As you learned in our last post, we’d just finished a puzzle. But we didn’t have any more on Seahike!

Tragedy! What to do? Google “toy stores near me,” of course! And who’d thunk, there is a Toys (backwards R) Us within walking distance (4.8 km). Google Maps took me on a rather strange route. I quickly ended up on a dusty dirt road. . . with a chain link fence blocking the path.

But wait! Some determined soul had cut a hole in the fence just big enough to get through if you crouched down and weren’t super-sized. My first thought was that I should turn around and go another way. But then I told myself, “Cindy, someone took the time to vandalize this fence and it would not be fair to them if you didn’t take advantage of their handiwork.” So I did.

Here are a few pictures of the route.

After the dirt road, then the dirt path ended, I walked along a street with no sidewalk for a time until I reached a small shopping mall. Behold: Toys (backwards R) Us and Spanish puzzle heaven! I bought two.

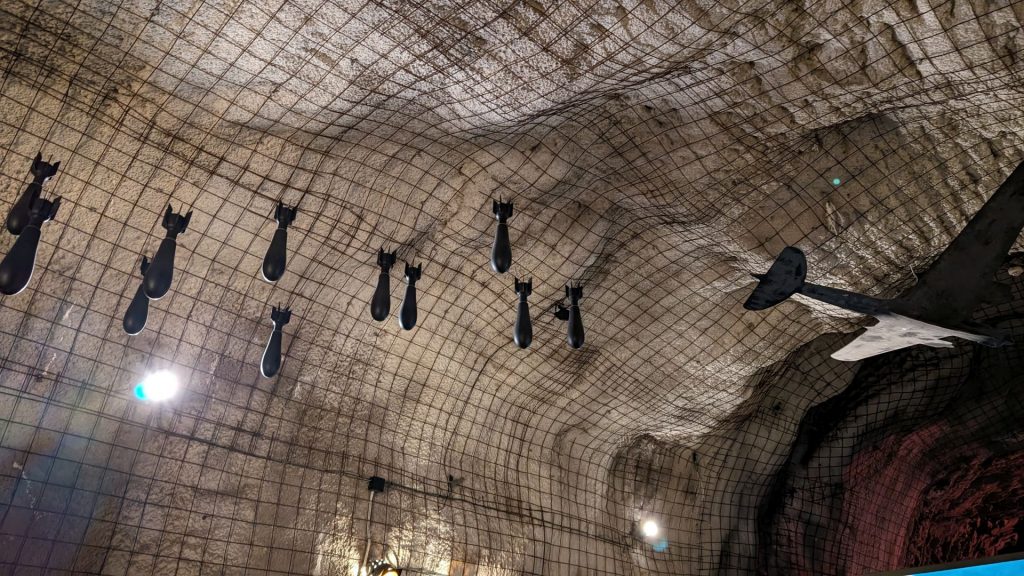

We visited the Spanish Civil War Museum a couple of days later. The museum is situated in a tunnel built on the slope of Concepción hill. This tunnel was one of the many air-raid shelters constructed in the city during the civil war, as a response to the bombings from the rebel side. Built in 2001, the museum gives an insight into the daily lives of the people who lived through this period, and how they survived.

The Spanish Civil War was between the Republicans and the Nationalists. Republicans, supported by the Soviet Union, supported the democratically elected government of Spain, while the Nationalists, supported by Nazi Germany and Mussolini’s Italy, supported the military junta that overthrew it.

The war started in 1936 when Francisco Franco and other generals launched a revolt against the democratically elected government of Spain. This revolt quickly escalated into a civil war. Franco won the war in 1939 and established a dictatorship, proclaiming himself head of state – “El Caudillo.” Franco kept a tight grip on power until his death in 1975, after which Spain made a transition to democracy.

Cartagena stayed loyal to the elected government and played a key role in the war as operations center for the Republican fleet. War materials and provisions unloaded at its docks made the defense of Madrid possible. Cartagena also became an important center of war industries in the Republican zone. This made the city a key target for the Italian and German air forces serving Franco and, in consequence, one of the cities most punished by bombing.

Why so much bombing? Cartagena had built strong military defenses because it had been the center of many armed conflicts during the previous 2,000 years. That made it very difficult to attack by land and sea. Although the anti-aircraft guns forced the planes to fly at a higher altitude, which limited the accuracy of the bombings, the sky still offered the most productive line of attack. Cartagena was targeted dozens of times. The worst was called the “four-hour bombing” of November 25, 1936, when a rain of 250-kilo devices blasted the arsenal and the train station. This was followed by hundreds of 1-kilo incendiary devices which started fires throughout the city, which caused widespread damage.

Cartagena was one of the last cities to fall to the Nationalists. It was taken by the Fourth Navarre Division on March 31, 1939.

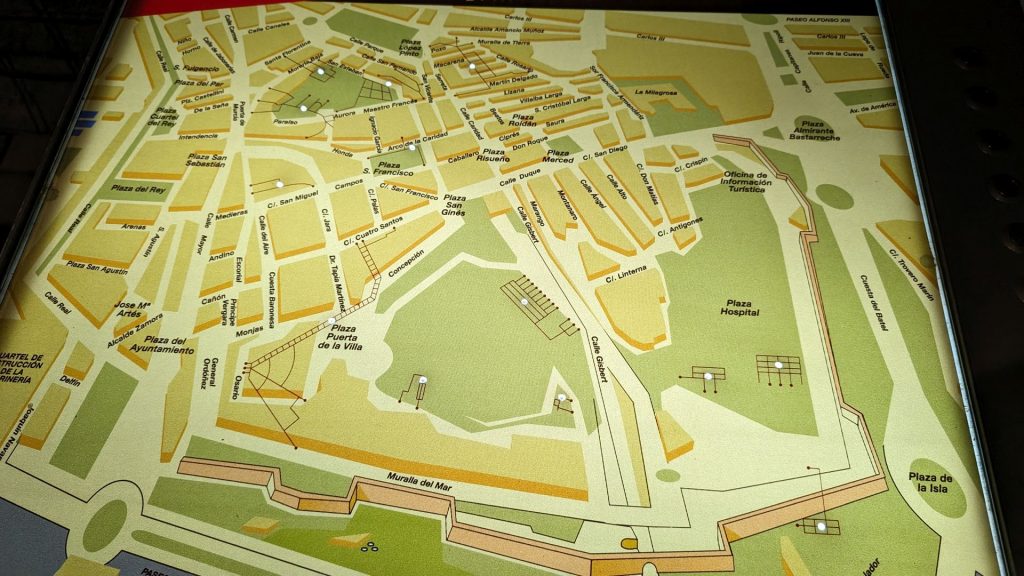

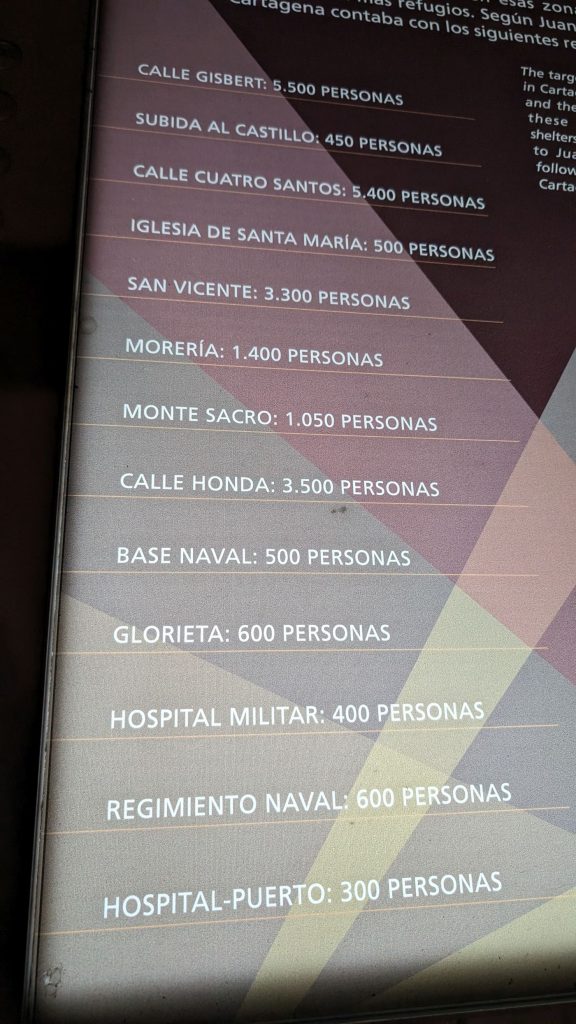

But back to the museum. The air-raid structure housing the museum – Calle Gisbert – held up to 5,500 people. Construction of the shelter began in 1937. The pictures below show the locations (white lights) and capacities of the other shelters.

The museum contains portrayals of everyday life during the civil war, types of shelters, passive defense, and active defense. Passive defense included the various ways civilians prepared themselves for the fact that they would be exposed to attacks from the air. Active defense – the Special Defense Against Aircraft (“DECA”) unit – was responsible for anti-aircraft artillery, floodlighting systems, warnings, alarms, communications, and observation.

Several stories are shared in the museum. One pertains to the Enigma machine, a rotor machine designed to encrypt and decrypt messages. It was patented in 1918. In 1926, the German Navy adopted it for military use and soon after its use spread to the other German forces. (The Enigma machine was one of the weapons that later gave the Third Reich a definitive advantage in the monumental Battle of the Atlantic in WWII.)

How does this relate to the Spanish Civil War, Cindy?

Before 1936, Spain used cipher books, which transformed information into unintelligible information. But during the Spanish Civil War, Franco determined that he would need to coordinate the offensive on different fronts and would require centralized direction. To achieve that, he asked Germany to sell 10 Enigma machines. Hitler (who supported Franco. . . but also distrusted him) did not send his most advanced models to Spain. He sent the commercial version, aimed at ensuring business communications. (The German High Command was aware of the risk it ran if any of the military versions of the machines fell into British hands.) But the commercial version still gave Franco a significant advantage.

Fast forward to 1939 and the beginning of WWII. (Yes, this is about WWII now, but also about the Enigma machine as well as the aggressive expansion of Nazi Germany, which tie back to the Spanish Civil War.) The British, with Polish scientists and intelligence services, began work on German Enigma encrypted traffic. In early 1939 the British Secret Service set up its Government Code and Cipher School in Bletchley Park, 80 km north of London.

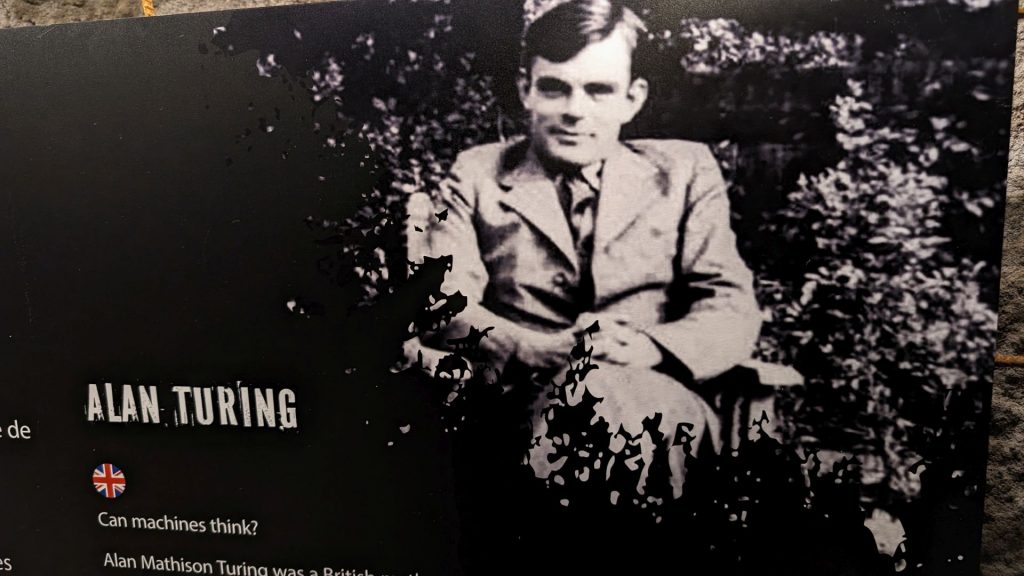

Enter Alan Mathison Turing, a British mathematician, logician, theoretical computer scientist, cryptographer, philosopher, theoretical biologist, and avid knitter. (Okay, I made up the part about knitting.) One day after Britain’s declaration of war on Germany, Alan Turing was summoned to Bletchley Park. Like all others who came to Bletchley, he was required to sign the Official Secrets Act, in which he agreed not to disclose anything about his work at Bletchley, with severe legal penalties for violating the Act. Turing created a machine (Bombe) to fight a machine (Enigma).

Aside: Turing was apparently a character. One of my favorite stories about him is that he chained his mug to the radiation pipes to prevent it from being stolen. Another favorite is that he would cycle to the office in June when he suffered from hay fever wearing a service gas mask to keep the pollen off of him.

He was also a talented long-distance runner. While working at Bletchley, Turing occasionally ran the 40 miles (64 km) to London when he was needed for meetings. He was capable of world-class marathon standards. He tried out for the 1948 British Olympic team, but he was hampered by an injury. His tryout time for the marathon was only 11 minutes slower than British silver medalist Thomas Richards’ Olympic race time of 2 hours 35 minutes.

And he was a genius! Peter Hilton (a British mathematician known for his contributions to homotopy theory* and his code-breaking during WWII) wrote this in his “Reminiscences of Bletchley Park” from A Century of Mathematics in America:

“It is a rare experience to meet an authentic genius. Those of us privileged to inhabit the world of scholarship are familiar with the intellectual stimulation furnished by talented colleagues. We can admire the ideas they share with us and are usually able to understand their source; we may even often believe that we ourselves could have created such concepts and originated such thoughts. However, the experience of sharing the intellectual life of a genius is entirely different; one realizes that one is in the presence of an intelligence, a sensibility of such profundity and originality that one is filled with wonder and excitement. Alan Turing was such a genius, and those, like myself, who had the astonishing and unexpected opportunity, created by the strange exigencies of the Second World War, to be able to count Turing as colleague and friend will never forget that experience, nor can we ever lose its immense benefit to us.”

*I looked up homotopy theory. This is the definition: “In mathematics, homotopy theory is a systematic study of situations in which maps can come with homotopies between them.”

But they used “homotopy” to describe “homotopy theory,” which seems wrong to me. So I looked up homotopy. Here is its definition: “Homotopy, in mathematics, is a way of classifying geometric regions by studying the different types of paths that can be drawn in the region. Two paths with common endpoints are called homotopic if one can be continuously deformed into the other leaving the end points fixed and remaining within its defined region.”

Back to the story: Turing created the Bombe machine. This machine was able to use logic to decipher the encrypted messages produced by the Enigma. However, it was human understanding that enabled the real breakthroughs. The Bletchley Park team made educated guesses at certain words the message would contain. For example, they knew that every day the German forces sent out a “weather report,” so an intercepted coded message would almost certainly contain the German word for “weather.” They also knew that most messages would contain the phrase “heil Hitler.” Looking for these patterns in the coded messages helped the team to calculate the daily settings on the Enigma machines. The first prototype of the Bombe was completed on March 14, 1940. Eventually, over 200 Bombes were manufactured. Alan Turing’s contribution to our current world is immeasurable. His decryption machine is the origin of all modern computing.

Tragically, Turing was prosecuted for homosexuality in 1952, then a criminal offense in the UK. He was given an option for probation, with the stipulation of chemical castration (estrogen injections). He chose this over prison. He was barred from continuing his work and lost his security clearance. Two years after his conviction, he died of cyanide poisoning.

While the official cause of Turing’s death is suicide, some believe that it may have been an accidental poisoning resulting from his experiments with cyanide in his home laboratory. Many point out that he was in good spirits. He had been promoted at his job. He suffered no demotion among his colleagues for his sexuality. The exact circumstances of his death remain a subject of interest and discussion among historians and biographers.

In 2009 (better late than never?), the UK government issued an official apology for the way Turing was treated, recognizing the impact of his persecution on his life and legacy.

Here is a picture of this genius.

What ever happened to Franco? Well, the story is too long to tell in this post. I encourage you to read about him on your own if you like history! Suffice it to say that the reviews about him are most definitely mixed.

It’s time for some more pictures of Cartagena.

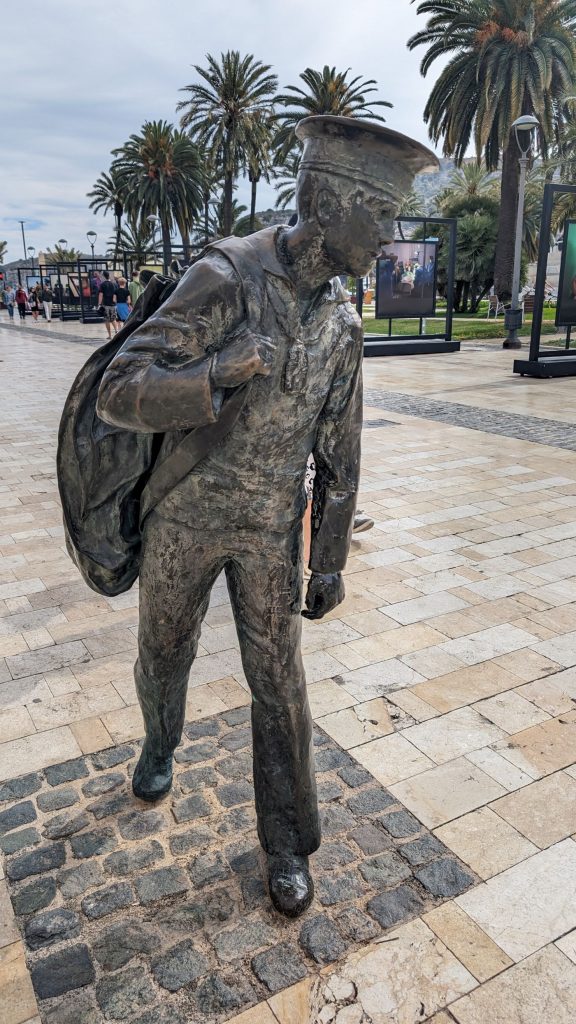

The statue pictured below is called The Replacement Sailor. It pays tribute to all those young people who, with their backpack on their shoulders, arrived in Cartagena to complete their military service.

We took Seahike out for a quick spin to see if the technicians had repaired the problem with the starboard engine (it wouldn’t rev up as much as it should) and spotted this guy!

The pictures below are of a statue called The Replacement Soldier. It is a tribute to the thousands of young people who came to Cartagena to perform their military service in the Army and more specifically to the ‘España 18’ Infantry Regiment.

Church of Santa María de Gracia

This church was built in the 18th century. There’s really not a story behind it, I just think it is pretty on the inside.

House of Fortune

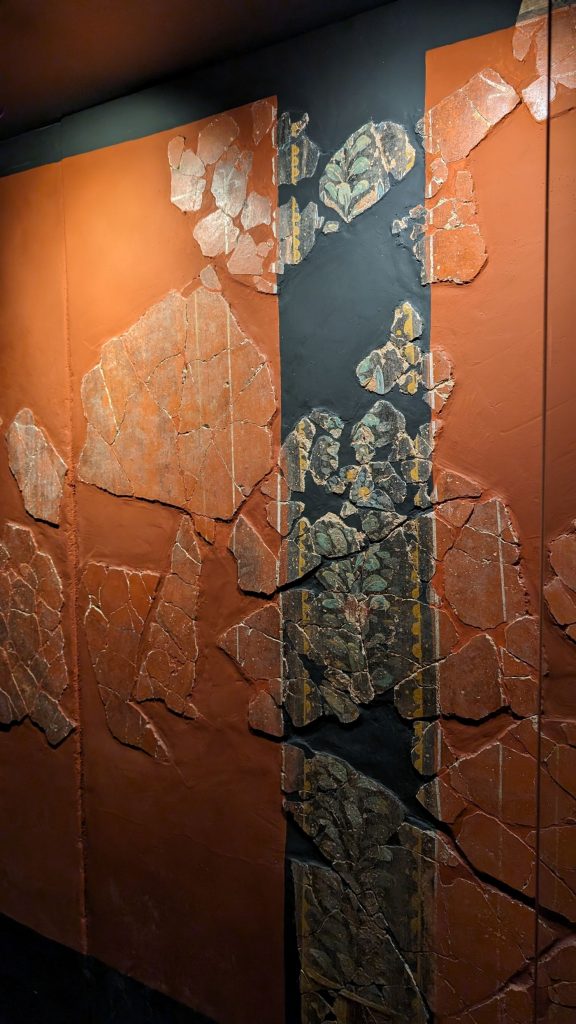

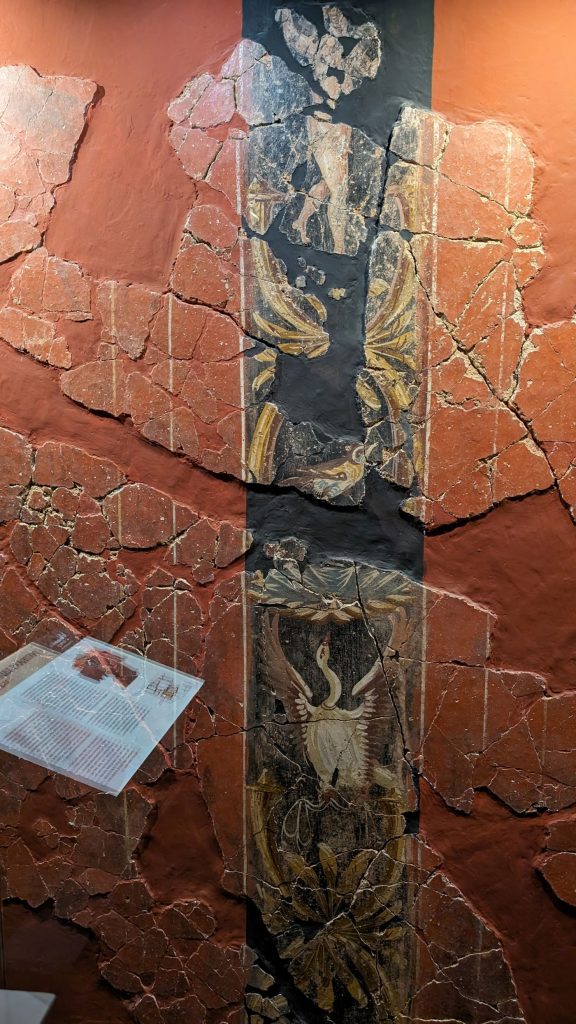

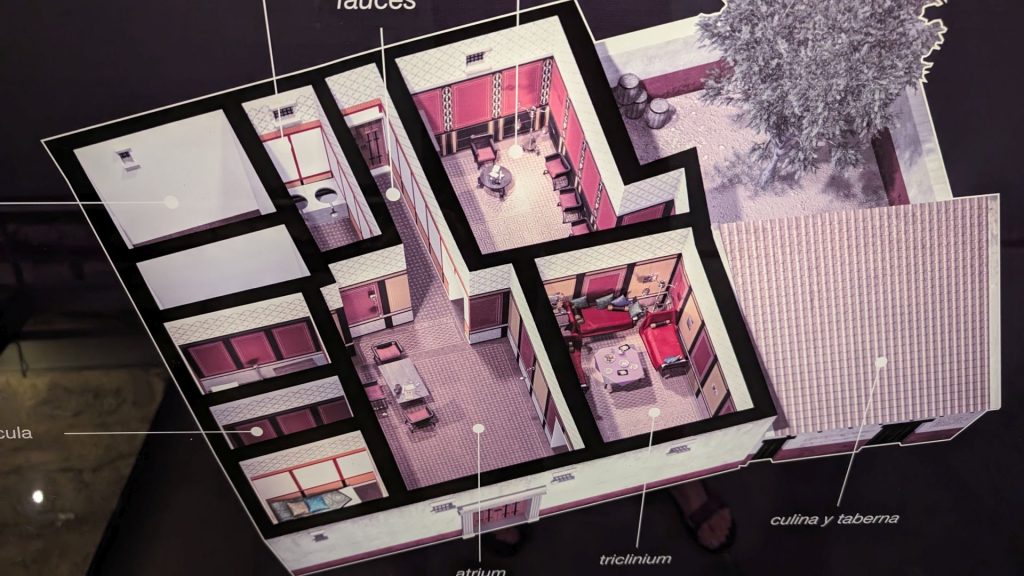

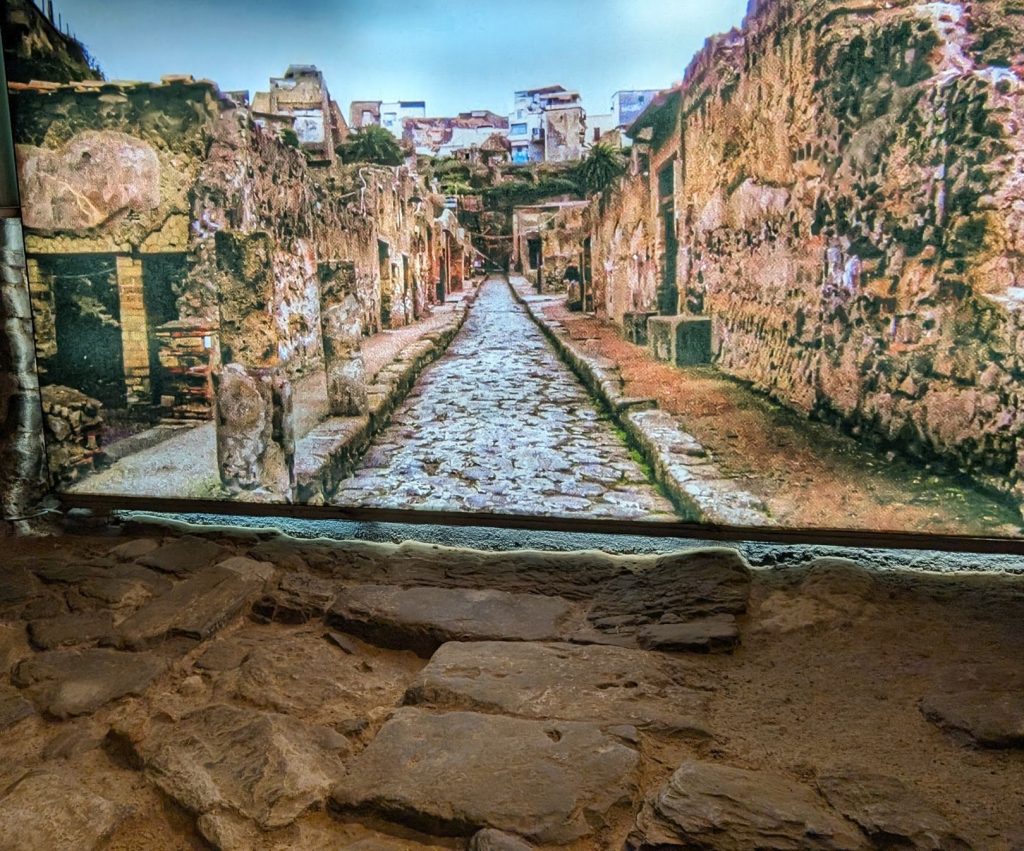

The House of Fortune is a journey back in time to the domestic life of Roman Cartagena during the 1st century AD. The site presents a well-preserved representation of the various rooms that constituted a Roman household. It occupied an area of 204 m2 and belonged to a wealthy family, since this kind of domus, a one-family house, usually was the residence of the wealthy classes. The house is adorned with murals and mosaics. The designs on these murals and mosaics include motifs like swans (which serve as the symbol of the house), fylfot crosses reminiscent of swastikas, intricate floral patterns, and pomegranates, each laden with profound mythological symbolism.

The Latin inscription “Fortuna propita” whose translation could be “Good luck,” has served to give the house its name. This welcoming greeting was displayed to be read by the people who came to the Domus by way of the back door.

The last and most colorful pictures are of the tablinum. During the excavation, many fragmented remains of paintings were found scattered on the floor. The decorative scheme included red panels separated by black panels. The highlights are the black panels, which feature figurative elements, several types of chandeliers, nude human figures that portray dancers, and birds such as the swan with outstretched wings holding a ribbon between its feet.

The paintings were made using the fresco technique. The first layer was applied to smooth out the surface. Over that layer they applied finer ones until reaching the final layer, a mixture of sand and lime, on which the paint was applied while still fresh. This allowed them to obtain a greater color consistency with a base of minerals mixed and dissolved with natural fats.