Most of the work on Seahike was done while she was on the hard. She was splashed after two weeks. Here are some pictures of Seahike and her new parts.

Our most high tech repair (the cushion covering is splitting and we haven’t been able to find a replacement):

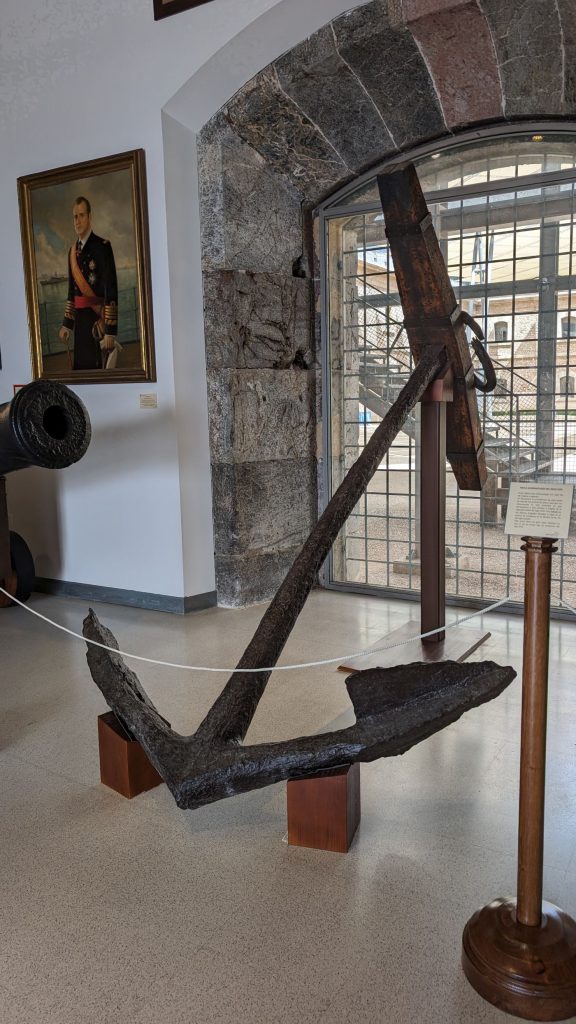

I am now going to share our visit to the Naval Museum with you. If you are completely anti-military you might want to skip the rest of this post.

I was absolutely fascinated by the naval museum! I know next to nothing about the Navy in general, and certainly nothing about the Spanish Navy. But I have learned quite a bit about sailing a small boat in the last 12+ years, which might have (it totally has!) piqued my interest in all things nautical.

Here is some of the information about the museum from their website:

The Cartagena Naval Museum has recently moved to a new location on the city’s seafront, in a privileged setting. This is a historic building from the mid-18th century, the former Prisoners and Slaves Barracks, the work of military engineer Mateo Vodopich.

The Cartagena Naval Museum houses collections of different types and nature, linked to different fields and disciplines of naval history: shipbuilding and arsenals, nautical sciences, artillery, mine warfare, health, uniforms and flags, music, painting, submarines, diving, history of the building and aspects related to the Navy today.

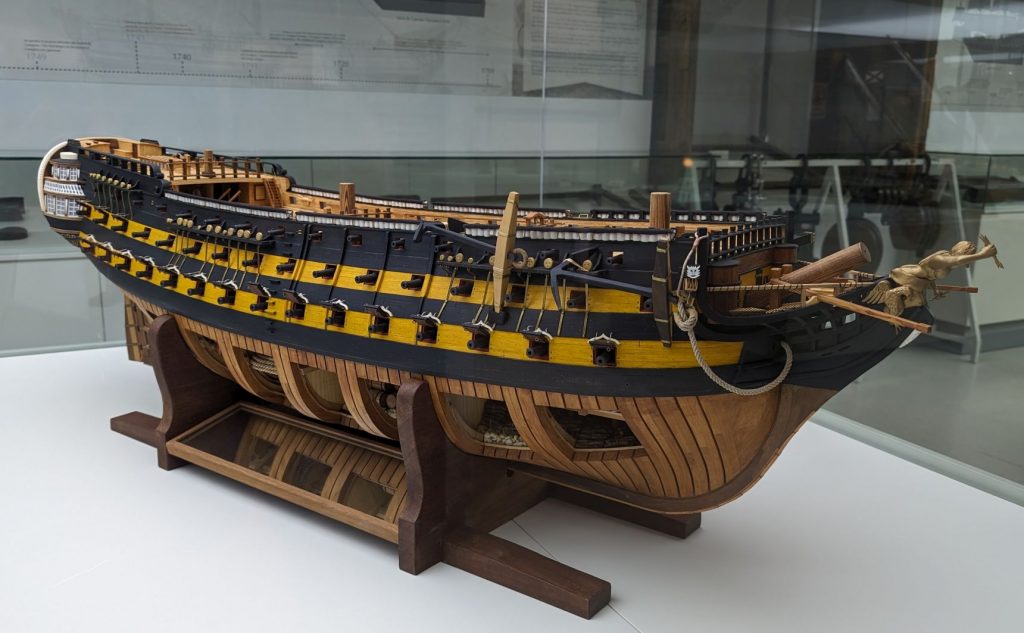

The valuable legacy of naval lieutenant Isaac Peral stands out, as well as the magnificent model of the Septentrión ship, from the 18th century.

Picture time!

Some uniforms:

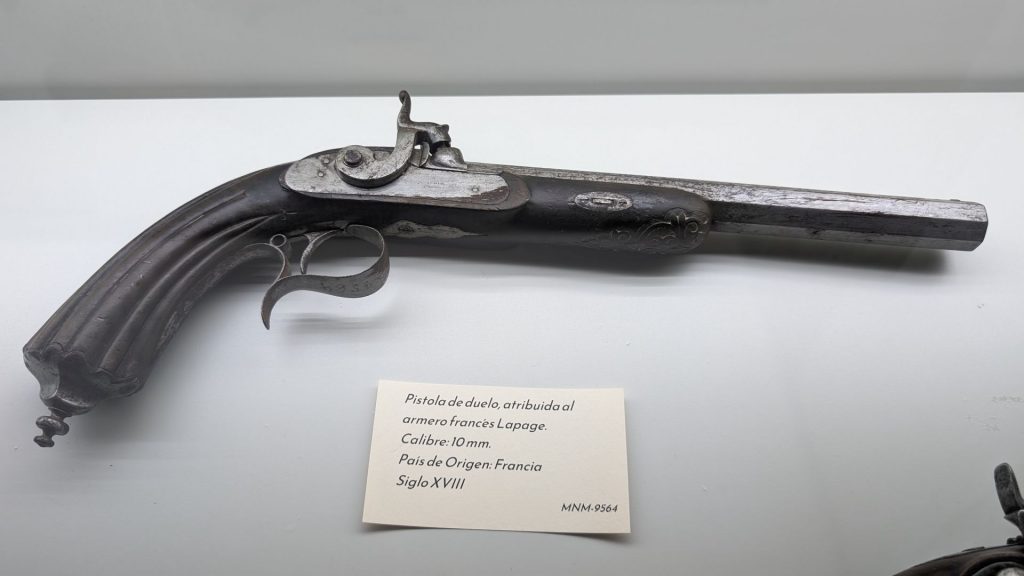

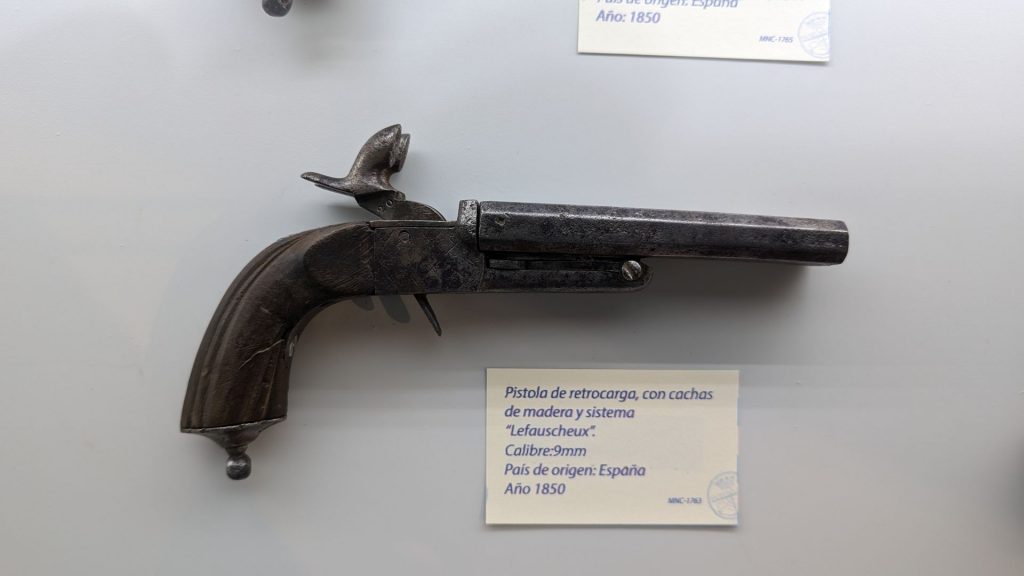

Below are two examples of the many guns on display. The one on the left is a 10 mm caliber dueling pistol, attributed to the French gunsmith Lapage. It is from the XVIII century. The one on the right is a 9 mm breech-loading pistol with wooden grips and “Lefaucheux” system. Year: 1850.

The “Lefaucheux” system refers to Casimir Lefaucheux, a French gunsmith. He is credited with the development – in 1835 – of one of the first efficient self-contained cartridge systems. The Lefaucheux cartridge had a conical bullet, a cardboard powder tube, and a copper base that incorporated a primer pellet. Lefaucheux thus proposed one of the first practical breech-loading weapons. A breechloader is a firearm in which the user loads the ammunition from the breech end of the barrel (i.e., from the rearward, open end of the gun’s barrel), as opposed to a muzzleloader, in which the user loads the ammunition from the (muzzle) end of the barrel. The vast majority of modern firearms are generally breech-loaders, while firearms made before the mid-19th century were mostly smoothbore muzzle-loaders.]

Munitions from the 1970’s:

Spanish flags and coat of arms:

Early examples of tools used for navigating, predicting weather and tides, charting, etc.

A “binnacle compass with clinometer” is also known as an inclinometer. In the marine industry, inclinometers are used mainly on ships and oil rigs to measure how much a vessel slants while being on still water and when the water is choppy.

I think these next two brass instruments are really interesting! The one on the left is a Negretti & Zambra minimum tide gauge. It recorded the height of the surrounding water area for navigation safety and other purposes.

The one on the right is an astrolabe. Astrolabes were used for making astronomical measurements and for navigation. Astrolabes were the most popular astronomical instrument for several centuries, but they eventually were replaced by quadrants, which today have been replaced by sextants.

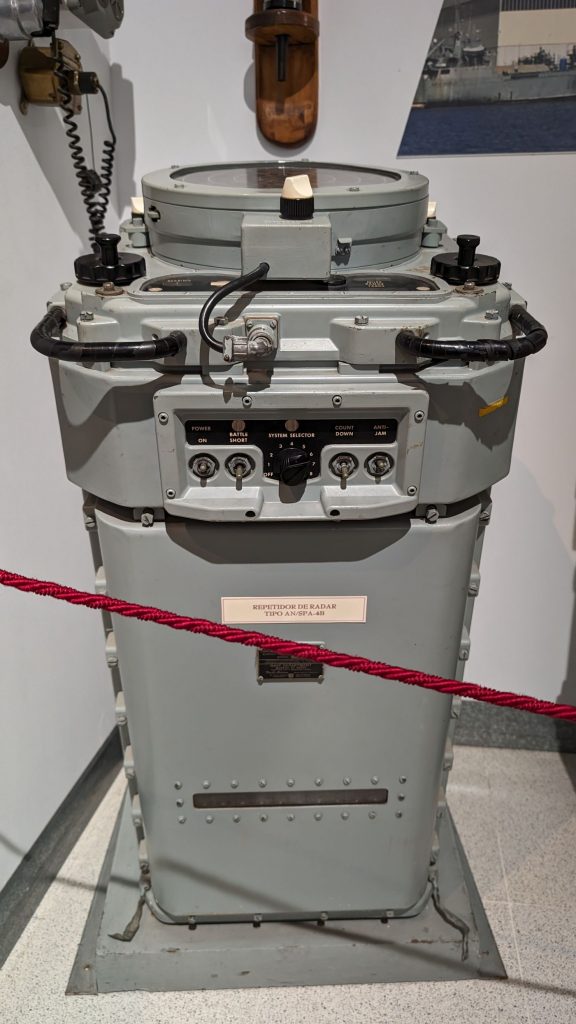

I think I’ve seen this big gray guy (below) in the movies, but not in person. It is a Type Range Azimuth Indicator AN/SPA-4B radar repeater. The purpose of a radar indicator (repeater) is to analyze radar system echo return video and to display that information at various remote locations. This indicator was capable of receiving radar information from one of eight different radar systems as selected by a front panel control. The AN/SPA-4 determined the azimuth by means of a mechanical cursor coupled to an electronic cursor; jointly they were accurate to within one degree. The SPA-4 also had the capability of transmitting electrically, the bearing and range information, to other systems such as fire control or directly to a projector on the plot table. That would cut down on verbal communication.

The brass instrument below is an Engine order telegraph (EOT). It was used to transmit orders from the command bridge to the engine room with instructions about speed and direction. It was mounted on the ship “Guadalete” from 1971 to 1998.

Pictured below: The gray piece of equipment with the handle at 180 degrees is described as the remote control of the Kamewa. Command bridge of the tugboat “Cartagena.” I am pretty sure it’s not a remote control as we think of one. I think it just meant communication from farther away.

The instrument on the right is another EOT, used to send a signal from the bridge to the engine room with instructions about speed and direction (ahead or astern). I found an image of one of these with the instructions written in English. The commands include things such as: half, full, stand by, slow, dead slow, stop.

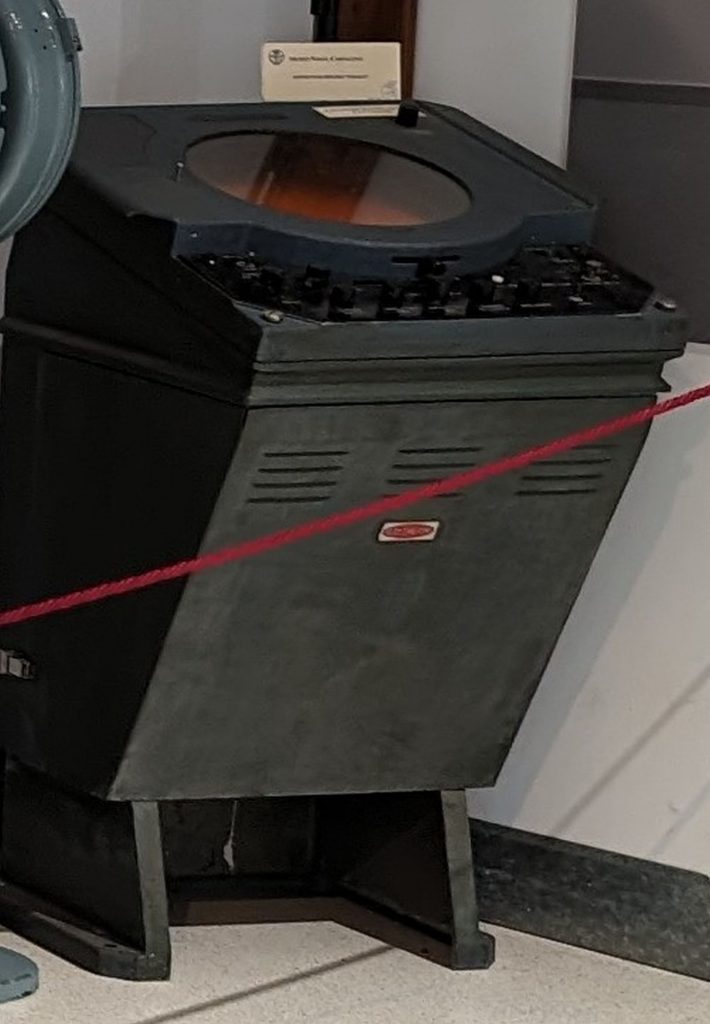

I forgot to find out what the next two things are, but the black one totally looks like a droid from Star Wars. 😉

Let’s fast forward through some model ships.

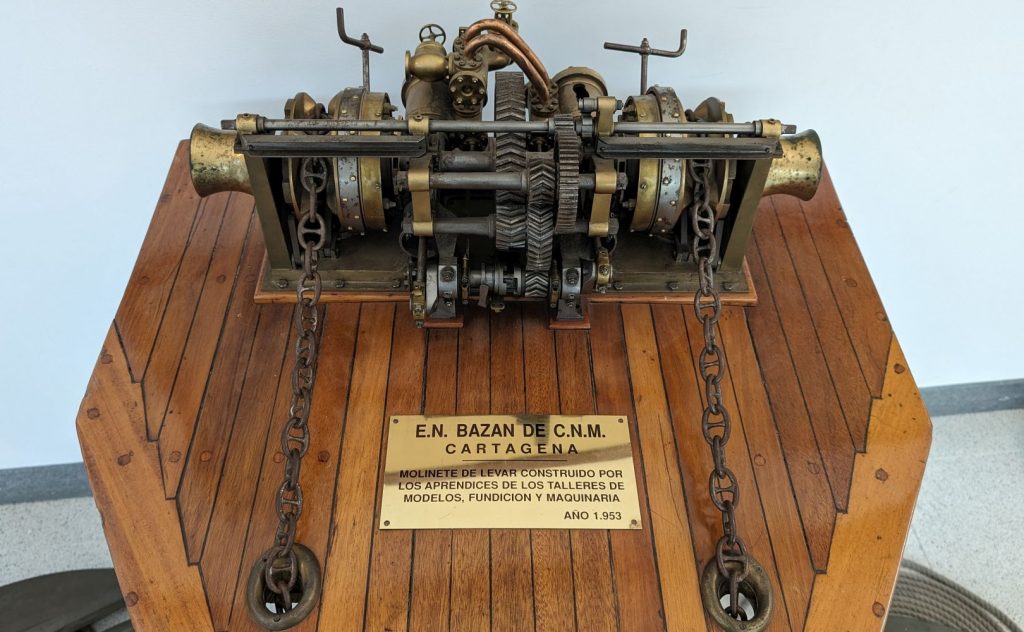

The contraption below is a windlass (used to drop and raise the anchors). It is quite different from the one on Seahike (also, we have one anchor, not two).

Let’s move to the underwater portion of the museum. Diving, submarines, mines, etc.

In 1787 the first diving schools in Spain were established, considered to be the oldest in the world. In 1846 the first diving suits arrived, in which respiration depended upon a continuous flow of air provided by a pump on the surface. On the request of García de los Reyes, the Diving School of Cartagena was created in 1922. After its reorganization in 1959, the Centre of Diving Instruction was established in the Arsenal, whose equipment adopted the novel system of autonomous diving invented by Cousteau and Gagnan.

Let’s talk about mines. My most recent “experience” with mines was when we were dissuaded from sailing in the Black Sea. . . due to mines. They are still there as of July 2024, as I write this.

I learned how to deploy a mine. Always good to know.

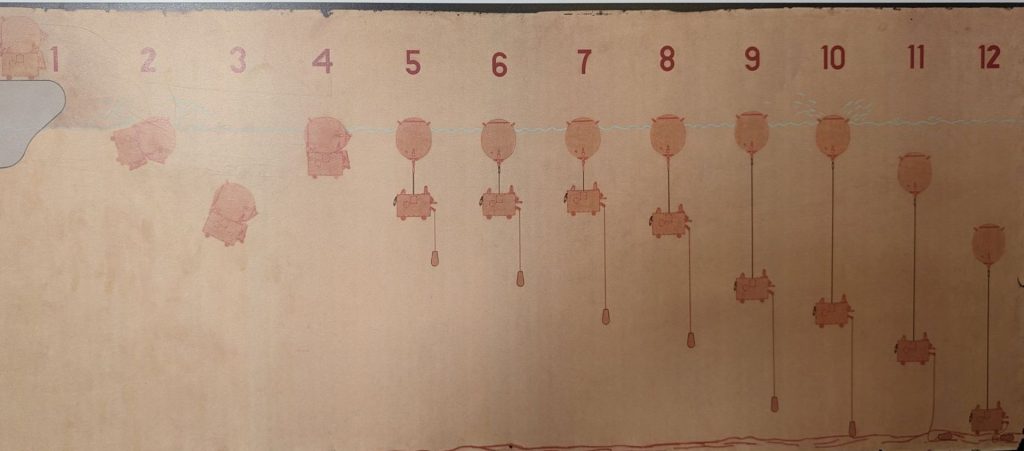

This chart shows how to deploy a mine, or should I say, how it used to be done (this is a museum, so I don’t know if/how it has changed).

Steps:

The mine is joined to a sinker and dropped in the water (Steps 1-3). The sinker returns to the surface (Step 4), floods, then separates from the mine (Step 5). At this moment, the lead also breaks away and releases a length of cable previously adjusted to the distance at which the mine should remain from the surface (Step 6). The sinker releases the cable from a reel as it sinks rapidly to the seabed so that the cable doesn’t become tangled (Steps 7-9). When the lead touches the seabed it mechanically locks the reel; sinker and mine form one unit, and when the former reaches the seabed, it drags the latter until it remains the same distance from the surface as the length of the cable lead (Steps 10-12).

Shortly afterwards, sufficient time for the minelayer to have traveled far enough away as to be out of danger, a safety catch ceases to work and the mine becomes active and ready to detonate when touched by any vessel.

Let’s move on to submarines. The Naval Museum has on display the Peral, a Spanish submarine built by naval engineer Isaac Peral. The Peral is considered the world’s first successful and successfully launched submarine.

Peral was the first to build a submarine that was powered by electricity and incorporated underwater torpedo-firing facilities. The submarine was powered by electric motors supplied by a large battery consisting of over 600 cells. These motors could propel the submarine to a speed of over three knots while submerged. Thanks to its good design and well-thought-out propulsion system, the Peral submarine could compete with the first submarines of WWI in terms of underwater speed. The submarine also featured an exceptionally modern and innovative chemical air purification system for its time, allowing the submarine to remain submerged for much longer than originally anticipated. It was armed with three torpedoes. Two of them were attached to the sides of the submarine, secured to it by cranes, while one was housed inside the hull, resting in a special launching tube.

The Peral submarine was successfully launched in September 1888, just over a year after Isaac Peral completed his plans and set them in motion. It was an historic moment, making Peral famous.

Despite the Peral’s success in all the tests proposed, in September 1890 the Board of Evaluation inexplicably issued a critical report. They said that the velocity of the submarine was not as great as expected. This was likely due in part due to one significant drawback of the Peral submarine: its lack of an onboard internal combustion engine to recharge the batteries when needed, which limited its operational range.

Both Isaac Peral and his submarine faced a series of challenges including hurdles and time-wasting measures introduced by the new Minister of the Navy José María Beránger, who wanted to derail the project. It is believed that the project did not progress due to the jealousy it aroused (the Minister wanted an award to go to his son, not to Peral). In any event, the project was halted.

I will close the story of the Peral submarine with this:

US Admiral George Dewey once said, “If Spain had used even one submarine like those invented by Peral, I would not have been able to sustain the blockade for even 24 hours.” This was in reference to the 1898 war between Spain and the United States. The “Peral Submarine” was one of the greatest achievements in the history of global navigation: the creation of an underwater vessel powered by electricity.

The destructive power of naval submarine vessels became evident during both world wars. Their devastating effects were seen not only on warships, but also the blockage of marine supply routes, as merchant shipping was one of their main targets.

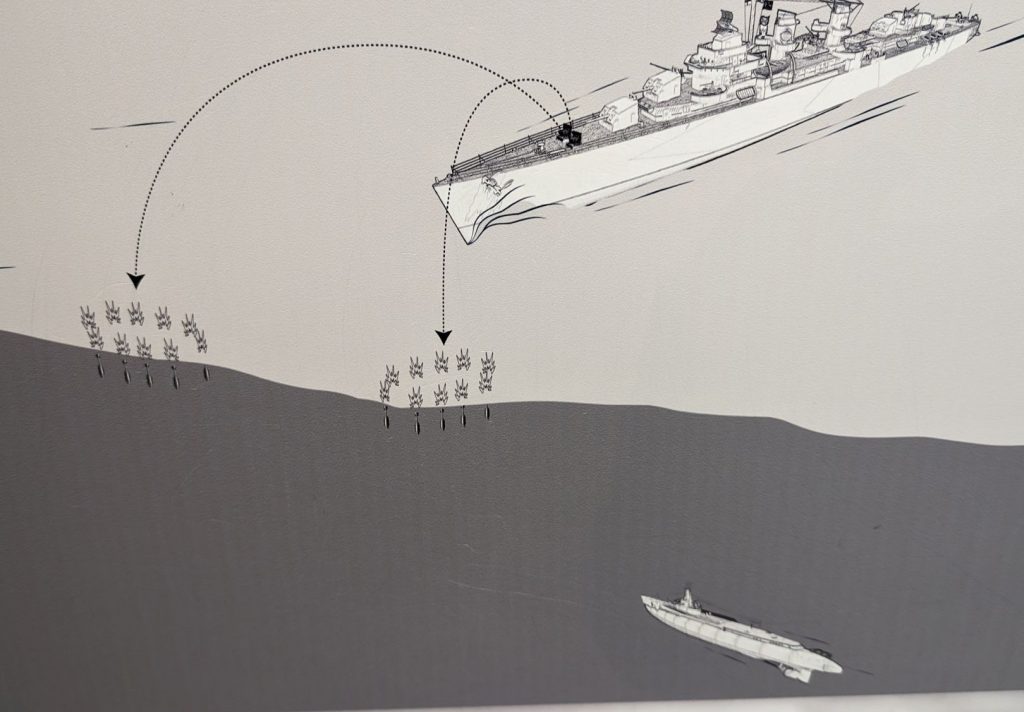

Anti-submarine warfare was the response to the threat. The anti-submarine projector known as “The Hedgehog” was developed by the Royal Navy to counterbalance attacks from German submarines during WWII. Combining depth charges and sonar, which was capable of detecting the presence of submarines through sound, it became a highly effective weapon.

The Hedgehog was mounted on the deck of escort ships, facing forward. The 24 charges launched from the vessel spread themselves out in a specific area of the sea, in circular or elliptical formation, and only exploded on contact. The Hedgehog was subsequently replaced by more advanced anti-submarine weapons, such as “Bofors” submarine rocket launchers, and acoustic torpedoes.

That’s a wrap on today’s post! Join us in our next post, when we go to Gibraltar!