at her. She did, in fact, know of another route out of town to Glasgow that was longer, but not “too much” longer. She also told us that it was a pretty drive.

So we took it. The drive was, indeed, pretty.

We finally returned the car (well after noon, but without penalty), took a bus to the hotel and stopped for lunch. Two of the things we wanted to see closed soon after we arrived at the hotel so we decided to use the rest of the afternoon to plan the next day’s visit in Glasgow.

The next day’s visit in Glasgow

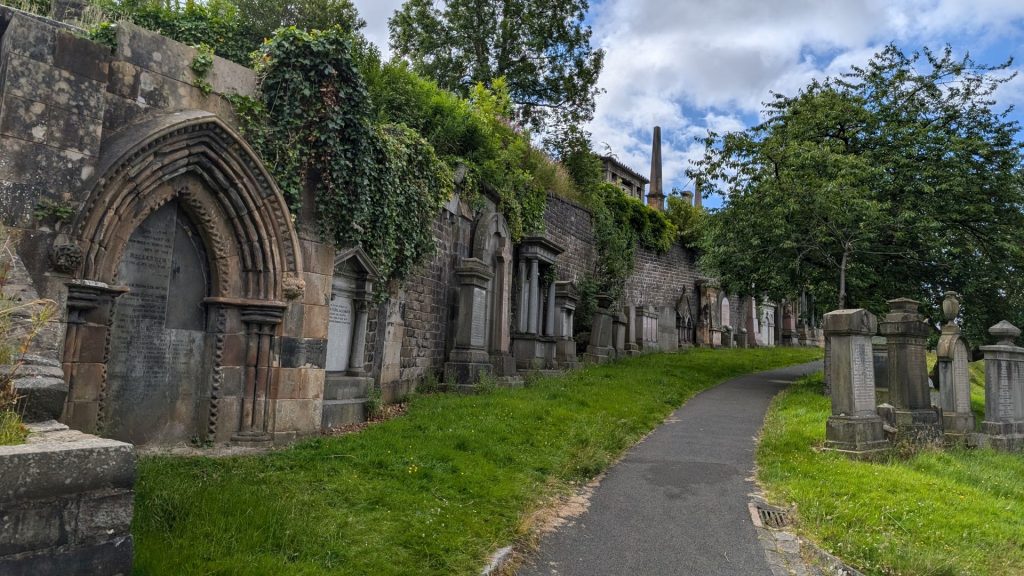

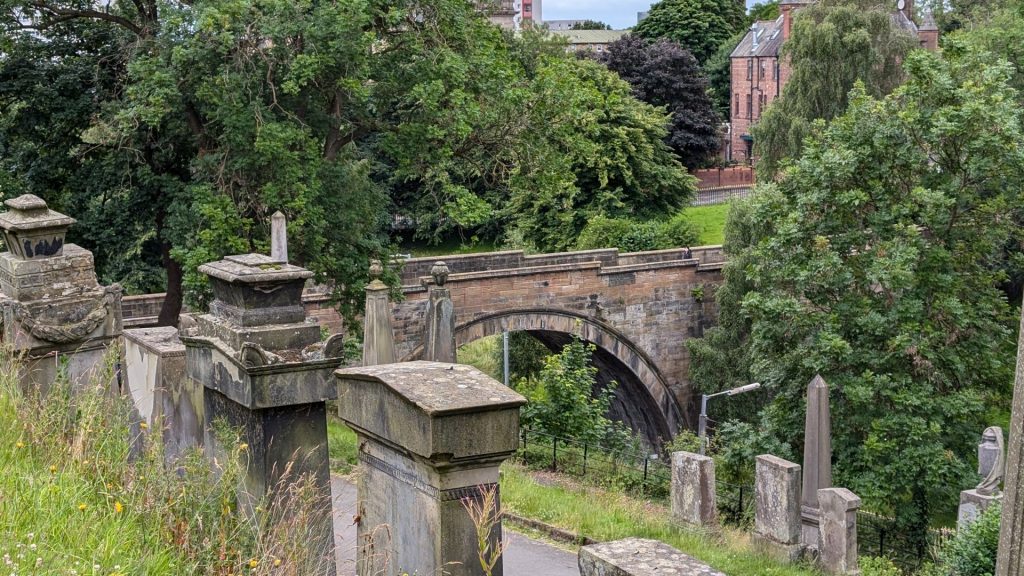

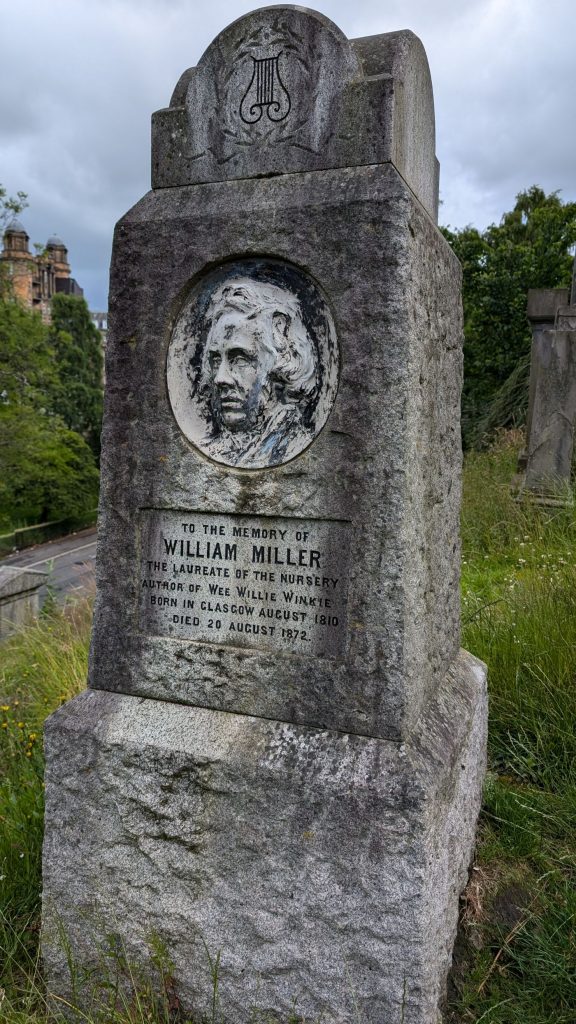

My day (Michael skipped the first stop) started with a visit to the Glasgow Necropolis. Early in the 19th Century a cemetery was built in the East of the City, adjacent to Glasgow Cathedral and the Royal Infirmary. The Glasgow Necropolis was built on a low, but very prominent hill and fifty thousand individuals are buried there. It was modeled on the Pere laChaise cemetery in Paris. This Victorian Garden Cemetery has 3,500 monuments. Many of the merchants who made Glasgow the “Second City of the British Empire” are buried there.

Here are several pictures from the walk to and of the necropolis.

I’d read that there are eye-catching murals throughout the city. These works of art were commissioned to brighten up the city’s streets. I made an effort to find quite a few of them.

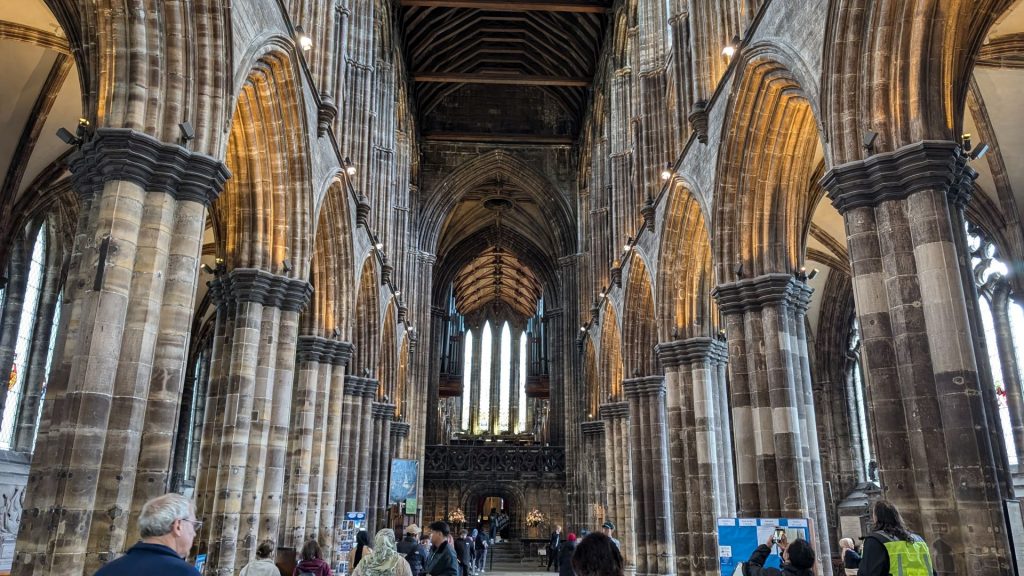

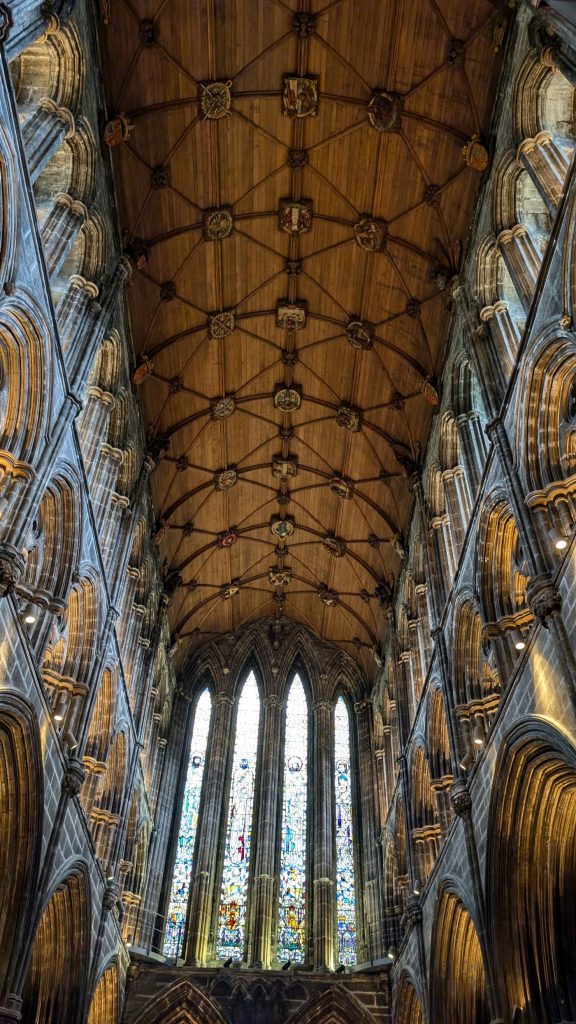

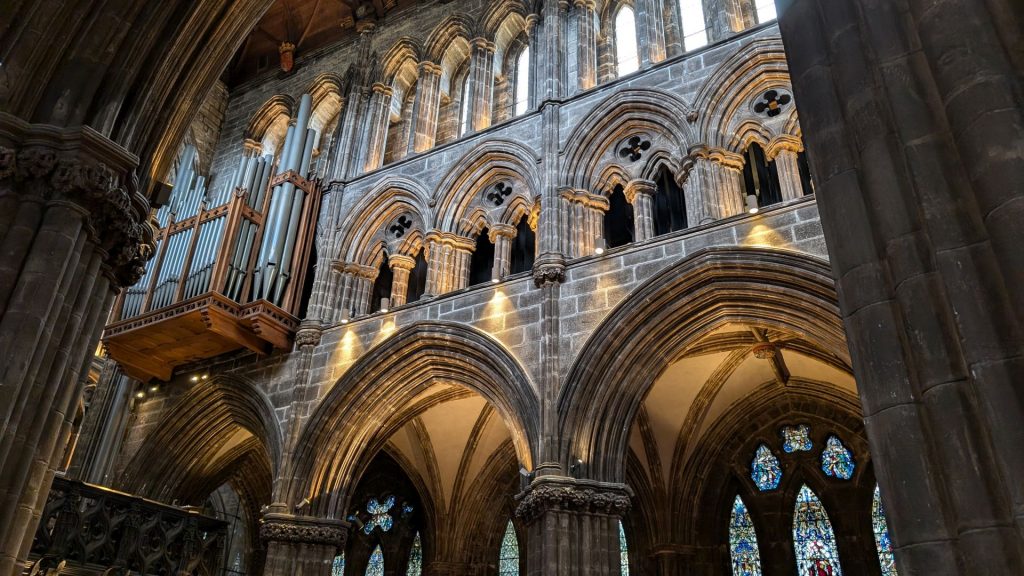

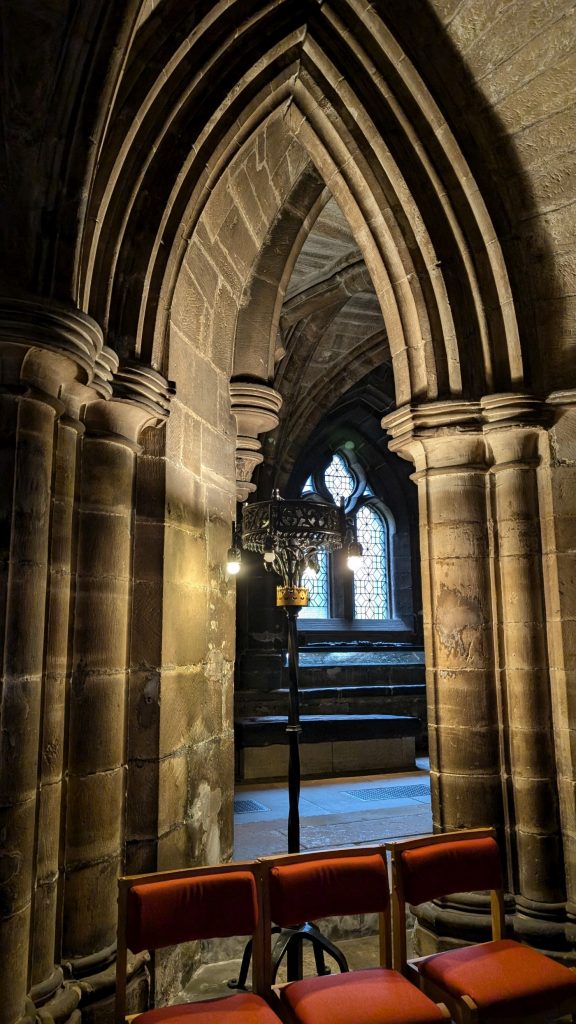

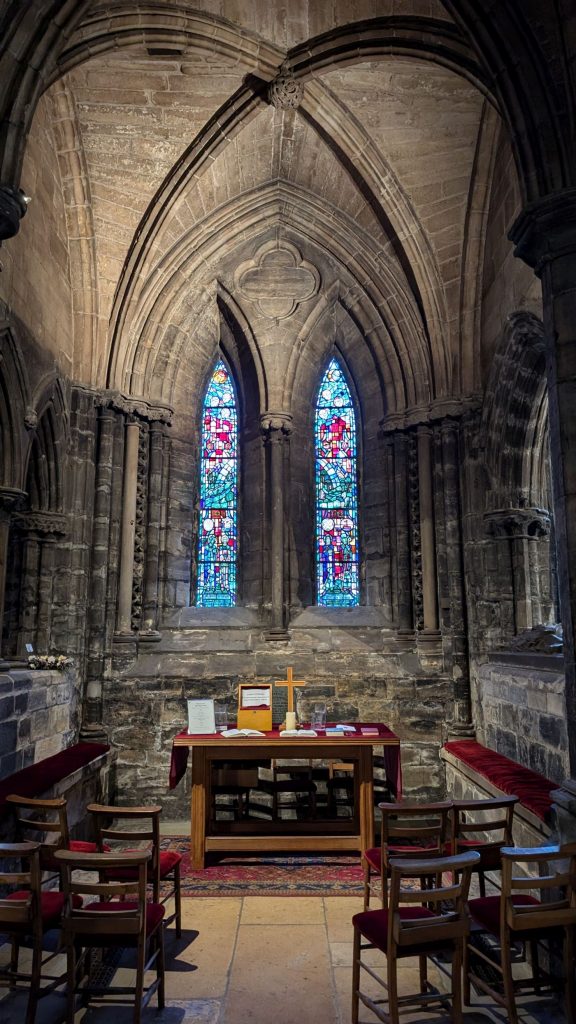

We visited Glasgow Cathedral next. You saw a picture of the exterior above, but now we went inside. The Cathedral is Glasgow’s oldest building. Consecrated in 1197, it was declared to be equivalent to Rome as a place of pilgrimage by Pope Nicholas V. The Cathedral was the point around which the town of Glasgow was originally built.

The cathedral was originally a Catholic place of worship. However, following the Protestant Reformation of 1560 it became a Protestant Kirk, which it remains today as part of the Church of Scotland. It is the only medieval cathedral on the Scottish mainland to have survived the Reformation virtually intact.

Pilgrim Central

The cathedral was built as a fitting setting for the shrine and tomb of St Mungo. Pilgrims queued here, in the nave, following a set route around the cathedral to St Mungo’s shrine and tomb.

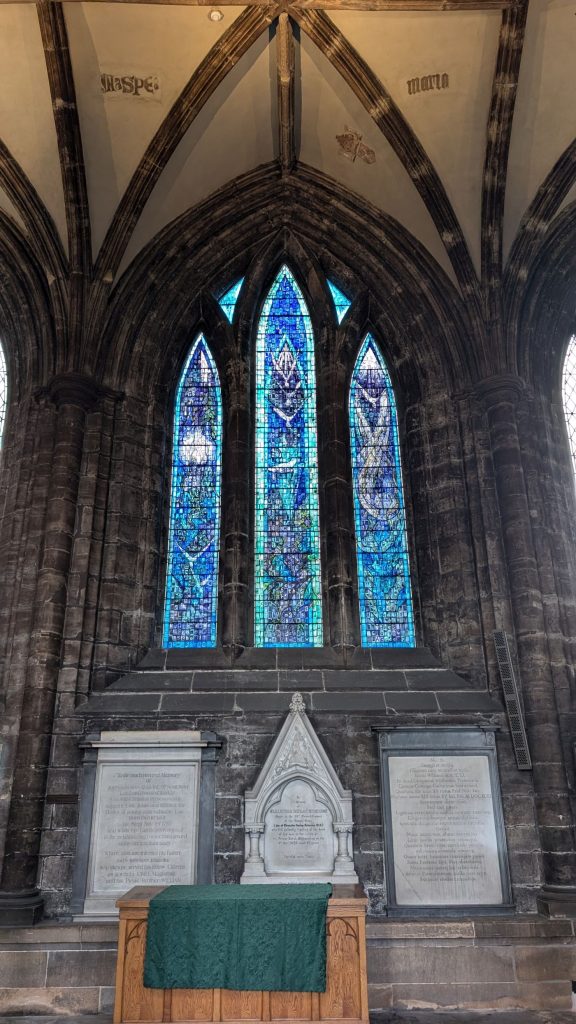

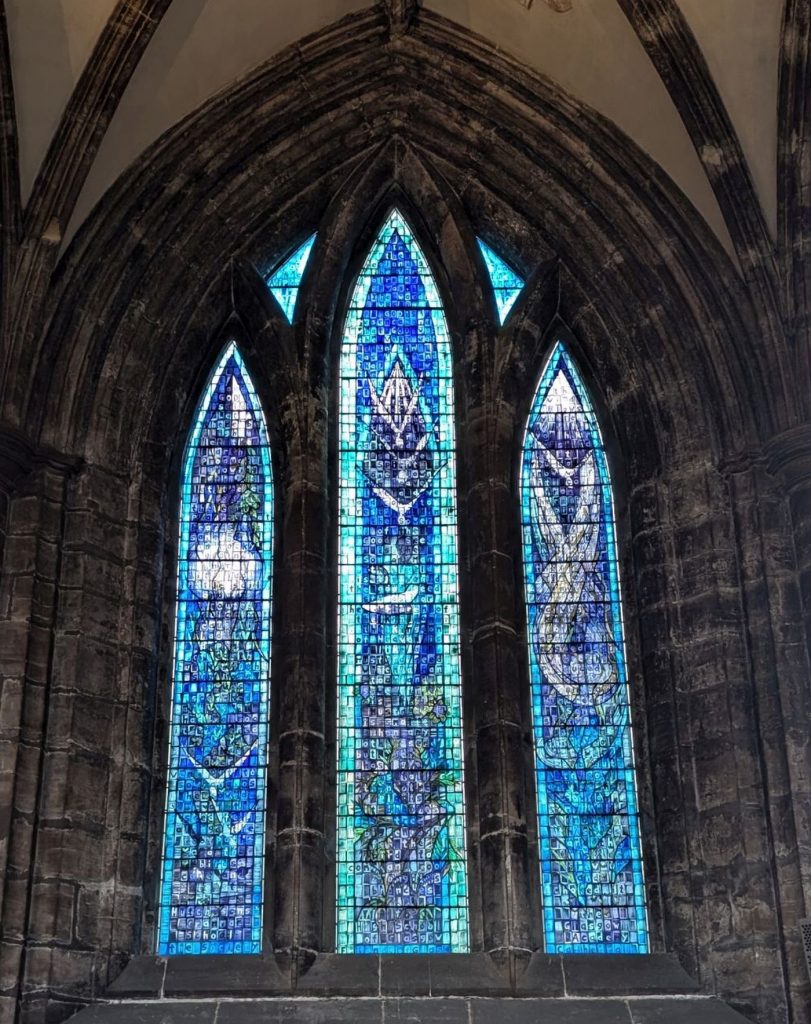

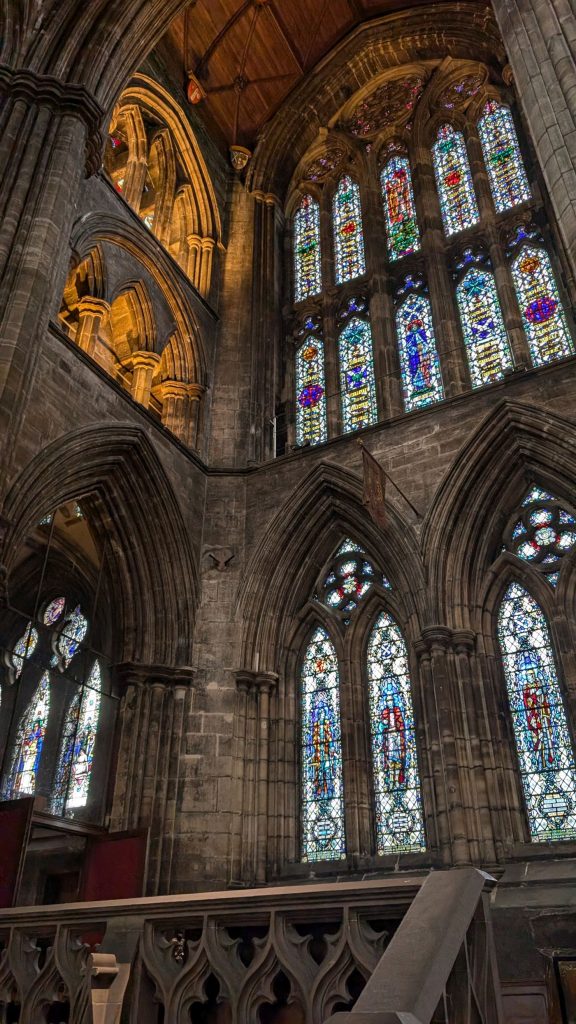

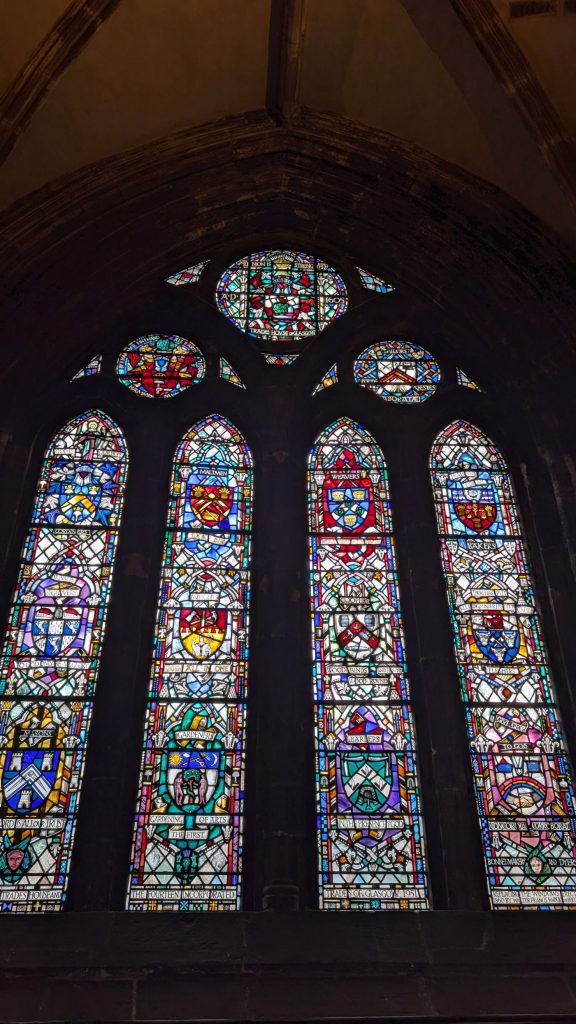

The Cathedral’s windows

The cathedral is blessed with a fine collection of stained glass windows, that ranges from 12 small panels of 16th century Flemish roundels to contemporary work. However, it is the outstanding collection of post-war glass that makes Glasgow cathedral special.

Most of the cathedral’s medieval glass was replaced in the 1850s and 1860s with stained glass made in Munich by the Royal Bavarian Stained Glass Establishment. The glass didn’t last long, suffering from the effects of pollution which caused the painted surface to deteriorate. Some were removed during the 1930s and today only two Munich glass windows remain in their original setting.

The glass now represents the largest single collection of Munich glass in the world. The Bavarian Glass factory was destroyed during the Second World War, along with many examples of its work in Germany.

One particularly stunning window is the Millennium window (1999), which is in the north wall of the nave. It was designed by John K Clark and made by Derix Glasstudios. The Millennium window was technically an exceptionally difficult window to make, but one that successfully weaves together text and symbolism to make a powerful statement.

Also famous is The Great West window on the theme of The Creation (1958), by Francis Spear. I believe the two figures are Adam and Eve, based on the theme. (I didn’t do a good job of getting a straight shot. Trust me, it isn’t tilted in real life.)

And then we have The Great East Window, The Four Evangelists by Francis Spear, 1951. Who are they? Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, of course!

Here are several pictures of other beautiful features of the cathedral.

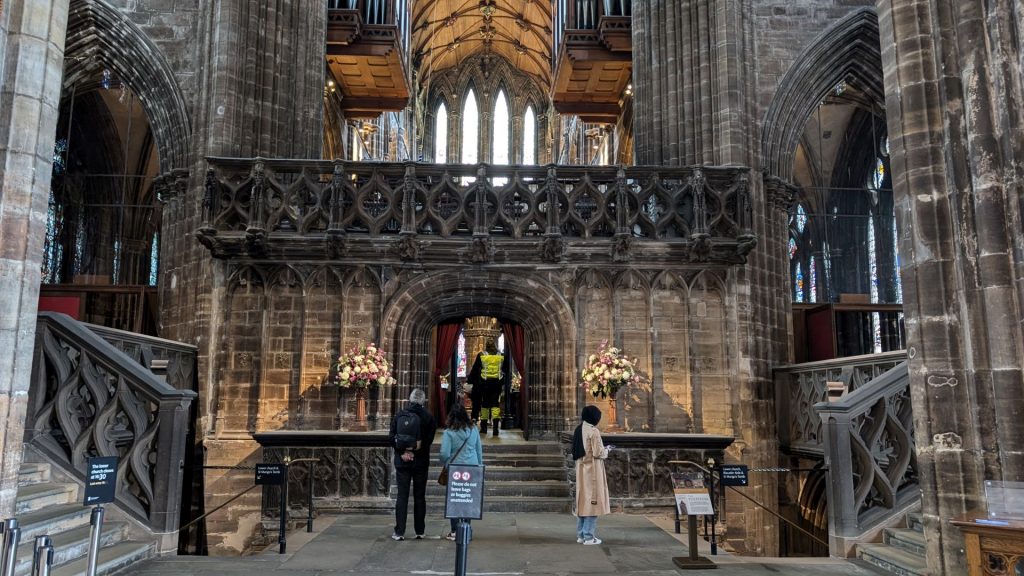

Pictured below is a “pulpitum.” This screen was added in the 1400s. The ornate stone screen divided the church – the public worshiped on this side, while nobles and the clergy held services in the choir beyond. At the top is a series of carvings. They may represent the seven ages of man or possibly the seven deadly sins.

Altars stood on the platforms on either side of the stairs at which worshippers would offer prayers. Eleven carved figures adorn the altar platforms. They might be saints. Popular belief suggests that they could represent Jesus’s faithful disciples.

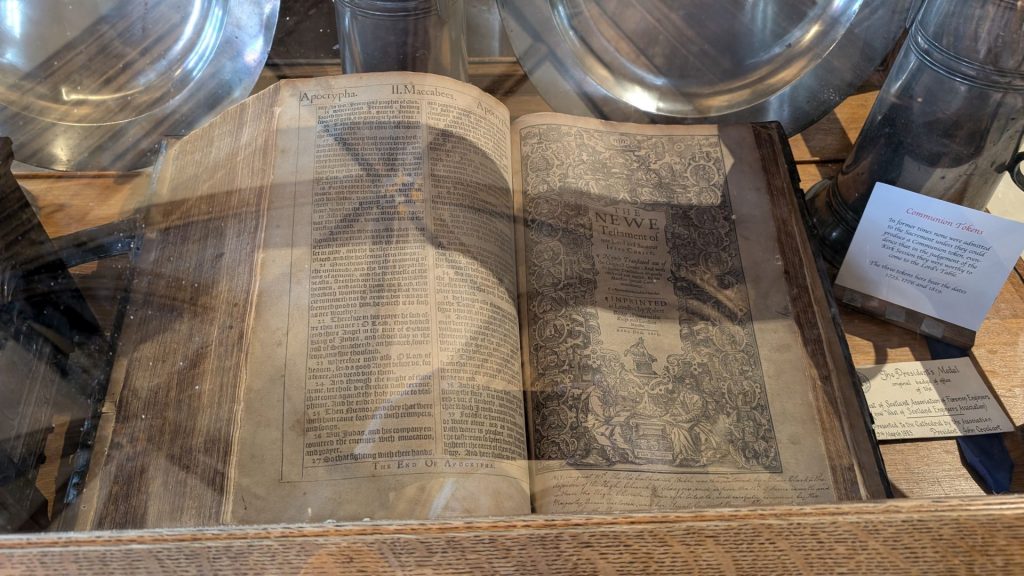

The book pictured below is The Reader’s Bible. This early printed copy of the King James VI Bible (first printed in 1611) was printed in 1617. It has wooden covers and a chain with which it was secured to a lectern.

The Reader would read to the congregation (most of whom were illiterate) for up to an hour before the minister began his sermon. (An hour seems like a long time to me, but if these people couldn’t read it on their own, it makes a lot more sense.)

It disappeared from the cathedral about 250 years ago and was found again after about 100 years in someone’s attic (!!). It was returned to the cathedral and was on display when Queen Victoria and Prince Albert visited in 1849.

Pictured below is The Law Monument. The 17th century monument of Archbishop James Law (1615-1632) is in the Chapel of St. Stephen and St. Lawrence. Archbishop Law was an Archbishop of Glasgow and was a generous benefactor to schools and hospitals in Glasgow.

Just when you think you’ve seen the entire cathedral (well, that was true for me anyway), you realize that there is also a Lower Church. What?

The Lower Church was built in the 1200s as a fitting setting for the tomb of St Mungo. The tomb was the culmination of the medieval pilgrim’s route and the most important part of the cathedral.

The Lower Church was also an ingenious solution to counteract the slope the cathedral is built on. Lying directly below the east end of the cathedral, the complex array of vaults and columns were built to help support the weight of the choir above.

Let’s learn a bit more about St Mungo, since we’ve read his name several times in this post.

Saint Mungo is the Patron Saint of Glasgow and also known as Kentigern who is believed to have been born and brought up in Culross in Fife. Mungo is believed to have begun his Christian Ministry at aged 25 around the year 540. Mungo established himself in Glasgow living a simple life beside a tributary known as the Molendinar and Mungo set up his Church which is the site of Glasgow Cathedral.

Legend of St Mungo

The Glasgow coat of arms relate to the life and legend of St Mungo. The arms include “the tree that never grew” relating to St Mungo tending a fire in St Serf’s monastery but he fell asleep and some lads who were envious of Mungo’s favored position with St Serf put out the fire while he slept. When Mungo woke he broke off branches from a frozen hazel tree and by praying over them and lit the fire again. The hazel branches were transformed into a fully grown tree. The “bird that never flew” is about a robin that had been tamed by St Serf and it had been accidently killed. Mungo prayed over the robin and brought it back to life. The “fish that never swam'” is about a ring which a King gave to his wife Langeoreth, who gave it to her lover, a knight who wore it. When the King noticed this, he took it from the knight when he was sleeping and threw it in the River Clyde. The King then demanded to see the ring from Langeoreth. She confessed this to Mungo who sent a monk to fish the river and found the lost ring. The bell is attributed to a bell that was reputedly given to Mungo by the Pope.

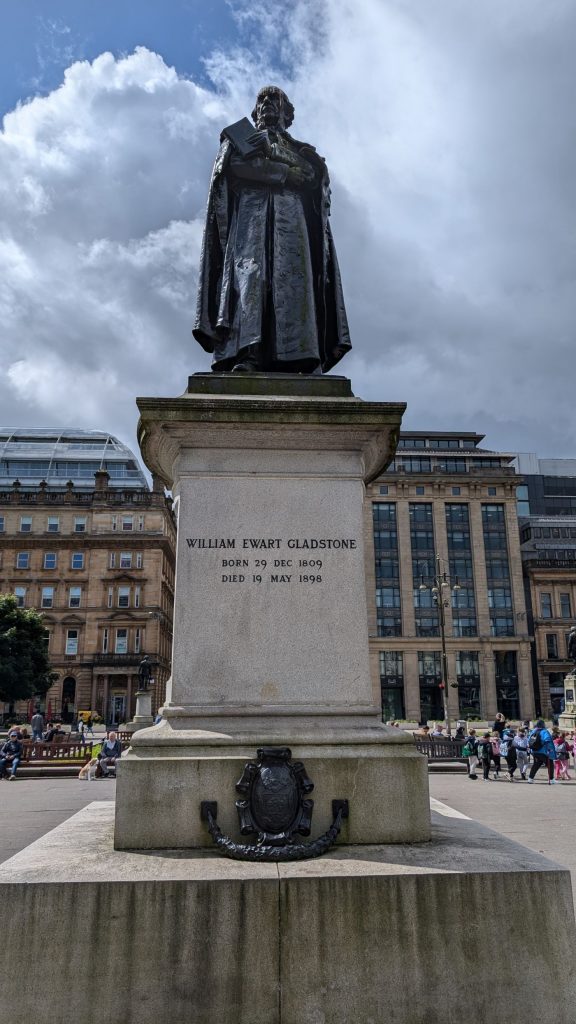

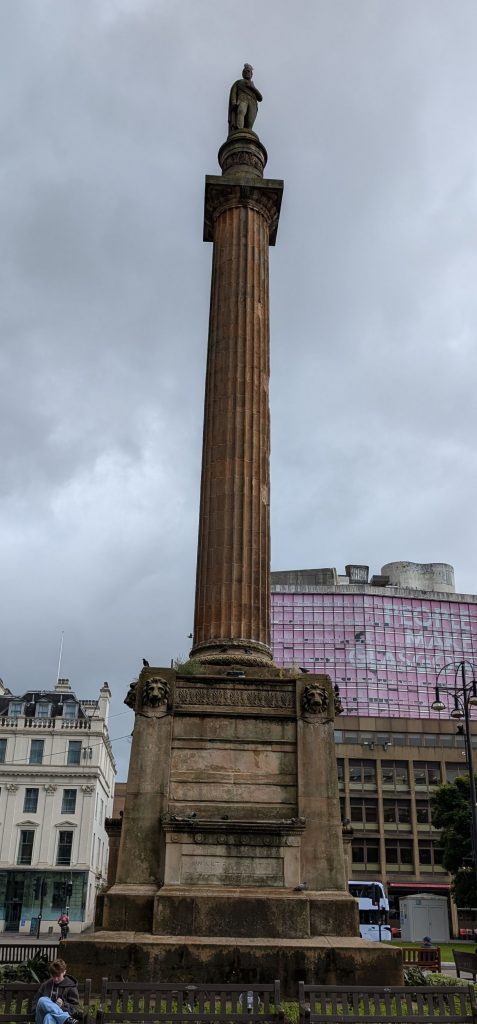

We had one last major stop to make before catching the flight to Belfast: George Square, considered to be the heart of Glasgow. We enjoyed the magnificent architecture of the buildings surrounding the square, as well as the numerous statues, many of which had birds atop them (or evidence of birds having been atop them, if you get my drift).

The cenotaph pictured below (first two side-by-side pictures) and the surrounding area are dedicated to the memory of those who gave their lives for their country. People are asked to respect it and refrain from using it as seating or a play area for children.

The statues were of some pretty amazing people.

Four times Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone (below left) was born in Liverpool and began his parliamentary career in 1832. The unveiling of the statue took place in October 1902 with the ceremony being performed by the Earl of Rosebery. The statue was moved to its current location in 1923 during the construction of the Cenotaph.

Former Prime Minister Sir Robert Peel (below right) entered parliament as a Tory in 1809. As Home Secretary from 1822, he was instrumental in the reform of the criminal law and in 1829 he introduced into London the improved Police which he had established in Ireland. The decision to erect a monument to Sir Robert Peel in Glasgow was made at a public meeting in the Trades Hall. The statue was erected in June 1859.

Thomas Campbell (below left) was a Scottish poet, historian and political commentator, born in Glasgow. His successful literary career began with the Pleasures of Hope, published in 1799, and other poems he composed include The Exile Of Erin, Ye Mariners of England and Soldier’s Dream. In 1826 he was elected Lord Rectorship of Glasgow University, in competition against Sir Walter Scott. Campbell is buried in the Poet’s Corner of Westminster Abbey.

Sir John Moore (below right) was a British army officer brought up in the Trongate, Glasgow. He began his military career at 15 and served as captain-lieutenant in the Duke of Hamilton’s regiment in America. He rose through the military ranks and earned a reputation as one of the greatest trainers of infantrymen in military history. The effectiveness of his method was shown in the Peninsular War, where he was sent in 1808 to combat Napoleon. He defeated the French army at the Battle of Corunna in 1809, but was killed by a cannon shot.

James Watt (below left) was a Scottish inventor and mechanical engineer, born in Greenock. He designed the first economical steam engine in 1769 and patented an improved version which had a separate condenser to reduce the consumption of fuel and steam. He came up with the idea of the condenser while walking on Glasgow Green one Sunday in 1765. The unit of electrical power was named in his honor in 1882. Watt and his sculptor Chantrey were close friends and this statue, one of several in Glasgow, was said to be a great likeness to Watt.

Field Marshal Lord Clyde, (below right), educated at the High School of Glasgow, was a British Army officer who famously commanded the Thin Red Line of the 93rd Highlanders during the Crimean War, driving back the Russians at the Battle of Balaclava. He later became Commander-in Chief of the Indian Army and was nicknamed Old Careful because of his concern for the men under his command.

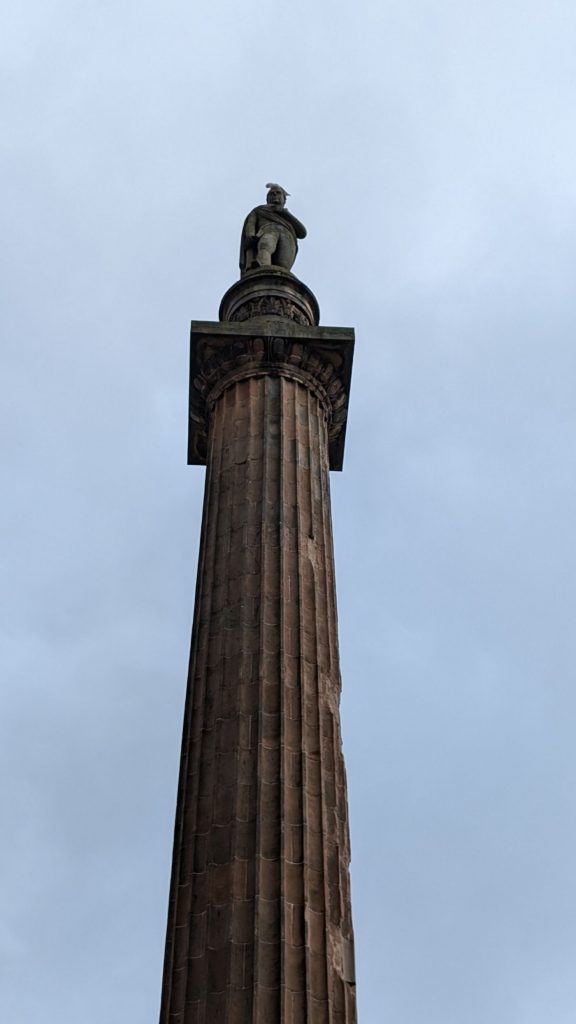

Sir Walter Scott (four pictures below – the bird chose the best viewpoint) was an internationally acclaimed novelist and poet of works including Rob Roy and the Lady of the Lake. He was the first English-language author to have many contemporary readers in Europe, Australia and North America. Glasgow’s was the first public monument to Sir Walter Scott anywhere in the world, 10 years ahead of the completion of Edinburgh’s Scott Monument on Princes Street. This was by far the tallest statue in the square.

Queen Victoria (below left) succeeded to the throne in 1837 and first visited Glasgow in August 1849. Her great love of Scotland prompted the acquisition of Balmoral Castle as a royal residence, which she had rebuilt in 1856 and visited almost every year until her death. The monument shows the Queen seated side-saddle, holding an imperial scepter raised in her right hand.

Prince Albert (below right) married Queen Victoria in 1840 and together they purchased the Balmoral estate in 1852. The statue was erected five years after his death. At the time, it was felt that an industrial city like Glasgow should commemorate a Prince who had been influential in social welfare and the advancement of industry. There was huge debate on what form the statue should take, but the Queen expressed a strong preference for the depiction of Albert on horseback, and she also suggested Marochetti be commissioned.

We passed by one more site before heading for a pint. This is the Gallery of Modern Art in Royal Exchange Square. It’s easy to spot because outside sits the famous Duke of Wellington Statue, which has featured a traffic cone on its head since the 1980s! Many people mistakenly believe that the Duke’s statue is an art installation and is connected to the Gallery. In fact, the statue is not connected to the gallery in any way. The cone was originally placed there by mischievous students. It was immediately removed by the police. However, the students returned at night to replace it and a long-running battle ensued! Eventually, it was decided that the cone should stay in place – a victory for the students who had created what is now an iconic landmark! Sometimes, also the horse of the Duke has a traffic cone on his head. The Gallery itself was originally the 18th-century mansion of William Cunningham, a tobacco magnate. With its stained-glass windows and Corinthian columns, the building is quite beautiful.

Sights on our way to get a pint:

That’s it for Scotland. We started our trip to the Island of Ireland the next day. Stay tuned!